TechCrunch

TechCrunch

The complaint, which has been filed by six MEPs and is being supported by the privacy campaign group noyb, alleges third-party trackers were dropped without proper consent and that cookie banners presented to visitors were confusing and deceptively designed.

It also alleges personal data was transferred to the U.S. without a valid legal basis, making reference to a landmark legal ruling by Europe’s top court last summer (aka Schrems II).

The European Data Protection Supervisor (EDPS), which oversees EU institutions’ compliance with data rules, confirmed receipt of the complaint and said it has begun investigating.

It also said the “litigious cookies” had been disabled following the complaints, adding that the parliament told it no user data had in fact been transferred outside the EU.

“A complaint was indeed filed by some MEPs about the European Parliament’s coronavirus testing website; the EDPS has started investigating it in accordance with Article 57(1)(e) EUDPR (GDPR for EU institutions),” an EDPS spokesman told TechCrunch. “Following this complaint, the Data Protection Office of the European Parliament informed the EDPS that the litigious cookies were now disabled on the website and confirmed that no user data was sent to outside the European Union.”

“The EDPS is currently assessing this website to ensure compliance with EUDPR requirements. EDPS findings will be communicated to the controller and complainants in due course,” it added.

MEP, Alexandra Geese, of Germany’s Greens, filed an initial complaint with the EDPS on behalf of other parliamentarians.

Two of the MEPs that have joined the complaint and are making their names public are Patrick Breyer and Mikuláš Peksa — both members of the Pirate Party, in Germany and the Czech Republic respectively.

We’ve reached out to the European Parliament and the company it used to supply the testing website for comment.

The complaint is noteworthy for a couple of reasons. Firstly because the allegations of a failure to uphold regional data protection rules look pretty embarrassing for an EU institution. Data protection may also feel especially important for “politically exposed persons like Members and staff of the European Parliament”, as noyb puts it.

Back in 2019 the European Parliament was also sanctioned by the EDPS over use of a U.S.-based digital campaign company, NationBuilder, to process citizens’ voter data ahead of the spring elections — in the regulator’s first-ever such enforcement of an EU institution.

So it’s not the first time the parliament has gotten in hot water over its attention to detail vis-à-vis third-party data processors (the parliament’s COVID-19 test registration website is being provided by a German company called Ecolog Deutschland GmbH). Once may be an oversight, twice starts to look sloppy…

Secondly, the complaint could offer a relatively quick route for a referral to the EU’s top court, the CJEU, to further clarify interpretation of Schrems II — a ruling that has implications for thousands of businesses involved in transferring personal data out of the EU — should there be a follow-on challenge to a decision by the EDPS.

“The decisions of the EDPS can be directly challenged before the Court of Justice of the EU,” noyb notes in a press release. “This means that the appeal can be brought directly to the highest court of the EU, in charge of the uniform interpretation of EU law. This is especially interesting as noyb is working on multiple other cases raising similar issues before national DPAs.”

Guidance for businesses involved in transferring data out of the EU who are trying to understand how to (or often whether they can) be compliant with data protection law, post-Schrems II, is so far limited to what EU regulators have put out.

Further interpretation by the CJEU could bring more clarifying light — and, indeed, less wiggle room for processors wanting to keep schlepping Europeans’ data over the pond legally, depending on how the cookie crumbles (if you’ll pardon the pun).

Additionally, noyb notes that the complaint asks the EDPS to prohibit transfers that violate EU law.

“Public authorities, and in particular the EU institutions, have to lead by example to comply with the law,” said Max Schrems, honorary chairman of noyb, in a statement. “This is also true when it comes to transfers of data outside of the EU. By using US providers, the European Parliament enabled the NSA to access data of its staff and its members.”

Per the complaint, concerns about third-party trackers and data transfers were initially raised to the parliament last October — after an MEP used a tracker-scanning tool to analyze the COVID-19 test-booking website and found a total of 150 third-party requests and a cookie were placed on her browser.

Specifically, the EcoCare COVID-19 testing-registration website was found to drop a cookie from the U.S.-based company Stripe, as well as including many more third-party requests from Google and Stripe.

The complaint also notes that a data protection notice on the site informed users that data on their usage generated by the use of Google Analytics is “transmitted to and stored on a Google server in the US”.

Where consent was concerned, the site was found to serve users with two different conflicting data protection notices — with one containing a (presumably copy/pasted) reference to Brussels Airport.

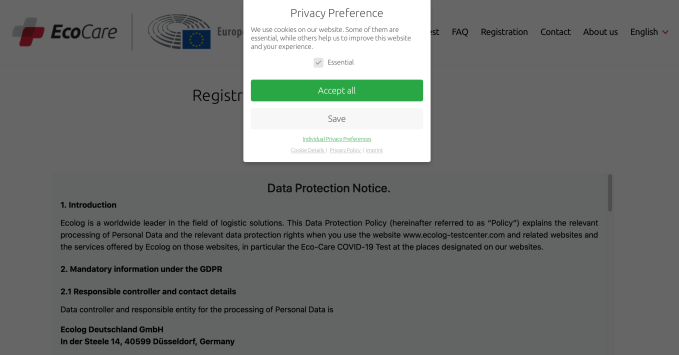

Different consent flows were also presented, depending on the user’s region, with some visitors being offered no clear opt-out button. The cookie notices were also found to contain a “dark pattern” nudge toward a bright green button to “Accept all” processing, as well as confusing wording for unclear alternatives.

A screengrab of the cookie consent prompt that the parliament’s COVID-19 test-booking website displayed at the time of writing — with still no clearly apparent opt-out for non-essential cookies (Image credit: TechCrunch)

The EU has stringent requirements for (legally) gathering consents for (non-essential) cookies and other third-party tracking technologies, which states that consent must be clearly informed, specific and freely given.

In 2019, Europe’s top court further confirmed that consent must be obtained prior to dropping non-essential trackers. (Health-related data also generally carries a higher consent-bar to process legally in the EU, although in this case the personal information relates to appointment registrations rather than special category medical data.)

The complaints allege that EU cookie consent requirements are not being met on the website.

While the presence of requests for U.S.-based services (and the reference to storing data in the U.S.) is a legal problem in light of the Schrems II judgement.

The U.S. no longer enjoys legally frictionless flows of personal data out of the EU after the CJEU torpedoed the adequacy arrangement the Commission had granted (invalidating the EU-U.S. Privacy Shield mechanism) — which in turn means transfers of data on EU peoples to U.S.-based companies are complicated.

Data controllers are responsible for assessing each such proposed transfer, on a case by case basis. A data transfer mechanism called Standard Contractual Clauses was not invalidated by the CJEU. But the court made it clear SCCs can only be used for transfers to third countries where data protection is essentially equivalent to the legal regime offered in the EU — doing so at the same time as saying the U.S. does not meet that standard.

Guidance from the European Data Protection Board in the wake of the ruling suggests that some EU-U.S. data transfers may be possible to carry in compliance with European law. Such as those that involve encrypted data with no access by the receiving U.S.-based entity.

However, the bar for compliance varies depending on the specific context and case.

Additionally, for a subset of companies that are definitely subject to U.S. surveillance law (such as Google) the compliance bar may be impossibly high — as surveillance law is the main legal sticking point for EU-U.S. transfers.

So, once again, it’s not a good look for the parliament website to have had a notice on its COVID-19 testing website that said personal data would be transferred to a Google server in the U.S. (Even if that functionality had not been activated, as seems to have been claimed.)

Another reason the complaint against the European Parliament is noteworthy is that it further highlights how much web infrastructure in use within Europe could be risking legal sanction for failing to comply with regional data protection rules. If the European Parliament can’t get it right, who is?

Indeed, noyb filed a raft of complaints against EU websites last year, which it had identified still sending data to the U.S. via Google Analytics and/or Facebook Connect integrations a short while after the Schrems II ruling. (Those complaints are being looked into by DPAs across the EU.)

Facebook’s EU data transfers are also very much on the hook here. Earlier this month the tech giant’s lead EU data regulator agreed to “swiftly resolve” a long-standing complaint over its transfers.

Schrems filed that complaint all the way back in 2013. He told us he expects the case to be resolved this year, likely within around six to nine months. So a final decision should come in 2021.

He has previously suggested the only way for Facebook to fix the data transfers issue is to federate its service, storing European users’ data locally. While last year the tech giant was forced to deny it would shut its service in Europe if its lead EU regulator followed through on enforcing a preliminary order to suspend transfers (which it blocked by applying for a judicial review of the Irish DPC’s processes).

The alternative outcome Facebook has been lobbying for is some kind of a political resolution to the legal uncertainty clouding EU-U.S. data transfers. However the European Commission has warned there’s no quick fix — and reform of U.S. surveillance law is needed.

So with options for continued icing of EU data protection enforcement against U.S. tech giants melting fast in the face of bar-setting CJEU rulings and ongoing strategic litigation like this latest noyb-supported complaint, pressure is only going to keep building for pro-privacy reform of U.S. surveillance law. Not that Facebook has openly come out in support of reforming FISA yet.

]]>