TechCrunch

TechCrunch

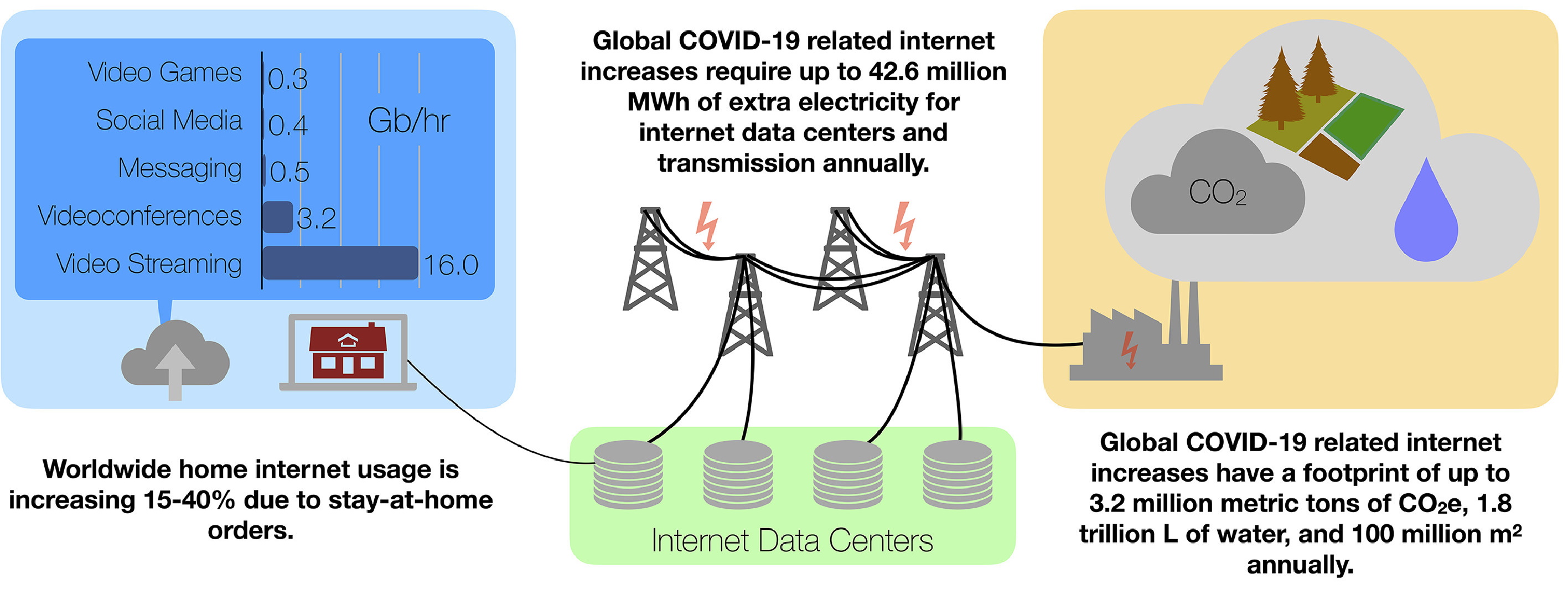

The researchers, from Perdue, Yale, and MIT, attempted to analyze the carbon, land, and water costs of internet infrastructure.

“In order to build a sustainable digital world, it is imperative to carefully assess the environmental footprints of the Internet and identify the individual and collective actions that most affect its growth,” they write in the paper’s introduction.

Using a single metric is too reductive, they argue: carbon emissions are a useful metric, but it’s also important to track the sources of the power, the water cost (derived from what’s needed to cool and operate datacenters), and the theoretical “land cost” needed to produce the product. If it sounds a little hand-wavy, that’s because any estimate along these lines is.

“In any calculation of this type at this global scale, you need to make a lot of assumptions and a lot of the data that you need are missing,” said lead study author, Yale’s Kaveh Madani, in an email to TechCrunch. “But it is a good start and best we could do using the available data.” (Madani noted that a lack of transparency in the industry, rather than a lack of statistical and scientific rigor, is the greater hindrance to the study’s accuracy.)

An example of their findings is that an hour of HD video streaming produces up to 440 grams of Carbon Dioxide emissions — up to 1,000g for YouTube or 160g for Zoom and video conferencing due differing video quality. For comparison, the EPA says a modern car produces 8,887 grams per gallon of gas. If you’re taking an hour of video meetings a day instead of commuting 20 miles to work, you’re definitely in the green, as it were, by an order of magnitude or more.

But no one is arguing that the work from home shift or increase in digital consumption is a bad thing. “Of course, a virtual meeting is better for the environment than driving to a meeting location, but we can still do better,” said Madani.

The issue is more that we think of moving bits around as having marginal environmental cost — after all, it’s bits being flipped or sent along fiber, right? Yes, but it’s also powered by enormous datacenters, transmission infrastructure, and of course the wasteful eternal cycle of replacing our devices — though that last one doesn’t figure into the paper’s estimates.

If we don’t know the costs of our choices, we can’t make them in an informed way, the researchers warn.

“Banking systems tell you the positive environmental impact of going paperless, but no one tells you the benefit of turning off your camera or reducing your streaming quality. So without your consent, these platforms are increasing your environmental footprint,” Madani said in a Perdue news release.

Leaving your camera off for a call you don’t need to be visible for makes for a small — but not trivial — savings in carbon emissions. Similarly, lowering the quality on your streaming show from HD to SD could save almost 90 percent of the energy used to transmit it (though of course your TV and speakers won’t draw any less power).

That doomscrolling habit, already a problem, seems even worse when you think that every flick of the thumb indirectly leads to a puff of hot, gross air out of a datacenter somewhere and a slight uptick in the air conditioning bill. Social media in general doesn’t use as much data as HD streaming, but the rise of video-focused networks like TikTok means they could soon catch up.

Madani explained that, puff pieces writing misleading summaries of their research aside, the study does not prescribe any simple remedies like turning off your camera. Sure, you can and should, he argues, but the change we should be looking for is systemic, not individual. What are the chances millions of people will independently and regularly decide to turn off their cameras or lower the streaming quality from 4K to 720p? Pretty low.

But on the other hand, if the costs of these services are made clear, as Madani and his team attempt to do in a preliminary way, perhaps pressure can be applied to the companies in question to make changes on the infrastructure side that save more energy in a day with an improved algorithm than 50 million people would with conscious decisions that they faintly resent.

“Consumers deserve to know more about what is happening. People currently don’t know what is going on when they press the Enter button on their computers. When they don’t know, we can’t expect them to change behavior,” Madani said. “[Policy makers] should step in, raise concerns about this sector, try to regulate it, force increased transparency, impose pollution taxes and develop incentive mechanisms if they do not want to see another unsustainable, uncontrollable sector in the future.”

The change to digital has created some amazing efficiencies and reduced or eliminated many wasteful practices, but in the process it has introduced new ones. That’s just how progress works — you hope the new problems are better than the old ones.

The study was published in the journal Resources, Conservation, and Recylcling.

]]>