TechCrunch

TechCrunch

In March, Brooklynite Jeremy Cohen achieved minor internet fame when he launched an elaborate scheme to court Tori Cignarella, a cute stranger living in a nearby building.

After spotting Cignarella across an air shaft, Cohen used drones, Venmo, texting and FaceTime to interact with his socially distanced crush. But it was on their second date when Cohen pulled out all the stops. He purchased a gigantic plastic bubble, sealed himself inside and invited his new friend to go on a touchless walk. As Cohen wrote on Instagram, “just because we have to social distance doesn’t mean we have to be socially distant.”

Cohen’s quirky, DIY approach made for fun clickbait for a few days. But it’s also a somewhat unflattering metaphor for the kinds of touch-centric entrepreneurialism that has proliferated in the age of COVID-19. From dating to banking, education to retail, the virus has pushed everyone to rethink how touch and proximity factor into daily interactions. Businesses besieged by the uncertainty of shutdown orders, partial re-openings, remote work, disease spikes and changing consumer behavior have been forced to test-drive solutions on the fly.

Amid that confusion, a few common approaches have emerged. Some are rushing to return to normalcy, adopting quick fixes at the expense of more broad-based solutions. Others are using the pandemic as an excuse to accelerate technological shifts, even those that may be unwelcome, impractical or both. Still others are enforcing guidelines selectively or not at all, tempting consumers back, in part, through the promise of “normal” (read: non-distanced and non-regulated) interactions.

Enter haptics. Investment in touch technologies had been on the rise before COVID-19, with virtual reality fueling fresh interest in haptic gloves and full-body suits, and haptics for mobile devices like wearables and smartwatches infusing the field with new resources. While it is difficult to capture the health and growth of the haptics industry with a single number, one estimate puts the global haptics market at US$12.9 billion in 2020, projected to grow to US$40.9 billion by 2027.

In addition to established players like Immersion Corporation, founded in 1993 and active working on haptics applications ranging from gaming and automotive to medical, mobile and industrial, Sony, Apple, Microsoft, Disney and Facebook each have dedicated teams working on new haptics products. Scores of startups, too, are currently bringing new hardware and software solutions to market: Ultraleap (formerly Ultrahaptics), a Bristol-based company that develops midair haptics, has secured $85 million in funding; HaptX, which makes exoskeleton force feedback gloves for use in VR and remote manipulation, has raised $19 million in funding; and Neosensory, focused on routing sound through the skin with a wrist-based wearable Buzz, has received $16 million in funds. A recent industry-wide initiative intended to make it easier to embed haptics in multimedia content suggests that we could soon see growth in this area accelerate even further.

Despite these trends, the business of touch isn’t heading in one clear direction. And with such variety in business responses, customers have responded with confusion, frustration, anxiety and defiance. More than disgruntlement, though, COVID-19 shines a light on a longstanding debate over whether the future will have more touch or less. Tensions around touch were already high, but rapid changes, Band-Aid solutions and short-term thinking are making the problems worse.

What’s needed now is a longer view: serious, systematic thinking about where we — as consumers, citizens, humans — want and need touch, and where we don’t. To get there, we need greater investment not just in technologies that sound good, but ones that will deliver on real needs for connection and safety in the days ahead.

Plexiglass is the new mask

While the mask may be the most conspicuous symbol of the COVID-19 pandemic in much of the world, the new normal has another, clearer symbol: plexiglass.

Plexiglass leads the way as our environments are retrofitted to protect against the virus. In the U.S., demand began rising sharply in March, driven first by hospitals and essential retailers like grocery stores. Traditional sectors like automotive are using much less of the stuff, but that difference is more than made up for by the boom among restaurants, retail, office buildings, airports and schools. Plexiglass is even popping up in temples of bodily experience, surrounding dancers at strip clubs, clients at massage parlors and gymgoers in fitness centers.

Like plexiglass itself, the implications for touch are stark, if invisible. Plexiglass may communicate sterility and protection — though, truth be told, it dirties often and it’s easy to get around. More to the point, it puts up a literal barrier between us.

The story of plexiglass — like that of single-use plastic, ventilation systems, hand sanitizer and ultraviolet light — underscores how mundane interventions often win the day, at least initially. It is much easier for a grocery store to install an acrylic sneezeguard between cashiers and customers than it is to adopt contactless shopping or curbside pickup. At their best, interventions like plexiglass are low-cost, effective and don’t require huge behavior changes on the part of customers. They are also largely reversible, should our post-pandemic lifestyles revert back to something more closely resembling our previous behaviors.

Besides their obvious environmental consequences, plasticized approaches can erode our relationship to touch and thereby to each other. In Brazil, for example, some nursing homes have installed “hug tunnels” to allow residents to embrace family members through a plastic barrier. Given that “when will I be able to hug my loved ones again?” is a common and heart-wrenching question these days, the reunions hug tunnels facilitate are, well, touching. But as a shadow of the real thing, they amplify our desperate need for real connection.

The same with circles on the floor in elevators or directional arrows down store aisles: In expecting us to be our best, most rational and most orderly selves, they work against cultural inclinations toward closeness. They indicate not so much a brave new future as a reluctant present. And without proper messaging about their importance as well as their temporariness, they are bound to fail.

Touch tech to the rescue

To feed our skin hunger, futurists are pushing haptic solutions — digital technologies that can replicate and simulate physical sensations. Haptics applications range from simple notification buzzes to complex whole-body systems that combine vibration, electricity and force feedback to re-create the tactile materiality of the physical world. But although the resurgence of VR has rapidly advanced the state of the art, very few of these new devices are consumer-ready (one notable exception is CuteCircuit’s Hug Shirt — released for sale earlier this year after 15+ years in development).

Haptics are typically packaged as part of other digital techs like smartphones, video game controllers, fitness trackers and smartwatches. Dedicated haptic devices remain rare and relatively expensive, though their imminent arrival is widely promoted in popular media and the popular technology press. Effective haptic devices, specially designed to communicate social and emotional touch such as stroking, would seem particularly useful to re-integrate touch into Zoom-heavy communication.

Even with well-resourced companies like Facebook, Microsoft and Disney buying in, these applications will not be hitting home offices or teleconferencing setups anytime soon. Though it would be easy to imagine, for example, a desktop-mounted system for facilitating remote handshakes, mass producing such devices would prove expensive, due in part to the pricey motors necessary to accurately synthesize touch. Using cheaper components compromises haptic fidelity, and at this point, what counts as an acceptable quality of haptic simulation remains ill-defined. We don’t have a tried and tested compression standard for haptics the way we do with audio, for instance; as Immersion Corporation’s Yeshwant Muthusamy recently argued, haptics has been held back by a problematic lack of standards.

Getting haptics right remains challenging despite more than 30 years’ worth of dedicated research in the field. There is no evidence that COVID is accelerating the development of projects already in the pipeline. The fantasy of virtual touch remains seductive, but striking the golden mean between fidelity, ergonomics and cost will continue to be a challenge that can only be met through a protracted process of marketplace trial-and-error. And while haptics retains immense potential, it isn’t a magic bullet for mending the psychological effects of physical distancing.

Curiously, one promising exception is in the replacement of touchscreens using a combination of hand-tracking and midair haptic holograms, which function as button replacements. This product from Bristol-based company Ultraleap uses an array of speakers to project tangible soundwaves into the air, which provide resistance when pressed on, effectively replicating the feeling of clicking a button.

Ultraleap recently announced that it would partner with the cinema advertising company CEN to equip lobby advertising displays found in movie theaters around the U.S. with touchless haptics aimed at allowing interaction with the screen without the risks of touching one. These displays, according to Ultraleap, “will limit the spread of germs and provide safe and natural interaction with content.”

A recent study carried out by the company found that more than 80% of respondents expressed concerns over touchscreen hygiene, prompting Ultraleap to speculate that we are reaching “the end of the [public] touchscreen era.” Rather than initiate a technological change, the pandemic has provided an opportunity to push ahead on the deployment of existing technology. Touchscreens are no longer sites of naturalistic, creative interaction, but are now spaces of contagion to be avoided. Ultraleap’s version of the future would have us touching air instead of contaminated glass.

Touch/less

The notion that touch is in crisis has been a recurring theme in psychology, backed by scores of studies that demonstrate the negative neurophysiological consequences of not getting enough touch. Babies who receive insufficient touch show higher levels of the stress hormone cortisol, which can have all kinds of negative effects on their development. In prisons, for example, being deprived of touch through restraint or solitary confinement is a punishment tantamount to torture. As technology continues to make inroads into our lives, interactions that once required proximity or touch have become mediated instead, prompting ongoing speculation about the consequences of communicating by technology rather than by touch.

The coronavirus pandemic intensifies this crisis by demanding a sudden, collective withdrawal from physical contact. The virus lays a cruel trap: the longer we’re apart, the more we crave togetherness and are willing to take dangerous risks. But giving in to the desire to touch not only exposes us and those we care about to a potentially mortal danger, it also extends the amount of time before we can resume widespread touching.

The pandemic has already revealed important lessons about touch, haptics and humanity. First is that while circumstances can change quickly, true social and behavioral change takes longer. The many examples of Americans acting as though there is no pandemic going on should give pause to anyone thinking touch-free futures are just around the corner. Atop this, there is plain-old inertia and malaise, which suggests some pandemic-era interventions will stick around while others will disappear or slacken over time. Consider 9/11 — nearly two decades later, though we still can’t greet our loved ones at their gate, most airports don’t strictly monitor our liquids and gels.

By the same token, one can imagine unfilled hand sanitizer stations as the ultimate hangover from these times. We may begin to like the plexiglass barriers between ourselves and our fellow subway passengers, but hate them at restaurants and sporting events. We may encounter more motion-detecting sliding doors and hand-tracking options, but when they falter we may revert to revolving doors, handles and push-buttons.

A second and equally important insight is that the past and the future exist side by side. Technological development takes even longer than behavioral change, and can be bedeviled by momentary trends, expense and technological limitations. For example, there are a lot of pressures right now to transform stores and restaurants into “last-mile” fulfillment centers, to embrace AR and VR and to reimagine space as contact-free. In these scenarios, objects could be touched and handled in virtual showrooms using high-fidelity digital touch technologies. But some of this pressure is based on promises that haptics have yet to fulfill. For instance, being able to touch clothing through a mobile phone may be possible in theory, but would be difficult in practice and would mean other trade-offs for mobile phones’ functionality, size, weight and speed.

Touch/more?

But just as the coronavirus pandemic did not create making us miss touching, it also did not create all the problems with touching. Some of the touch we were used to — like the forced closeness of a crowded subway car or the cramped quarters of airline seats — is dehumanizing. Social movements like #MeToo and Black Lives Matter have drawn attention to how unwanted touch can have traumatic consequences and exacerbate power imbalances. We must think broadly about the meaning of touch and its benefits and drawbacks for varying types of people, and not rush toward a one-size-fits-all solution. Although touch may seem like a fundamentally biological sense, its meaning is continually renegotiated in response to shifting cultural conditions and new technologies. COVID-19 is the most rapid upheaval in global practices of touching that we’ve seen in at least a generation, and it would be surprising not to see a corresponding adoption of technologies that could allow us to gain back some of the tactility, even from a distance, that the disease has caused us to give up.

Too often, however, touch technologies prompt a “gee whiz” curiosity without being attentive to the on-the-ground needs for users in their daily lives. Businesses looking to adopt haptic tech must see through the sales pitch and far-flung fantasies to develop a long-term plan for where touch and touch-free make the most sense. And haptic designers must move from a narrow focus on solving the complex engineering problem touch presents to addressing the sorts of technologies users might comfortably incorporate into their daily communication habits.

A useful exercise going forward is to consider how would we do haptic design differently knowing we’d be facing another COVID-19-style pandemic in 2030? What touch technologies could be advanced to satisfy some of the desires for human contact? How can firms be proactive, rather than reactive, about haptic solutions? As much as those working in the field of haptics may have been motivated by the noble intention of restoring touch to human communication, this mission has often lacked a sense of urgency. Now that COVID-19 has distanced us, the need for haptics to bridge that physical gap, however incompletely, becomes more obvious and demanding.

Businesses feel it too, as they attempt to restore “humanity” and “connection” to their customer interactions. Yet as ironic as it might feel, now is the time not to just stumble through this crisis — it’s time to prepare for the next one. Now is the time to build in resilience, flexibility and excess capacity. To do so requires asking hard questions, like: do we need VR to replicate the sensory world in high fidelity, even if it’s costly? Or would lower-cost and lower-fidelity devices suffice? Will people accept a technologized hug as a meaningful proxy for the real thing? Or, when touch is involved, is there simply no substitute for physical presence? Might the future have both more touch and less?

These are difficult questions, but the hardship, trauma and loss of COVID-19 proves they demand our best and most careful thinking. We owe it to ourselves now and in the future to be deliberate, realistic and hopeful about what touch and technology can do, and what they can’t.

]]>

TechCrunch

TechCrunch

The ADA originally applied mainly to things like buildings and government resources, but over the years (and with improvements and amendments) came to be much broader than that. As home computers, the web and eventually apps became popular, they too became subject to ADA requirements — though to what extent is still a matter under debate.

I asked a few prominent companies and advocacy organizations what they think about how tech has improved the everyday lives of people with disabilities, and where it has so far fallen short.

Those who responded had the most to say about how tech has helped, of course, but also offered suggestions (and recriminations) for an industry that has in some ways only recently begun to truly include people with disabilities in its processes — and in many ways has yet to do so.

Claire Stanley, Advocacy and Outreach Specialist at the American Council for the Blind

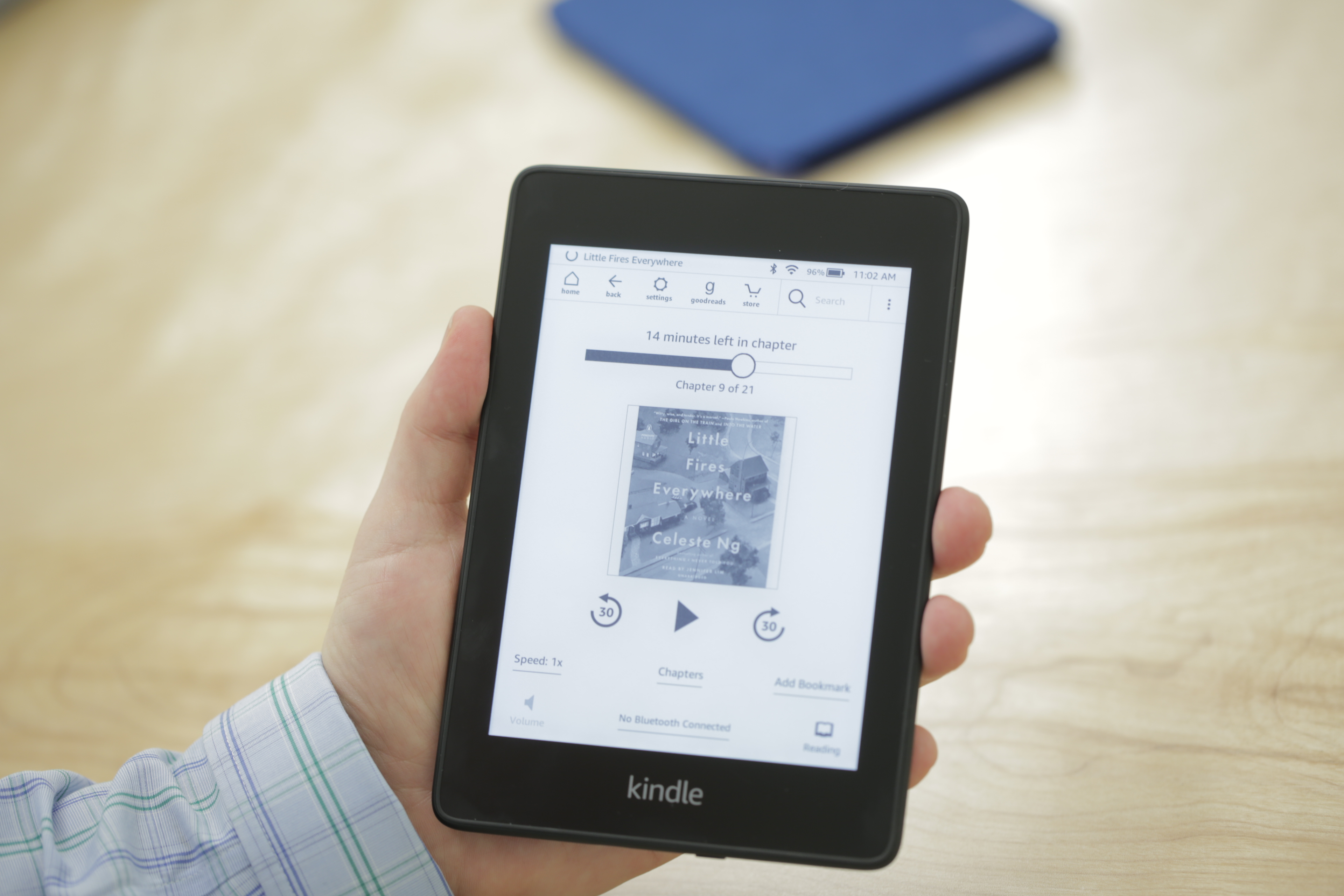

“Tech has opened the door to so many things,” said Stanley. “Books, for instance — 10 years ago to get a book you might have to wait for the Library of Congress to convert it to audio. Now, because of Kindles and e-readers, the day a book comes out I can buy it. Access is a lot faster than it once was.”

“The ability to do certain things in the workplace, too. The caveat is, people don’t always design software to work with accessibility technology. Designing with screen readers in mind can be very helpful, but if they don’t, that opens up whole new problems,” she said.

“Companies just don’t think about accessibility, so they design a product that’s totally inaccessible to screen readers. To my understanding, if you design it right from the get-go it should be easy to make it compatible. There are the WCAG standards — if programmers took even a cursory glance at these, they’d be like, ‘oh I get it!,’ ” said Stanley. “And I’ve heard from a lot of people that when you make something accessible to the blind it makes it better for everybody.”

That’s exactly the problem that Fable intends to alleviate by providing software testers with various disabilities as a service to companies that may not have thought that far ahead in their QA process.

New devices and services are also changing the landscape for blind folks.

“Braille literacy is going down because people are turning to audio synthesizers — but new designs of braille readers are coming out, and they’re getting cheaper. I have mine right next to me,” said Stanley.

Of course for the deaf-blind community braille is still indispensable. One dad hoping to teach his daughter braille recently built his own inexpensive braille education device — not something you were likely to do 20 years ago.

“And Aira is an app that has been around for about four years — basically, through video from your phone, a person on the other end can answer questions and identify things. I use it all the time. They’re starting to integrate AI to do some simple things like read signs,” Stanley said.

“We’ve also been working a lot in the autonomous vehicle space. That will open up a lot of doors, and not just for blind people, but people with other disabilities, the elderly, children,” she added. “I know we have a long way to go, but we’ve been fortunate enough to be at the table with companies and Congress when we’re talking about what making an autonomous vehicle accessible looks like.”

Eve Andersson, Director of Accessibility at Google

“To me, one of the most notable tech advances has been changes in captioning technology. About two years after I started at Google, in 2009, we introduced automatic captioning on YouTube using AI. Then eight years later, we introduced the ability to caption sound effects (laughter, music, applause, etc.) to make video content even more accessible,” said Andersson.

She pointed out that although captions were originally made with accessibility for deaf and hard of hearing users, they quickly became helpful for many other users who wanted to be able to watch videos on mute, in other languages and so on.

“Programming computers to be able to understand and display or translate language is allowing for so many more advances that benefit everyone. For example, speech recognition and voice assistants have made it possible to have the speech to text features that we have today, like voice typing in Google Docs or dictation in Chrome OS,” she said.

Live transcribe is another feature that tech has enabled, letting hearing impaired people follow in-person communications live.

“Before the ADA, some parts of the physical world remained inaccessible to people who are blind or low-vision,” Andersson said. “Today, you can find braille under almost all signs in the United States, which paved the way for us to create products like Google BrailleBack and the TalkBack braille keyboard, which both allow braille users to gain the information they need and communicate effectively with the world around them. In addition, the spirit of ADA in making the physical world accessible to people with disabilities is what inspired innovations like Lookout, an app that helps people who are blind or low-vision identify the world around them.”

“One area that we’re thinking about more and more is how to leverage technology to be more helpful for people with cognitive disabilities. This is an incredibly diverse space spanning many different needs, but it remains largely unexplored,” she said. “Action blocks” in Android are an early effort to address it, simplifying multi-step processes into single buttons. But the team is looking into larger scale improvements to help out those who have trouble using a smart device out of the box.

“As an industry, we need to work to ensure that people with disabilities — from employees to consultants to users — are always included in the process of developing a product, research area or initiative from the very beginning,” she said. “People with disabilities or who have family members with disabilities on my team bring their experiences to the table and we make better products as a result.”

Sarah Herrlinger, Director of Global Accessibility Policy at Apple

“It’s fundamentally about culture,” said Herrlinger. “From the beginning Apple has always believed accessibility is a human right and this core value is still evident in everything we design today.”

Though somewhat general of a statement, Apple has the history to back it up. The company has famously been ahead of others on the accessibility curve for decades. TechCrunch columnist Steve Aquino has documented these efforts over the years, summing many up in this feature.

The iPhone, being Apple’s flagship product since its introduction, has also been its main platform for accessibility.

“The historical impact of iPhone as a mainstream consumer product is well documented. What is less understood though is how life changing iPhone and our other products have been for disability communities,” said Herrlinger. “Over time iPhone has become the most powerful and popular assistive device ever. It broke the mold of previous thinking because it showed accessibility could in fact be seamlessly built into a device that all people can use universally.”

The feature that has been helpful to the most people is likely VoiceOver, which intelligently reads off the contents of the screen in a way that allows blind users to navigate the OS easily. One such user posted her experience recently, racking up millions of views:

As for where the tech industry has room to grow, Herrlinger said: “Representation and inclusion are critical. We believe in the mantra of many within disability communities: ‘Nothing about us without us.’ We started a dedicated accessibility team in 1985, but like all things on inclusion — accessibility should be everyone’s job at Apple.”

Melissa Malzkuhn, Founder & Creative Director, Motion Light Lab at Gallaudet University

“If not for the laws in place to safeguard our access, no one would implement them,” Malzkuhn said frankly. “The ADA really helped push greater access, but we also saw a lot of change in how people think, and what is considered socially responsible. More and more people now see that their use of social media comes with a sense of social responsibility to make their posts accessible. We would like to see that social accountability with all individuals, and with all companies, big and small.”

Gallaudet is a university that aims to be “barrier-free for deaf and hard of hearing students,” providing a huge amount of resources and instruction for that community. Many of the technologies its staff has used for years have seen major improvements as mainstream users have flocked to virtual meetings and the like and found them wanting.

“We have more video meeting options than ever, and they continue to improve. We also have seen a constant improvement in our experience with video relay services,” Malzkuhn said. She also cited voice-to-text as having improved a lot and provided serious utility; Gallaudet’s Technology Access Program has worked with Google’s Live Transcribe.

“Language-mapping processing, and the early pioneering work on gesture and sign recognition is exciting,” she added, though the latter is still a ways from practical use. She was unsparing in her criticism of the many attempts at smart gloves, however: “Enough with the sign language gloves. It reinforces a bigger ideology: Give deaf people something to wear and our communication issues will go away. It is not about putting the burden of communication on one group of people.”

“I would say that the Apple iPad has revolutionized how we look at the experience of reading for deaf children. In the Motion Light Lab here at Gallaudet University, we have created bilingual storybook apps, intersecting both ASL videos and written text on the same interface,” she said. “But technology will never replace the humanity in all of us. All it takes are attitudes and the willingness to communicate, regardless of technology. Learning a bit of sign language goes a long way.”

Malzkuhn emphasized the value of inclusion and chastised companies that fail to take even elementary steps in hiring and process.

“Companies that hire deaf people have it right. Companies that focus on inclusive design and accessibility as an important and ‘non-negotiable’ aspect in product design also have it right. Their products are invariably superior to inaccessible products,” she said, while those who do not are guilty of “a serious omission. Many companies strive to create products to ‘help’ our lives, but if we are not in the room in the first place, and if we do not have a seat at the table, that is not helpful. Inclusive design starts with an inclusive team.”

Investors need to look at startups focused on accessibility and deafness as well. Like any growing community, they need funding and mentorship.

Malzkuhn also wanted to make sure that companies are thinking about the deaf and hard of hearing not just as consumers of an end product, but full-fledged users.

“That is a driving force in my work — we need to always give tools so anyone can design technology. We need to ensure that we have the responsibility of training, teaching and making those accessible so we develop and cultivate the next generation of young deaf people who design and construct, who are architects of systems, who can program systems, as well as being end users of technology.”

Jenny Lay-Flurrie, Chief Accessibility Officer at Microsoft

“On a personal level, the ADA drove a new bar of awareness and provision of captioning, interpreting which are both invaluable to me in the workplace, home and navigating crucial life needs like medical care,” said Lay-Flurrie. “Technology can unlock solutions that can help empower people with disabilities in the spirit of the ADA and lead to greater innovations for everyone. To enable transformative change accessibility needs to be a priority.”

Like Google’s Eve Andersson, Lay-Flurrie highlighted captioning as a major recent advance.

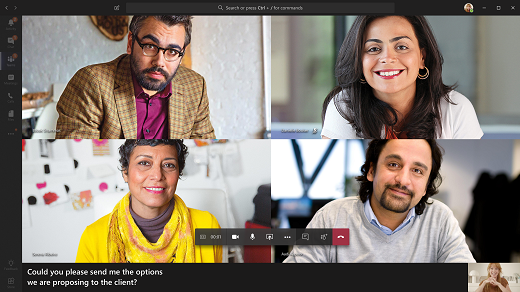

“Captioning, like many other aspects of accessibility, is increasingly woven into the fabric of what we do,” she said. “Captioning has evolved so much in the last 30 years, and accelerated as a result of AI and ML in the last five. Teams now has AI captioning integrated and we have seen the impact of that during COVID with Teams Captioning usage up 30x from a few months prior.”

“Accessibility has also diversified — with technologies like Seeing AI, Learning Tool, and the Xbox Adaptive Controller as Microsoft focuses on inclusive design, building with and for people with disabilities in these instances, creating breakthrough technologies for blind/low vision, dyslexia and mobility,” she said.

The Adaptive Controller was one of the best hardware surprises of recent years — a device for playing games and interacting with computers and consoles that’s hyper-compatible and clearly the result of immense effort and expenditure.

It’s an example of one of the “doors that remain closed and need to be opened, vehemently and with speed,” as Lay-Flurrie put it. “Seeing AI is a great lens on what is possible here, and I get excited to think about what AI/ML, as well as ARm can do across the spectrum of disability. Additionally, we believe that AI can help unlock solutions to some of the biggest challenges people with disabilities face, which is why the AI for Accessibility program plays a crucial role in how Microsoft is working to drive inclusive innovation.”

Lay-Flurrie had a good deal to say on how to integrate inclusivity into a company’s processes — and with good reason, seeing as Microsoft has been a leader on these issues for years.

“Accessibility isn’t optional. It must be part of your business, ecosystem and managed/measured,” she said. “It starts with people and we have really focused on how we build an inclusive culture, pipeline of talent. Though we are still continuing to grow and learn, we have also taken steps to share our learnings with other organizations through resources like the Autism Hiring Playbook, Accessibility at a Glance training resources, the Supported Employment Program Toolkit and the Inclusive Design Toolkit.”

“We realize that each organization has its own pace and starting point. The first step is to recognize the need to design for accessibility,” she continued. “It’s particularly important to evaluate the maturity of a product development life cycle through the lens of accessibility and look to build in assistive features from the start, not bolted on later in the process. But there is more to do here. Until then, my mantra stands — if you don’t know it’s accessible, it’s not.”

Mike Shebanek, Head of Accessibility at Facebook

“The portability, ease of use, affordability and built-in accessibility of smartphones has allowed people with disabilities to be more connected, more mobile and more independent than anyone thought possible 30 years ago,” said Shebanek. “The rise of voice technologies like speech synthesis, speech recognition and voice control of devices has also radically improved the lives of people with disabilities.”

“Facebook created React Native, and made it open source, so that developers can create accessible mobile apps. We’ve also helped set global digital standards for web accessibility that enable everyone to enjoy a more accessible internet,” he continued.

Like the others, he suggests that tech companies need to consider accessibility needs and methods early on, and increase the numbers of people with disabilities in the development and testing process.

Machine learning is helping address some major obstacles in a more automated way: “We’re using it at Facebook to power automatic video captioning and create automatic Alt-Text to provide spoken descriptions of photographs to people who are blind,” said Shebanek. “But these are only recent innovations and the industry has barely begun to scratch the service of what’s possible in the next 30 years as we begin to thoughtfully address the needs of people with disabilities.”

]]>