TechCrunch

TechCrunch

In the latest development, Kuda, a startup out of Nigeria that operates a popular mobile-first challenger bank for consumers and (soon) small businesses, is announcing that it has raised $10 million — the biggest seed round ever to be raised in Africa. The funding comes on the back of strong demand for its services and its ambitions — according CEO Babs Ogundeyi — to become the go-to bank not just for those living on the continent, but for the African diaspora.

“We want to bank every African on the planet, wherever you are in the world,” he said in an interview. It’s starting first in its home market: since launching in September 2019, it has picked up around 300,000 customers — first consumers and now also small businesses — and on average processes over $500 million of transactions each month.

The $10 million is being led by Target Global, the giant VC out of Europe, with Entrée Capital and SBI Investment (once part of SoftBank, now no longer) also participating, along with a number of other notable individual fintech founders and angels.

The list includes Raffael Johnen (founder of Auxmoney), Johan Lorenzen (founder of Holvi), Brandon Krieg/Ed Robinson (founders of Stash), and Oliver and Lish Jung (angel investors in Nubank, Revolut, and Chime).

Prior to this Kuda — which is co-founded by Ogundeyi and CTO Musty Mustapha — had raised $1.6 million in a pre-seed round to launch a beta of its service, and Ogundeyi said he’s already working on a much bigger Series A. No valuation is currently being disclosed.

In a year where many have been watching the world economy with some trepidation on the back of a raging health pandemic hitting multiple geographies, fintech in Africa has been in the spotlight of late.

Most recently, Paystack — a payments startup out of Nigeria — got acquired by Stripe for over $200 million, making it not only Stripe’s biggest acquisition, but the largest exit-by-acquisition to-date for any Nigerian startup. That news followed closely on the heels of Interswitch, another payments startup, hitting a $1 billion valuation on the back of an investment from Visa.

But in truth, startups focused around the business of financial transactions — which also includes the adjacent industry of e-commerce (See: Jumia, the first venture-backed startup out of the region to go public) have been some of the most eagerly-watched, and their services mostly widely-adopted, of all tech plays in the region.

The reason is logical. As a contintent, Africa is one of the most populous, yet one of the more underdeveloped economically, continents in the world. And in our modern times, digital inclusion has become synonymous with financial inclusion. So, as the population begins to adopt mobile technology in earnest, those users represent a big opportunity: there is pent-up demand, and competition is relatively sparse.

That has meant a number of efforts, leveraging the growth in mobile phone usage to provide services to people to make transactions beyond those that they would otherwise only do in person, using cash. These have included innovative services like Mpesa, which uses a person’s phone (which can be a basic feature phone) as a proxy for a bank account, allowing people to pay in and pay out using their phone numbers and prepay accounts.

Nigeria — currently the biggest single economy in Africa — has also been at the center of a lot of fintech activity, and Kuda has been taking that opportunity by the horns.

In its case, that has started with building Kuda’s footprint from the ground up.

The rise of the challenger bank has been one of the more interesting developments in the world of consumer fintech, with companies like N26, Monzo, Starling, Chime, NuBank and Revolut finding a lot of traction with younger users.

But unlike many of these, Kuda does not partner with other banks to manage and back deposits with the challenger bank to in turn focus on customer service, and building user-friendly experiences and value-added services around money management. Instead, Kuda has obtained a microfinance banking license from the central bank of Nigeria.

This means that it manages payments, transfers, issues debit cards (in partnership with Visa and Mastercard). It also, he said, has partnerships with the incumbent banks Zenith Bank, Guaranteed Trust and Access Bank for people to come in for physical deposits and withdrawals when needed.

“We have built the core banking services in-house so we own the full stack,” he said. “It means we don’t have to piggy back on another financial institution. We may choose to partner on certain products but we don’t have to.” He added that the plan will be to get full licenses “in what we consider key regions” but possibly partner in others where the existing infrastructure makes it more logical to do so.

“The reason for the full license is because of monetization,” he added. “As a bank you need to be able to lend, and in Nigeria if you don’t have a full license it’s hard to lend and make money.”

Having an account is free, and so Kuda makes money through other services. Among them, users can top up their phones directly from the Kuda app (most accounts are prepaid), so Kuda acts as a kind of broker in that transaction and makes a percentage from it.

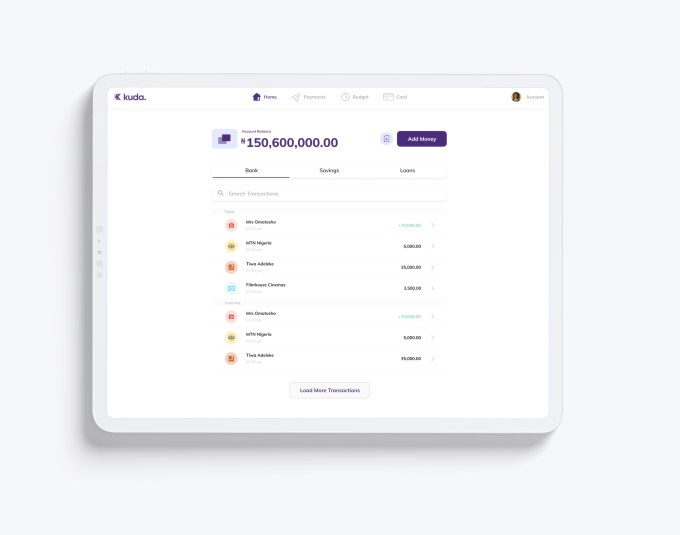

Image Credits: Kuda (opens in a new window)

Users can also pay bill through the app, where Kuda also makes a percentage. And, like other banks, Kuda manages its float and invests it in treasury bills, mutual funds and soon other credit products. There are also fees collected from debit transactions but these are not the real focus, he said.

Kuda’s mobile-first interface is not unlike a lot of the new wave of banking services built around apps, including an aim to be more than just a “dumb box” for storing money.

In its case, Kuda uses machine learning to personalize every customer, Ogundeyi said, generating suggested budgets and savings plans for its users. “The plan for our credit service is that we will base how much we issue and at what terms based on your existing spending habits,” he said.

That focus on spending dovetails with the kind of customers that Kuda is targeting. Some 70% of Nigerians are under the age of 30, and they are “smart and entrepreneurial” said Ogundeyi.

Although a pared-down version of Kuda is available for feature devices — it lacks the AI-based money management features, for one thing — the startup is mainly targeting the segment of the population that is buying and using smartphones, have the kind of incomes and lifestyles that mean they are actively depositing and spending money, and — in an increasing number of cases — also running their own businesses. That overlap means that “targeting small business owners doesn’t deviate from our original business model of younger consumers too much,” he said.

While some users are already running some of their small business banking through Kuda, a more formal small business product, with more features tailored for those users, will be launched by Q1 2021, he said.

Nigerian potential, African promise

Ogundeyi said that despite the uncertainty many are feeling around the pandemic, the relative success of Kuda and the optimism around the future of challenger banks, helped the company close this seed round (and raise other money soon) relatively easily.

“The emergence of digital challenger banks, providing customers with a free, digital and significantly better banking experience compared to services offered by traditional banks, has seen huge success across the globe,” said Dr. Ricardo Schäfer, Partner at Target Global, in a statement. “Kuda is one of Africa’s leading digital challenger banks and one of the fastest growing fintechs on the continent. We are very excited to be working with Babs, Musty and the entire Kuda team to further build on the fantastic momentum they have had since inception and support them in taking the company to the next level.” He is joining Kuda’s board with this round.

“Kuda’s relentless drive and ability to execute quickly has allowed it to carve out a highly disruptive business model in the finance and banking industry,” added Avi Eyal, partner at Entrée Capital.

Funding for any startup from the continent is rare enough that stories around it must also be viewed in the context of the bigger challenges in general that African startups have with raising money in a global market, which seems to generally be heavily biased towards developed economies (and startups in specific regions like Silicon Valley) and more known-quantity founders (which often tends to skew to while males).

“Ultimately I think there is work to be done on both sides,” he said of investors, founders and the situation of building stronger African ecosystems. “On the side of investors, more of them need to appreciate the value of the continent. And from the entrepreneurial side, there is work to be done in understanding how investors invest to get them over the line.”

He thinks that having more investors from the continent itself could help.

“Unfortunately we don’t have many African investors. My belief is that people with money typically will give money to people they understand and connect with. It’s not a surprise that if you have gone through a certain establishment (work or school) it’s easier to get funding from someone who was in that organization,” he said. “My first investment came from a friend who was at school with me.”

Indeed, Ogundeyi knows something about the workings of capital from his own first-hand experience. He was actually born England to Nigerian parents, who eventually moved back to Nigeria but kept him in the UK going to British boarding schools and eventually university. Ogundeyi still splits his time between Lagos and London (which is where he was when we spoke last week). He says that he considers himself Nigerian first.

“Nigeria has the potential to be a great national economy if it’s well harnessed,” he said. “Tech is contributing significantly to that. That is why there is a lot of interest and why we are excited to be there.”

]]>