TechCrunch

TechCrunch

It isn’t like you’re totally clueless, right? You’re probably aware that Paul Ryan now has a SPAC, as does baseball executive Billy Beane and Silicon Valley stalwart Kevin Hartz.

You likely know, too, that brash entrepreneur Chamath Palihapitiya seemed to kick off the craze around SPACs — blank-check companies that are formed for the purpose of merging or acquiring other companies — in 2017 when he raised $600 million for a SPAC. Called Social Capital Hedosophia Holdings, it was ultimately used to take a 49% stake in the British spaceflight company Virgin Galactic.

But how do SPACs come together in the first place, how do they work exactly, and should you be thinking of launching one? We talked this week with a number of people who are right now focused on almost nothing but SPACs to get our questions — and maybe yours, too — answered.

Why are SPACs suddenly sprouting up everywhere?

Kevin Hartz — who we spoke with after his $200 million blank-check company made its stock market debut on Tuesday — said their popularity ties in part to “Sarbanes Oxley and the difficulty in taking a company public the traditional route.”

Troy Steckenrider, an operator who has partnered with Hartz on his newly public company, said the growing popularity of SPACs also ties to a “shift in the quality of the sponsor teams,” meaning that more people like Hartz are shepherding these vehicles versus “people who might not be able to raise a traditional fund historically.”

Don’t forget, too, that there are whole lot of companies that have raised tens and hundreds of millions of dollars in venture capital and whose IPO plans may have been derailed or slowed by the COVID-19 pandemic. Some need a relatively frictionless way to get out the door, and there are plenty of investors who would like to give them that push.

How does one start the process of creating a SPAC?

The process is really no different than a traditional IPO, explains Chris Weekes, a managing director in the capital markets group at the investment bank Cowen. “There’s a roadshow that will incorporate one-on-one meetings between institutional investors like hedge funds and private equity funds and the SPAC’s management team” to drum up interest in the offering.

At the end of it, institutional investors, which also right now include a lot of family offices, buy into the offering, along with a smaller percentage of retail investors.

Who can form a SPAC?

Pretty much anyone who can persuade shareholders to buy its shares.

What happens right after SPAC has raised its capital?

The money is moved into a blind trust until the management team decides which company or companies it wants to acquire. Share prices don’t really move much during this period as no investors know (or should know, at least) what the target company will be yet.

These SPACs all seem to sell their shares at $10 apiece. Why?

Easier accounting? Tradition? It’s not entirely clear, though Weekes says $10 has “always been the unit price” for SPACs and continues to be with the very occasional exception, such as with hedge fund billionaire Bill Ackman’s Pershing Square Capital Management. (Last month it launched a $4 billion SPAC that sold units for $20 each.)

Have SPACs changed structurally over the years?

They have! Years back, when a SPAC told its institutional investors (under NDA) about the company it had settled on buying, these investors would either vote ‘yes’ to the deal if they wanted to keep their money in, or ‘no’ if they wanted to redeem their shares and get out. But sometimes investors would team up and threaten to torpedo a deal if they weren’t given founder shares or other preferential treatment in what was to become the newly combined company. (“There was a bit of bullying in the marketplace,” says Weekes.)

Regulators have since separated the right to vote and the right to redeem one’s shares, meaning investors today can vote ‘yes’ or ‘no’ and still redeem their capital, making the voting process more perfunctory and enabling most deals to go through as planned.

I’ve read something about warrants.

That’s because when buying a unit of a SPAC, institutional investors typically get a share of common stock, plus a warrant or a fraction of a warrant, which is a security that entitles the holder to buy more stock of the issuing company at a fixed price at a later date. It’s basically an added sweetener to motivate them to buy into the SPAC.

Are SPACs safer investments than they once were? They haven’t had the best reputation historically.

They’ve “already gone through their junk phase,” suspects Albert Vanderlaan, an attorney in the tech companies group of Orrick, the global law firm. “In the ’90s, these were considered a pretty junky situation,” he says. “They were abused by foreign investors. In the early 2000s, they were still pretty disfavored.” Things could turn on a dime again, he suggests, but over the last couple of years, the players have changed for the better, which is making a big difference.

How much of the money raised does a management team like Hartz and Steckenrider keep?

The rough rule of thumb is 2% of the SPAC value, plus $2 million, says Steckenrider. The 2% roughly covers the initial underwriting fee; the $2 million then covers the operating expenses of the SPAC, from the initial cost to launch it, to legal preparation, accounting, and NYSE or NASDAQ filing fees. It also “provides the reserves for the ongoing due diligence process,” he says.

Is this money like the carry that VCs receive, and do a SPAC’s managers receive it no matter how the SPAC performs?

Yes and yes.

Here’s how Hartz explains it: “On a $200 million SPAC, there’s a $50 million ‘promote’ that is earned.” But “if that company doesn’t perform and, say, drops in half over a year or 18-month period, then the shares are still worth $25 million.”

Hartz calls this “egregious,” though he and Steckenrider formed their SPAC in exactly the same way rather than structure it differently.

Says Steckrider, “We ultimately decided to go with a plain-vanilla structure [because] as a first-time SPAC sponsor, we wanted to make sure that the investment community had as easy as a time as possible understanding our SPAC. We do expect to renegotiate these economics when we go and do the [merger] transaction with the partner company,” he adds.

Does a $200 million SPAC look to acquire a company that’s valued at around the same amount?

No. According to law firm Vinson & Elkins, there’s no maximum size of a target company — only a minimum size (roughly 80% of the funds in the SPAC trust).

In fact, it’s typical for a SPAC to combine with a company that’s two to four times its IPO proceeds in order to reduce the dilutive impact of the founder shares and warrants.

In the case of Hartz’s and Steckenrider’s SPAC (it’s called “one”), they are looking to find a company “that’s approximately four to six times the size of our vehicle of $200 million,” says Hartz, “so that puts us around in the billion dollar range.”

Where does the rest of the money come from if the partner company is many times larger than the SPAC itself?

It comes from PIPE deals, which, like SPACs, have been around forever and come into and out of fashion. These are literally “private investments in public equities” and they get tacked onto SPACs once management has decided on the company with which it wants to merge.

It’s here that institutional investors get different treatment than retail investors, which is why some industry observers are wary of SPACs.

Specifically, a SPAC’s institutional investors — along with maybe new institutional investors that aren’t part of the SPAC — are told before the rest of the world what the acquisition target is under confidentiality agreements so that they can decide if they want to provide further financing for the deal via a PIPE transaction.

The information asymmetry seems unfair. Then again, they’re restricted not only from sharing information but also from trading the shares for a minimum of four months from the time that the initial business combination is made public. Retail investors, who’ve been left in the dark, can trade their shares any time.

How long does a SPAC have to get all of this done?

It varies, but the standard is around two years.

And if they can’t get it done in the designated time frame?

The money goes back to shareholders.

What do you call that phase of the deal after the partner company has been identified and agrees to merge, but before the actual combination?

That’s called the de-SPAC’ing process, and during this stage of things, the SPAC has to obtain shareholder approval, followed by a review and commenting period by the SEC.

Toward the end of this stretch — which can take 12 to 18 weeks altogether — bankers start taking out the new operating team in the style of a traditional roadshow and getting the story out to analysts who cover the industry so that when the combined new company is revealed, it receives the kind of support that keeps public shareholders interested in a company.

Will we see more people from the venture world like Palihapitiya and Hartz start SPACs?

Weekes, the investment banker, says he’s seeing less interest from VCs in sponsoring SPACs and more interest from them in selling their portfolio companies to a SPAC. As he notes, “Most venture firms are typically a little earlier stage investors and are private market investors, but there’s an uptick of interest across the board, from PE firms, hedge funds, long-only mutual funds.”

That might change if Hartz has anything to do with it. “We’re actually out in the Valley, speaking with all the funds and just looking to educate the venture funds,” he says. “We’ve had a lot of requests in. We think we’re going to convert [famed VC] Bill Gurley from being a direct listings champion to the SPAC champion very soon.”

In the meantime, asked if his SPAC has a specific target in mind already, Hartz says it does not. He also takes issue with the word “target.”

Says Hartz, “We prefer ‘partner company.’” A target, he adds, “sounds like we’re trying to assassinate somebody.”

]]>

TechCrunch

TechCrunch

It isn’t like you’re totally clueless, right? You’re probably aware that Paul Ryan now has a SPAC, as does baseball executive Billy Beane and Silicon Valley stalwart Kevin Hartz.

You likely know, too, that brash entrepreneur Chamath Palihapitiya seemed to kick off the craze around SPACs — blank-check companies that are formed for the purpose of merging or acquiring other companies — in 2017 when he raised $600 million for a SPAC. Called Social Capital Hedosophia Holdings, it was ultimately used to take a 49% stake in the British spaceflight company Virgin Galactic.

But how do SPACs come together in the first place, how do they work exactly, and should you be thinking of launching one? We talked this week with a number of people who are right now focused on almost nothing but SPACs to get our questions — and maybe yours, too — answered.

Why are SPACs suddenly sprouting up everywhere?

Kevin Hartz — who we spoke with after his $200 million blank-check company made its stock market debut on Tuesday — said their popularity ties in part to “Sarbanes Oxley and the difficulty in taking a company public the traditional route.”

Troy Steckenrider, an operator who has partnered with Hartz on his newly public company, said the growing popularity of SPACs also ties to a “shift in the quality of the sponsor teams,” meaning that more people like Hartz are shepherding these vehicles versus “people who might not be able to raise a traditional fund historically.”

Don’t forget, too, that there are whole lot of companies that have raised tens and hundreds of millions of dollars in venture capital and whose IPO plans may have been derailed or slowed by the COVID-19 pandemic. Some need a relatively frictionless way to get out the door, and there are plenty of investors who would like to give them that push.

How does one start the process of creating a SPAC?

The process is really no different than a traditional IPO, explains Chris Weekes, a managing director in the capital markets group at the investment bank Cowen. “There’s a roadshow that will incorporate one-on-one meetings between institutional investors like hedge funds and private equity funds and the SPAC’s management team” to drum up interest in the offering.

At the end of it, institutional investors, which also right now include a lot of family offices, buy into the offering, along with a smaller percentage of retail investors.

Who can form a SPAC?

Pretty much anyone who can persuade shareholders to buy its shares.

What happens right after SPAC has raised its capital?

The money is moved into a blind trust until the management team decides which company or companies it wants to acquire. Share prices don’t really move much during this period as no investors know (or should know, at least) what the target company will be yet.

These SPACs all seem to sell their shares at $10 apiece. Why?

Easier accounting? Tradition? It’s not entirely clear, though Weekes says $10 has “always been the unit price” for SPACs and continues to be with the very occasional exception, such as with hedge fund billionaire Bill Ackman’s Pershing Square Capital Management. (Last month it launched a $4 billion SPAC that sold units for $20 each.)

Have SPACs changed structurally over the years?

They have! Years back, when a SPAC told its institutional investors (under NDA) about the company it had settled on buying, these investors would either vote ‘yes’ to the deal if they wanted to keep their money in, or ‘no’ if they wanted to redeem their shares and get out. But sometimes investors would team up and threaten to torpedo a deal if they weren’t given founder shares or other preferential treatment in what was to become the newly combined company. (“There was a bit of bullying in the marketplace,” says Weekes.)

Regulators have since separated the right to vote and the right to redeem one’s shares, meaning investors today can vote ‘yes’ or ‘no’ and still redeem their capital, making the voting process more perfunctory and enabling most deals to go through as planned.

I’ve read something about warrants.

That’s because when buying a unit of a SPAC, institutional investors typically get a share of common stock, plus a warrant or a fraction of a warrant, which is a security that entitles the holder to buy more stock of the issuing company at a fixed price at a later date. It’s basically an added sweetener to motivate them to buy into the SPAC.

Are SPACs safer investments than they once were? They haven’t had the best reputation historically.

They’ve “already gone through their junk phase,” suspects Albert Vanderlaan, an attorney in the tech companies group of Orrick, the global law firm. “In the ’90s, these were considered a pretty junky situation,” he says. “They were abused by foreign investors. In the early 2000s, they were still pretty disfavored.” Things could turn on a dime again, he suggests, but over the last couple of years, the players have changed for the better, which is making a big difference.

How much of the money raised does a management team like Hartz and Steckenrider keep?

The rough rule of thumb is 2% of the SPAC value, plus $2 million, says Steckenrider. The 2% roughly covers the initial underwriting fee; the $2 million then covers the operating expenses of the SPAC, from the initial cost to launch it, to legal preparation, accounting, and NYSE or NASDAQ filing fees. It also “provides the reserves for the ongoing due diligence process,” he says.

Is this money like the carry that VCs receive, and do a SPAC’s managers receive it no matter how the SPAC performs?

Yes and yes.

Here’s how Hartz explains it: “On a $200 million SPAC, there’s a $50 million ‘promote’ that is earned.” But “if that company doesn’t perform and, say, drops in half over a year or 18-month period, then the shares are still worth $25 million.”

Hartz calls this “egregious,” though he and Steckenrider formed their SPAC in exactly the same way rather than structure it differently.

Says Steckrider, “We ultimately decided to go with a plain-vanilla structure [because] as a first-time SPAC sponsor, we wanted to make sure that the investment community had as easy as a time as possible understanding our SPAC. We do expect to renegotiate these economics when we go and do the [merger] transaction with the partner company,” he adds.

Does a $200 million SPAC look to acquire a company that’s valued at around the same amount?

No. According to law firm Vinson & Elkins, there’s no maximum size of a target company — only a minimum size (roughly 80% of the funds in the SPAC trust).

In fact, it’s typical for a SPAC to combine with a company that’s two to four times its IPO proceeds in order to reduce the dilutive impact of the founder shares and warrants.

In the case of Hartz’s and Steckenrider’s SPAC (it’s called “one”), they are looking to find a company “that’s approximately four to six times the size of our vehicle of $200 million,” says Hartz, “so that puts us around in the billion dollar range.”

Where does the rest of the money come from if the partner company is many times larger than the SPAC itself?

It comes from PIPE deals, which, like SPACs, have been around forever and come into and out of fashion. These are literally “private investments in public equities” and they get tacked onto SPACs once management has decided on the company with which it wants to merge.

It’s here that institutional investors get different treatment than retail investors, which is why some industry observers are wary of SPACs.

Specifically, a SPAC’s institutional investors — along with maybe new institutional investors that aren’t part of the SPAC — are told before the rest of the world what the acquisition target is under confidentiality agreements so that they can decide if they want to provide further financing for the deal via a PIPE transaction.

The information asymmetry seems unfair. Then again, they’re restricted not only from sharing information but also from trading the shares for a minimum of four months from the time that the initial business combination is made public. Retail investors, who’ve been left in the dark, can trade their shares any time.

How long does a SPAC have to get all of this done?

It varies, but the standard is around two years.

And if they can’t get it done in the designated time frame?

The money goes back to shareholders.

What do you call that phase of the deal after the partner company has been identified and agrees to merge, but before the actual combination?

That’s called the de-SPAC’ing process, and during this stage of things, the SPAC has to obtain shareholder approval, followed by a review and commenting period by the SEC.

Toward the end of this stretch — which can take 12 to 18 weeks altogether — bankers start taking out the new operating team in the style of a traditional roadshow and getting the story out to analysts who cover the industry so that when the combined new company is revealed, it receives the kind of support that keeps public shareholders interested in a company.

Will we see more people from the venture world like Palihapitiya and Hartz start SPACs?

Weekes, the investment banker, says he’s seeing less interest from VCs in sponsoring SPACs and more interest from them in selling their portfolio companies to a SPAC. As he notes, “Most venture firms are typically a little earlier stage investors and are private market investors, but there’s an uptick of interest across the board, from PE firms, hedge funds, long-only mutual funds.”

That might change if Hartz has anything to do with it. “We’re actually out in the Valley, speaking with all the funds and just looking to educate the venture funds,” he says. “We’ve had a lot of requests in. We think we’re going to convert [famed VC] Bill Gurley from being a direct listings champion to the SPAC champion very soon.”

In the meantime, asked if his SPAC has a specific target in mind already, Hartz says it does not. He also takes issue with the word “target.”

Says Hartz, “We prefer ‘partner company.’” A target, he adds, “sounds like we’re trying to assassinate somebody.”

]]>

TechCrunch

TechCrunch

It isn’t like you’re totally clueless, right? You’re probably aware that Paul Ryan now has a SPAC, as does baseball executive Billy Beane and Silicon Valley stalwart Kevin Hartz.

You likely know, too, that brash entrepreneur Chamath Palihapitiya seemed to kick off the craze around SPACs — blank-check companies that are formed for the purpose of merging or acquiring other companies — in 2017 when he raised $600 million for a SPAC. Called Social Capital Hedosophia Holdings, it was ultimately used to take a 49% stake in the British spaceflight company Virgin Galactic.

But how do SPACs come together in the first place, how do they work exactly, and should you be thinking of launching one? We talked this week with a number of people who are right now focused on almost nothing but SPACs to get our questions — and maybe yours, too — answered.

Why are SPACs suddenly sprouting up everywhere?

Kevin Hartz — who we spoke with after his $200 million blank-check company made its stock market debut on Tuesday — said their popularity ties in part to “Sarbanes Oxley and the difficulty in taking a company public the traditional route.”

Troy Steckenrider, an operator who has partnered with Hartz on his newly public company, said the growing popularity of SPACs also ties to a “shift in the quality of the sponsor teams,” meaning that more people like Hartz are shepherding these vehicles versus “people who might not be able to raise a traditional fund historically.”

Don’t forget, too, that there are whole lot of companies that have raised tens and hundreds of millions of dollars in venture capital and whose IPO plans may have been derailed or slowed by the COVID-19 pandemic. Some need a relatively frictionless way to get out the door, and there are plenty of investors who would like to give them that push.

How does one start the process of creating a SPAC?

The process is really no different than a traditional IPO, explains Chris Weekes, a managing director in the capital markets group at the investment bank Cowen. “There’s a roadshow that will incorporate one-on-one meetings between institutional investors and the SPAC’s management team” to drum up interest in the offering.

At the end of it, institutional investors like mutual funds, private equity funds, and family offices buy into the offering, along with a smaller percentage of retail investors.

Who can form a SPAC?

Pretty much anyone who can persuade shareholders to buy its shares.

What happens right after SPAC has raised its capital?

The money is moved into a blind trust until the management team decides which company or companies it wants to acquire. Share prices don’t really move much during this period as no investors know (or should know, at least) what the target company will be yet.

These SPACs all seem to sell their shares at $10 apiece. Why?

Easier accounting? Tradition? It’s not entirely clear, though Weekes says $10 has “always been the unit price” for SPACs and continues to be with the very occasional exception, such as with hedge fund billionaire Bill Ackman’s Pershing Square Capital Management. (Last month it launched a $4 billion SPAC that sold units for $20 each.)

Have SPACs changed structurally over the years?

They have! Years back, when a SPAC told its institutional investors (under NDA) about the company it had settled on buying, these investors would either vote ‘yes’ to the deal if they wanted to keep their money in, or ‘no’ if they wanted to redeem their shares and get out. But sometimes investors would team up and threaten to torpedo a deal if they weren’t given founder shares or other preferential treatment in what was to become the newly combined company. (“There was a bit of bullying in the marketplace,” says Weekes.)

Regulators have since separated the right to vote and the right to redeem one’s shares, meaning investors today can vote ‘yes’ or ‘no’ and still redeem their capital, making the voting process more perfunctory and enabling most deals to go through as planned.

I’ve read something about warrants.

That’s because when buying a unit of a SPAC, institutional investors typically get a share of common stock, plus a warrant or a fraction of a warrant, which is a security that entitles the holder to buy more stock of the issuing company at a fixed price at a later date. It’s basically an added sweetener to motivate them to buy into the SPAC.

Are SPACs safer investments than they once were? They haven’t had the best reputation historically.

They’ve “already gone through their junk phase,” suspects Albert Vanderlaan, an attorney in the tech companies group of Orrick, the global law firm. “In the ’90s, these were considered a pretty junky situation,” he says. “They were abused by foreign investors. In the early 2000s, they were still pretty disfavored.” Things could turn on a dime again, he suggests, but over the last couple of years, the players have changed for the better, which is making a big difference.

How much of the money raised does a management team like Hartz and Steckenrider keep?

The rough rule of thumb is 2% of the SPAC value, plus $2 million, says Steckenrider. The 2% roughly covers the initial underwriting fee; the $2 million then covers the operating expenses of the SPAC, from the initial cost to launch it, to legal preparation, accounting, and NYSE or NASDAQ filing fees. It’s also “provides the reserves for the ongoing due diligence process,” he says.

Is this money like the carry that VCs receive, and do a SPAC’s managers receive it no matter how the SPAC performs?

Yes and yes.

Here’s how Hartz explains it: “On a $200 million SPAC, there’s a $50 million ‘promote’ that is earned at $10 a share if the transaction consummates at $10 a share,” which, again, is always the traditional size of a SPAC. “But if that company doesn’t perform and, say, drops in half over a year or 18-month period, then the shares are still worth $25 million.”

Hartz calls this “egregious,” though he and Steckenrider formed their SPAC in exactly the same way rather than structure it differently.

Says Steckrider, “We ultimately decided to go with a plain-vanilla structure [because] as a first-time spec sponsor, we wanted to make sure that the investment community had as as easy as a time as possible understanding our SPAC. We do expect to renegotiate these economics when we go and do the [merger] transaction with the partner company,” he adds.

Does a $200 million SPAC look to acquire a company that’s valued at around the same amount?

No. According to law firm Vinson & Elkins, there’s no maximum size of a target company — only a minimum size (roughly 80% of the funds in the SPAC trust).

In fact, it’s typical for a SPAC to combine with a company that’s two to four times its IPO proceeds in order to reduce the dilutive impact of the founder shares and warrants.

In the case of Hartz’s and Steckenrider’s SPAC (it’s called One), they are looking to find a company “that’s approximately four to six times the size of our vehicle of $200 million,” says Harzt, “so that puts us around in the billion dollar range.”

Where does the rest of the money come from if the partner company is many times larger than the SPAC itself?

It comes from PIPE deals, which, like SPACs, have been around forever and come into and out of fashion. These are literally “private investments in public equities” and they get tacked onto SPACs once management has decided on the company with which it wants to merge.

It’s here that institutional investors get different treatment than retail investors, which is why some industry observers are wary of SPACs.

Specifically, a SPAC’s institutional investors — along with maybe new institutional investors that aren’t part of the SPAC — are told before the rest of the world what the acquisition target is under confidentiality agreements so that they can decide if they want to provide further financing for the deal via a PIPE transaction.

The information asymmetry seems unfair. Then again, they’re restricted not only from sharing information but also from trading the shares for a minimum of four months from the time that the initial business combination is made public. Retail investors, who’ve been left in the dark, can trade their shares any time.

How long does a SPAC have to get all of this done?

It varies, but the standard is around two years.

And if they can’t get it done in the designated time frame?

The money goes back to shareholders.

What do you call that phase of the deal after the partner company has been identified and agrees to merge, but before the actual combination?

That’s called the de-SPAC’ing process, and during this stage of things, the SPAC has to obtain shareholder approval, followed by a review and commenting period by the SEC.

Toward the end of this stretch — which can take 12 to 18 weeks altogether — bankers start taking out the new operating team in the style of a traditional roadshow and getting the story out to analysts who cover the industry so that when the combined new company is revealed, it receives the kind of support that keeps public shareholders interested in a company.

Will we see more people from the venture world like Palihapitiya and Hartz start SPACs?

Weekes, the investment banker, says he’s seeing less interest from VCs in sponsoring SPACs and more interest from them in selling their portfolio companies to a SPAC. As he notes, “Most venture firms are typically a little earlier stage investors and are private market investors, but there’s an uptick of interest across the board, from PE firms, hedge funds, long-only mutual funds.”

That might change if Hartz has anything to do with it. “We’re actually out in the Valley, speaking with all the funds and just looking to educate the venture funds,” he says. “We’ve had a lot of requests in. We think we’re going to convert [famed VC] Bill Gurley from being a direct listings champion to the SPAC champion very soon.”

In the meantime, asked if his SPAC has a specific target in mind already, Hartz says it does not. He also takes issue with the word “target.”

Says Hartz, “We prefer ‘partner company.’ A target sounds like we’re trying to assassinate somebody.”

]]>

TechCrunch

TechCrunch

Initially, the app store intelligence firm Apptopia crunched the numbers around Triller’s downloads and found the claim of 250 million downloads to be inflated. According to its analysis, Apptopia had estimated Triller’s app has been downloaded 52 million times since launch across both iOS and Google Play worldwide, not 250 million times, as Triller had said.

TechCrunch reached out to Triller for comment on Apptopia’s findings. Triller and Apptopia then ended up independently getting in touch with one another, through a shared investor. After some back-and-forth between the two, Apptopia decided to pull its report.

During this time, Triller also threatened to sue Apptopia for providing false information in a comment provided to TechCrunch.

Triller CEO Mike Lu told TechCrunch, via an emailed statement, that Apptopia “clearly have allowed themselves to become a pawn of these giant conglomerates, especially those like TikTok who we are in active litigation with for stealing our patents.” (Lu was referring to the recent lawsuit Triller filed against TikTok over patent infringement.)

“We would have welcomed Apptopia with open arms had they just reached out to us, and helped them understand our numbers, and now they have just made themselves part of our TikTok litigation,” Lu threatened. “We will be pursuing a claim against them for spreading harmful, false and knowingly damaging information,” he said.

This is a fairly aggressive response over a dispute about app store downloads. Industry insiders understand that none of the app store analytics firms have perfectly accurate figures. Meanwhile, regular consumers can get a sense of how popular an app is just by looking at the app store’s top charts, which are public.

For further context around the now heavily disputed download number, we asked mobile data and analytics firm App Annie and app store intelligence firm Sensor Tower for their own Triller data. App Annie declined to share downloads, but shared ranking data. Sensor Tower’s data, meanwhile, indicated Triller had reached 45.6 million total global installs across iOS and Android since its launch. That’s even lower than the 52 million figure Triller had vehemently disputed.

Sensor Tower suggested the discrepancies between third-party estimates and Triller’s own numbers could have to do with how Triller counted its installs. Some publishers count other forms of installs, like re-installs, updates and direct installs of Android APKs (meaning, installs outside of Google Play). Third-party firms don’t see these figures. Third-party firms also don’t count things like re-installs because that’s effectively counting the same user twice. Sensor Tower, of course, doesn’t know how Triller was counting installs internally.

Though Apptopia is no longer standing behind its original report and estimate of 52 million installs, its report contained some other interesting insights that are still worth looking at, as they don’t rely on its forecasting technology.

For instance, Triller recently told CNBC it had 65 million monthly active users (MAUs). Counting an app’s MAUs is a way to measure its current usage and popularity. This tends to be a much smaller figure than an app’s total downloads, as not everyone who tries out an app sticks with it as a regular user.

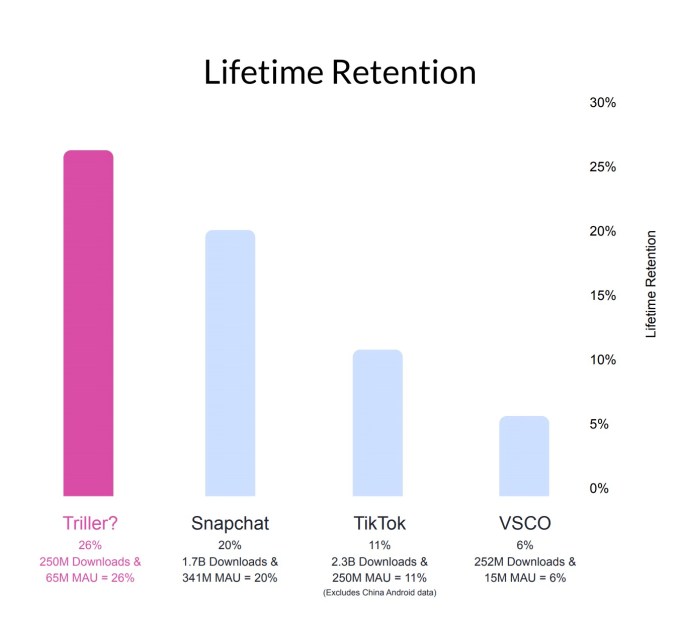

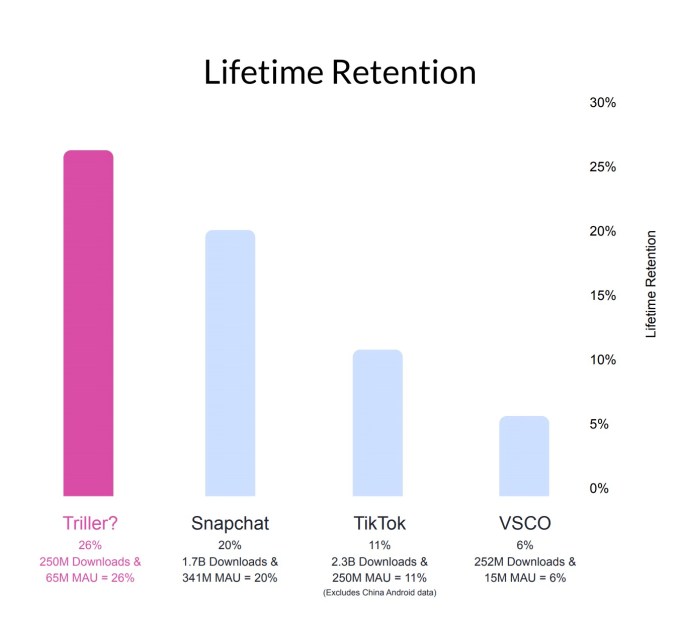

Using Triller’s own download figure of 250 million and its own 65 million MAU figure, it’s claiming a lifetime retention rate of 26%. (The lifetime retention rate is determining the percentage of the app’s total downloads the current MAU number represents.) Triller’s rate is well above what the best apps in the industry are able to achieve.

Snapchat has a lifetime retention rate of 20%, for example. TikTok has an 11% lifetime retention rate. Triller’s is higher, based on its own figures.

Triller’s response to this part of the claim is that its app has changed a lot since its 2015 launch. It didn’t become a social media platform, for example, until 2018. It says if you look at the 90-120 day retention figures for TikTok or Snap, they would be above 30%, which is how its numbers should be compared.

Image Credits: Apptopia

Apptopia’s report also pointed to Triller’s App Store and Google Play chart rankings as another data point in questioning Triller’s download claims.

For those unfamiliar, the app store chart rankings are driven by downloads combined with other factors, like velocity of downloads, ratings, user retention and more.

Image Credits: Apptopia

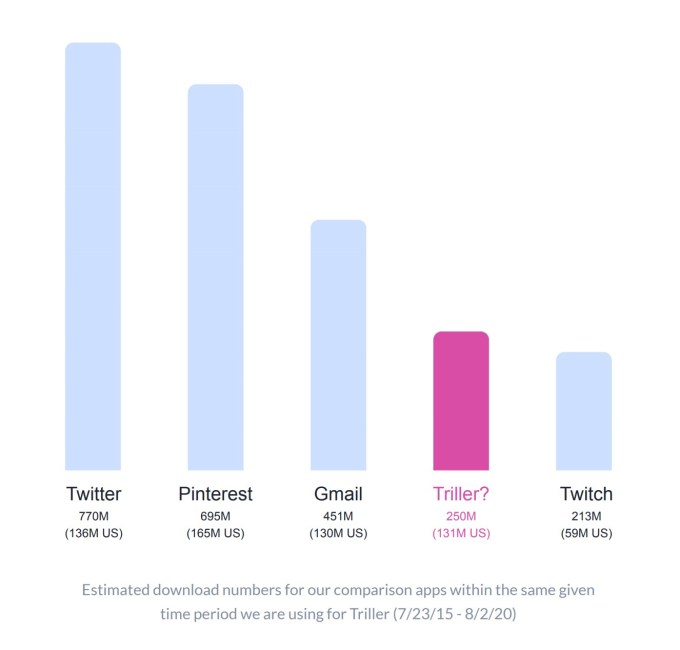

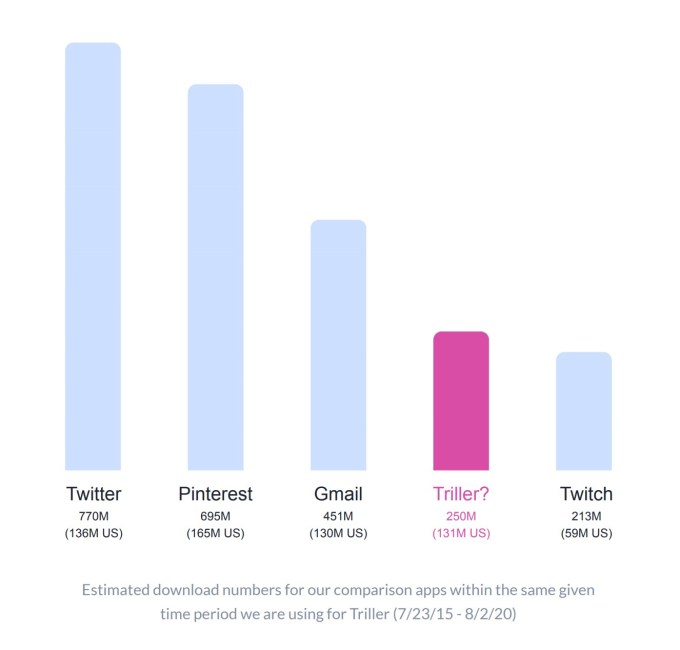

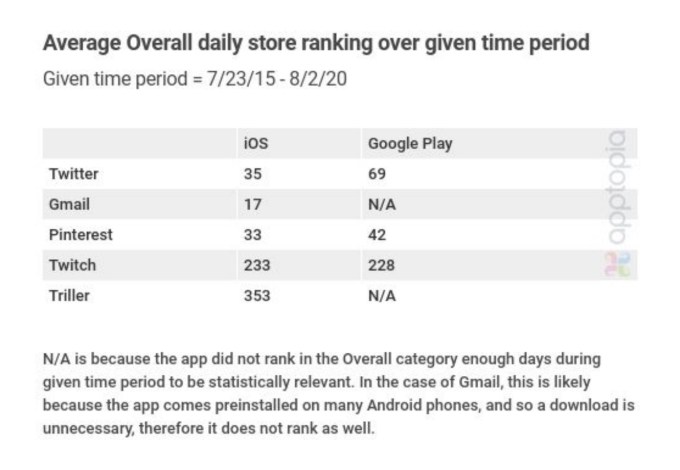

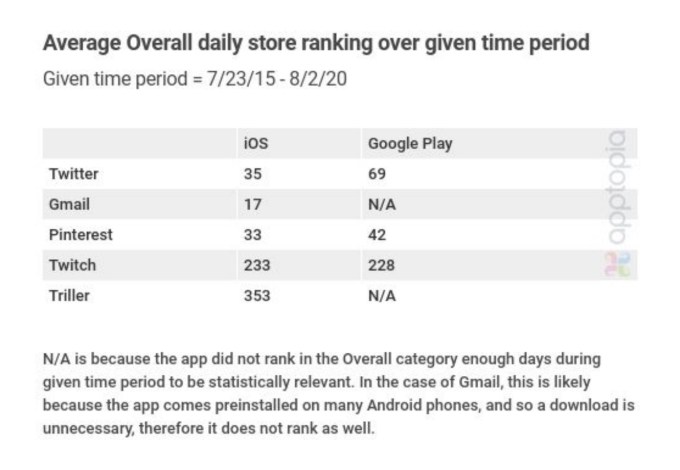

To analyze Triller’s claim in the context of its chart rankings, Apptopia examined several other popular U.S. apps for comparison’s sake, including Twitter, Pinterest, Gmail and Twitch.

These apps were selected because they had a similar number of U.S. downloads to Triller for the time period Apptopia used to analyze Triller’s claim: July 23, 2015-August 2, 2020. The former is the date of Triller’s launch and the latter is when it issued a press release stating its 250 million download figure.

Image Credits: Apptopia

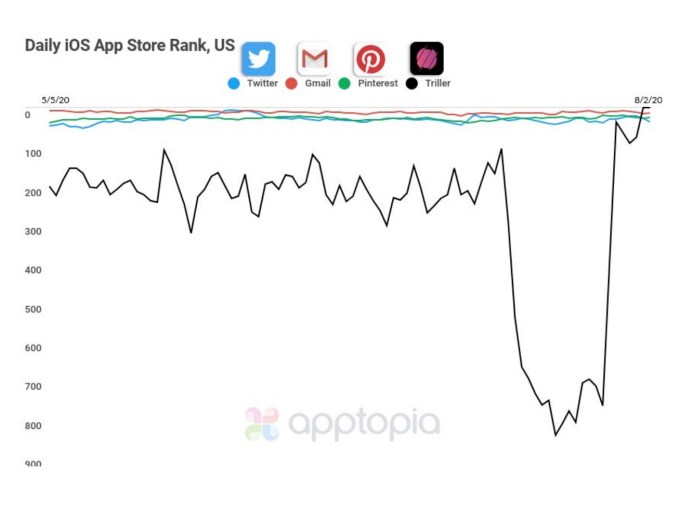

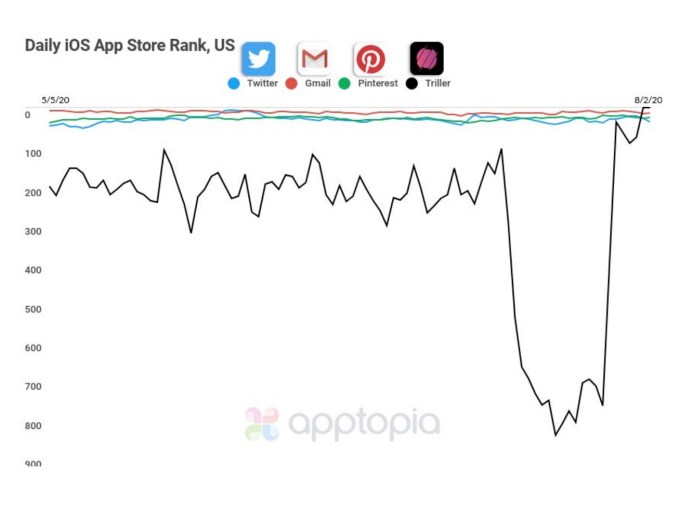

Simply put, if Triller’s 250 million figure was correct, then the app would seemingly appear much higher on the U.S. App Store and Google Play charts than it does.

On iOS, the average overall ranking for Gmail during this time period was No. 17, Twitter was No. 35, Pinterest was No. 33 and Twitch was No. 233. Triller, meanwhile, was No. 353. (Twitch is lower than the others because it’s a less-used app, because chart rankings aren’t entirely download-dependent and because many Twitch users stream on the desktop, not mobile. But even it ranks higher than Triller.)

You can see that Triller consistently trends well below the others in the U.S. charts. This trend is even clearer when zoomed into the last 90 days (see below).

Apptopia’s estimate here is also in line with App Annie’s data. Though App Annie couldn’t pull a lifetime average rank, as Apptopia did, it was able to pull Triller’s average U.S. iPhone App Store Overall rank for the past 90 days, which was No. 303.

Image Credits: Apptopia

A similar trend can be seen on Google Play, where Triller doesn’t even rank in the Overall category enough days during the given time frame to be statistically relevant. (Gmail didn’t either, but that’s because the app is preinstalled on many Android phones, so users don’t need to download it.)

Triller’s response to this claim is that it, again, was a different app before 2018 and it has hit No. 1 in many non-U.S. markets, including Korea, where it’s currently No. 1. In the last 10 days, it has been No. 1 in Pakistan, Indonesia, Brazil, Mexico, Italy and France, and in the last 30 days in India, U.S., South Africa, Nigeria and dozens of others.

“Our growth and numbers are very fresh and very new, so taking anything long term or just the U.S. is neither relevant nor applicable to us,” said Triller CEO Mike Lu.

Image Credits: App Annie

The timing of Triller’s claim of 250 million downloads follows reports that said the startup is raising hundreds of millions in new funding. Fox Business recently reported Triller has “commitments from investors of $200 million to $300 million.” Pegasus Tech Ventures, a Triller investor, emailed journalists in early August to pitch Triller coverage, saying the app was “now raising around $250m at a $1B valuation.”

Triller also recently made news for suing TikTok over patent infringement, verified in court filings TechCrunch pulled from PACER.

None of this is coincidental. Triller has been angling to become the TikTok alternative that wins the U.S. market in the event TikTok can’t get a deal done in the time allotted by Trump’s executive order requiring TikTok to sell its U.S. operations or be banned in the country.

Mr. Lu disputed claims made by third-party mobile data firms, when reached for comment. The company stands by its numbers.

“No app intelligence firm has been provided our data,” Lu said. “Any numbers they provide have no relevance or accuracy to our numbers. We are able to validate each and every one of our users. They should also disclose which of our competitors are paying them hundreds of thousands of dollars such as TikTok,” he added.

Lu also openly wondered if a Triller competitor was feeding false information. His full statement is below:

The biggest app intelligence firms have less than 1M total users/customers and less than a few hundred large companies actually providing them real data, any numbers they present are based solely on guessing based on a very small sample group and are far from accurate. The terms of service of all app intelligence firms state that any numbers they provide come from their own guesstimates. While certain companies pay upwards of a few hundred thousand dollars to these firms and give them access to their numbers, we have not provided such access. Any numbers provided by them are wholly inaccurate and they themselves state they have no actual way of validating without us providing them access. These is clearly just a transparent attack by one of our competitors who pays them handsomely to disseminate this false information. It’s sad to see firms that are supposed to be neutral and claim to be pro entrepreneurial and pro American allow themselves to become a pawn of these giant conglomerates, especially those like TikTok who we are in active litigation with for them stealing our patents.”

Following their conversation with Triller, Apptopia tells us it will soon have access to more accurate figures for Triller and will release those at a later time. The companies seem to be working things out.

Apptopia says:

We are working closely with Triller who has been very transparent and is opening up all of their analytics accounts to Apptopia. We are working on internal reports and working with Triller to create the most accurate and up to date data over the short term. Between their tremendous success in emerging mobile markets, which are typically hard to model, (i.e. India, Africa, etc.) and the fact that Triller’s growth is very recent, it is especially hard to compare to peers who have years of growth and history. We feel strongly about publishing the most accurate estimates, and the best way for us to do that is to work hand in hand with Triller and authenticate their real data. We plan to do this over the coming weeks and do our best to be the source of truth on the matter.

]]>

TechCrunch

TechCrunch

Albion College, a small liberal arts school in Michigan, said in June it would allow its nearly 1,500 students to return to campus for the new academic year starting in August. Lectures would be limited in size and the semester would finish by Thanksgiving rather than December. The school said it would test both staff and students upon their arrival to campus and throughout the academic year.

But less than two weeks before students began arriving on campus, the school announced it would require them to download and install a contact-tracing app called Aura, which it says will help it tackle any coronavirus outbreak on campus.

There’s a catch. The app is designed to track students’ real-time locations around the clock, and there is no way to opt out.

The Aura app lets the school know when a student tests positive for COVID-19. It also comes with a contact-tracing feature that alerts students when they have come into close proximity with a person who tested positive for the virus. But the feature requires constant access to the student’s real-time location, which the college says is necessary to track the spread of any exposure.

The school’s mandatory use of the app sparked privacy concerns and prompted parents to launch a petition to make using the app optional.

Worse, the app had at least two security vulnerabilities only discovered after the app was rolled out. One of the vulnerabilities allowed access to the app’s back-end servers. The other allowed us to infer a student’s COVID-19 test results.

The vulnerabilities were fixed. But students are still expected to use the app or face suspension.

Track and trace

Exactly how Aura came to be and how Albion became its first major customer is a mystery.

Aura was developed by Nucleus Careers in the months after the pandemic began. Nucleus Careers is a Pennsylvania-based recruiting firm founded in 2020, with no apparent history or experience in building or developing healthcare apps besides a brief mention in a recent press release. The app was built in partnership with Genetworx, a Virginia-based lab providing coronavirus tests. (We asked Genetworx about the app and its involvement, but TechCrunch did not hear back from the company.)

The app helps students locate and schedule COVID-19 testing on campus. Once a student is tested for COVID-19, the results are fed into the app.

If the test comes back negative, the app displays a QR code which, when scanned, says the student is “certified” free of the virus. If the student tests positive or has yet to be tested, the student’s QR code will read “denied.”

Aura uses the student’s real-time location to determine if they have come into contact with another person with the virus. Most other contact-tracing apps use nearby Bluetooth signals, which experts say is more privacy-friendly.

Hundreds of academics have argued that collecting and storing location data is bad for privacy.

The Aura app generates a QR code based on the student’s COVID-19 test results. Scan the QR code to reveal the student’s test result status. (Image: TechCrunch)

In addition to having to install the app, students were told they are not allowed to leave campus for the duration of the semester without permission over fears that contact with the wider community might bring the virus back to campus.

If a student leaves campus without permission, the app will alert the school, and the student’s ID card will be locked and access to campus buildings will be revoked, according to an email to students, seen by TechCrunch.

Students are not allowed to turn off their location and can be suspended and “removed from campus” if they violate the policy, the email read.

Private universities in the U.S. like Albion can largely set and enforce their own rules and have been likened to “shadow criminal justice systems — without any of the protections or powers of a criminal court,” where students can face discipline and expulsion for almost any reason with little to no recourse. Last year, TechCrunch reported on a student at Tufts University who was expelled for alleged grade hacking, despite exculpatory evidence in her favor.

Albion said in an online Q&A that the “only time a student’s location data will be accessed is if they test positive or if they leave campus without following proper procedure.” But the school has not said how it will ensure that student location data is not improperly accessed, or who has access.

“I think it’s more creepy than anything and has caused me a lot of anxiety about going back,” one student going into their senior year, who asked not to be named, told TechCrunch.

A ‘rush job’

One Albion student was not convinced the app was safe or private.

The student, who asked to go by her Twitter handle @Q3w3e3, decompiles and analyzes apps on the side. “I just like knowing what apps are doing,” she told TechCrunch.

Buried in the app’s source code, she found hardcoded secret keys for the app’s backend servers, hosted on Amazon Web Services. She tweeted her findings — with careful redactions to prevent misuse — and reported the problems to Nucleus, but did not hear back.

A security researcher, who asked to go by her handle Gilda, was watching the tweets about Aura roll in. Gilda also dug into the app and found and tested the keys.

“The keys were practically ‘full access’,” Gilda told TechCrunch. She said the keys — since changed — gave her access to the app’s databases and cloud storage in which she found patient data, including COVID-19 test results with names, addresses and dates of birth.

Nucleus pushed out an updated version of the app on the same day with the keys removed, but did not acknowledge the vulnerability.

TechCrunch also wanted to look under the hood to see how Aura works. We used a network analysis tool, Burp Suite, to understand the network data going in and out of the app. (We’ve done this a few times before.) Using our spare iPhone, we registered an Aura account and logged in. The app normally pulls in recent COVID-19 tests. In our case, we didn’t have any and so the scannable QR code, generated by the app, declared that I had been “denied” clearance to enter campus — as to be expected.

But our network analysis tool showed that the QR code was not generated on the device but on a hidden part of Aura’s website. The web address that generated the QR code included the Aura user’s account number, which isn’t visible from the app. If we increased or decreased the account number in the web address by a single digit, it generated a QR code for that user’s Aura account.

In other words, because we could see another user’s QR code, we could also see the student’s full name, their COVID-19 test result status and what date the student was certified or denied.

TechCrunch did not enumerate each QR code, but through limited testing found that the bug may have exposed about 15,000 QR codes.

We described the app’s vulnerabilities to Will Strafach, a security researcher and chief executive at Guardian Firewall. Strafach said the app sounded like a “rush job,” and that the enumeration bug could be easily caught during a security review. “The fact that they were unaware tells me they did not even bother to do this,” he said. And, the keys left in the source code, said Strafach, suggested “a ‘just-ship-it’ attitude to a worrisome extreme.”

An email sent by Albion president Matthew Johnson, dated August 18 and shared with TechCrunch, confirmed that the school has since launched a security review of the app.

We sent Nucleus several questions — including about the vulnerabilities and if the app had gone through a security audit. Nucleus fixed the QR code vulnerability after TechCrunch detailed the bug. But a spokesperson for the company, Tony Defazio, did not provide comment. “I advised the company of your inquiry,” he said. The spokesperson did not return follow-up emails.

In response to the student’s findings, Albion said that the app was compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, or HIPAA, which governs the privacy of health data and medical records. HIPAA also holds companies — including universities — accountable for security lapses involving health data. That can mean heavy fines or, in some cases, prosecution.

Albion spokesperson Chuck Carlson did not respond to our emails requesting comment.

At least two other schools, Bucknell University and Temple University, are reopening for the fall semester by requiring students to present two negative COVID-19 tests through Genetworx. The schools are not using Aura, but their own in-house student app to deliver the test results.

Albion students, meanwhile, are split on whether to comply, or refuse and face the consequences. @Q3w3e3 said she will not use the app. “I’m trying to work with the college to find an alternative way to be tested,” she told TechCrunch.

Parents have also expressed their anger at the policy.

“I absolutely hate it. I think it’s a violation of her privacy and civil liberties,” said Elizabeth Burbank, a parent of an Albion student, who signed the petition against the school’s tracking effort.

“I do want to keep my daughter safe, of course, and help keep others safe as well. We are more than happy to do our part. I do not believe however, a GPS tracker is the way to go,” she said. “Wash our hands. Eat healthy. And keep researching treatments and vaccines. That should be our focus.

“I do intend to do all I can to protect my daughter’s right to privacy and challenge her right to free movement in her community,” she said.

Send tips securely over Signal and WhatsApp to +1 646-755-8849 or send an encrypted email to: zack.whittaker@protonmail.com

]]>