TechCrunch

TechCrunch

REEF began its life as Miami-based ParkJockey, providing hardware, software and management services for parking lots. It has since expanded its vision while remaining true to its basic business model. While it still manages parking lots, it now it adds infrastructure for cloud kitchens, healthcare clinics, logistics and last-mile delivery, and even old school brick and mortar retail and experiential consumer spaces on top of those now-empty parking structures and spaces.

Like WeWork, REEF leases most of the real estate it operates and upgrades it before leasing it to other occupants (or using the spaces itself). Unlike WeWork, the business actually has a fair shot at working out — especially given business trends that have accelerated in response to the health and safety measures implemented to stop the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In part that’s because REEF does operate its own businesses on the premises and works with startups to provide actual goods and services that are location dependent for their success and revenue generating.

The money will be used to scale from its roughly 4,800 locations to 10,000 new locations around the country and to transform the parking lots into “neighborhood hubs,” according to Ari Ojalvo, the company’s co-founder and chief executive.

SoftBank and Mubadala are joining private equity and financial investment giants Oaktree, UBS Asset Management and the European venture capital firm Target Global in providing the cash for the massive equity financing. Meanwhile, REEF Technology and Oaktree are collaborating on a $300 million real estate investment vehicle, the Neighborhood Property Group, as Bloomberg reported on Monday.

In all, REEF, which could reasonably be described as a WeWork for the neighborhood store, has $1 billion in capital coming to build out what it calls a proximity-as-a-service platform.

Since taking a minority investment from SoftBank back in 2018 (an investment which reportedly valued the company at $1 billion) and transforming from ParkJockey into REEF Technology, the company added a booming cloud kitchen business to support the increase in virtual restaurant chains.

In addition, it added a number of service providers as partners, including last-mile delivery startup Bond (and the logistics giant, DHL); the national primary healthcare services clinic operator and technology developer, Carbon Health; the electric vehicle charging and maintenance provider, Get Charged; and — at its operations in London — the new vertical farm developer, Crate to Plate (Ojalvo said it was in talks with the established vertical farming companies in the U.S. on potential partnerships).

Next year, the company plans to launch the first of its experiential, open-air entertainment venues at a space it operates in Austin, according to Ojalvo.

And further down the road, the company sees an opportunity to serve as a hub for the kinds of data-processing centers and telecommunications gateways that will power the smart city of the 21st century, Ojalvo said.

“We have inbound interest from companies that do edge computing and companies getting ready with 5G,” he said. “Data and infrastructure is a big part of our neighborhood hub. It’s like electricity. Without electricity and connectivity, we don’t have the world we want to see.”

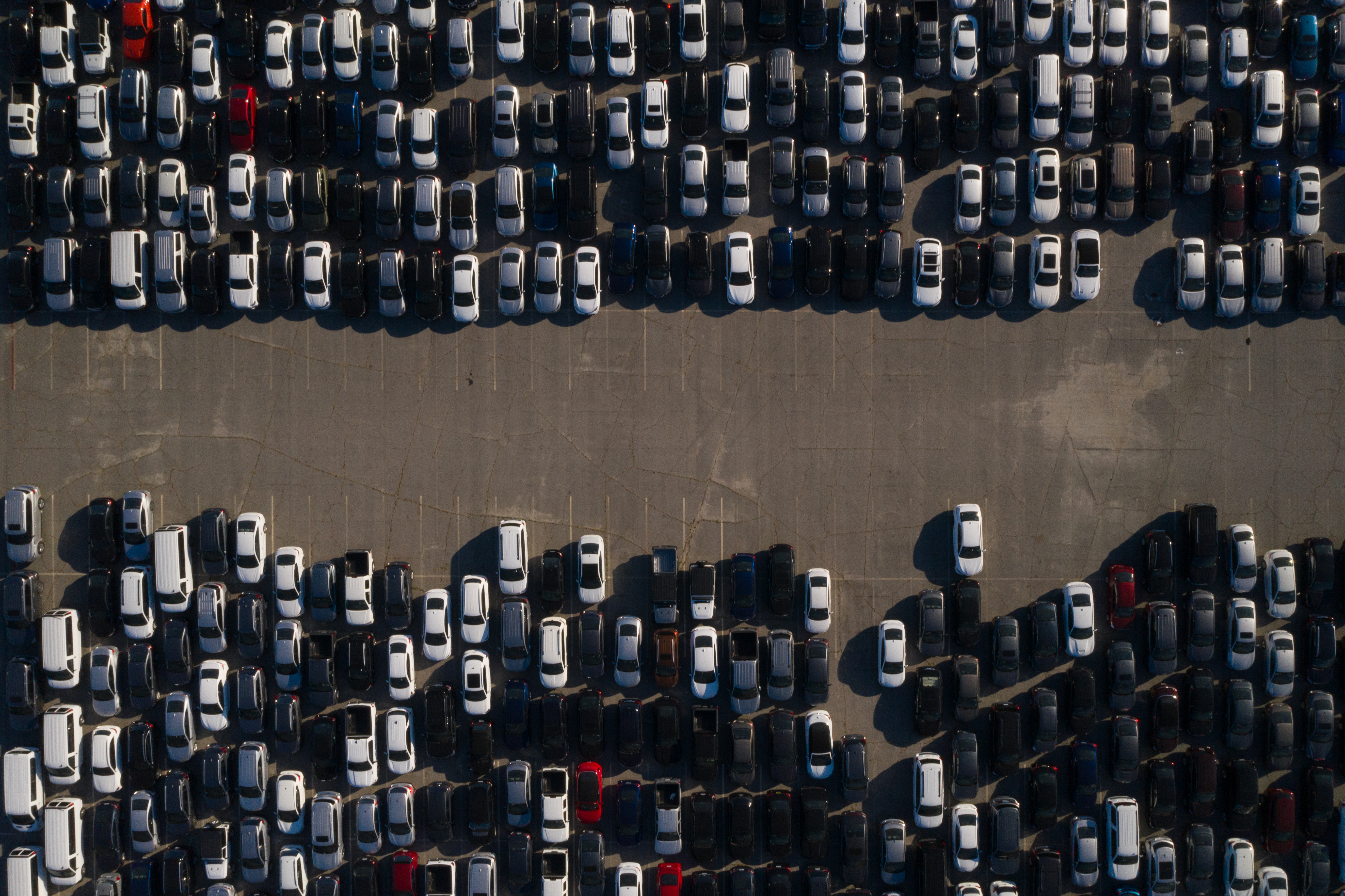

Rental cars are stored in a parking lot at Dodger Stadium in this aerial photograph taken over Los Angeles, California, U.S., on Wednesday, May 27, 2020. Hertz Global Holdings Inc. will sell as many of its rental cars as possible while in bankruptcy to bring its huge fleet in line with reduced future demand in a post-pandemic economy.

The bulk of the company’s revenue is coming from its parking business, but Ojalvo expects that to change as the its cloud kitchen business continues to grow. “Neighborhood Kitchens will be a significant part of non-parking revenue,” said Ojalvo.

REEF already operates more than 100 Neighborhood Kitchens across more than 20 markets in North America, and that number will only grow as the company expands its regional footprint. It’s hosting virtual kitchens from celebrity chefs like David Chang’s Fuku, and, according to the company, offering lifelines to beloved local restaurateurs like the chain Jack’s Wife Freda in New York or Michelle Bernstein’s kitchens in Miami.

These restaurants are, in some cases, taking advantage of the employees that REEF Technology has operating its network of kitchens. It’s another difference between WeWork and REEF. The company not only provides the space, in many instances it’s providing the labor that’s allowing businesses to scale.

The company already employs over a thousand kitchen workers prepping food at its restaurants. And REEF acquired a company earlier in May to consolidate its back-end service for on-demand deliveries.

That same strategy will likely apply to other aspects of the company’s services, as well.

“We’re building a platform of proximity,” says Ojalvo. “That proximity is driven through an install base that’s in parking lots or parking garages… [and] that enables all sorts of companies to use its proximity as a platform. To basically build their marketplaces.”

CARDIFF, UNITED KINGDOM – DECEMBER 22: A Deliveroo rider at work at night on December 22, 2018 in Cardiff, United Kingdom. (Photo by Matthew Horwood/Getty Images)

As REEF raises money for expansion, it’s tapping into a new theory of urban development embraced by mayors from Amsterdam to Tempe, Ariz. calling for a 15-minute city (one where the amenities needed for a comfortable urban existence are no more than 15 minutes away).

It’s a worthwhile goal, but while mayors seem to place the emphasis on the availability of accessible amenities, REEF’s leadership acknowledges that only a few of its parking lots and garages will be multi-use and accessible to neighborhood residents. According to a spokesman, only several hundred of the company’s planned 10,000 businesses will have the kind of multi-use mall environment that encourages neighborhood access. Instead, its business seems to be based on the notion that most delivery services should be no more than 15 minutes away.

It’s a different project, but it also has a number of supporters. One could argue that cloud kitchen providers like Zuul, Kitchen United, and Travis Kalanick’s Cloud Kitchens all ascribe to the same belief. Kalanick, the Uber co-founder and former CEO whose company received billions from SoftBank, has been snapping up properties in the US and Asia under an investment vehicle called City Storage Systems, which also uses parking lots and abandoned malls as fulfillment centers.

Big retailers also have taken notice of the new revenue stream and one of America’s largest, Kroger, is even running a ghost kitchen experiment in the Midwest.

If that’s not enough, there are plenty of under-utilized assets that are already on the market thanks to the economic downturn wrought by the COVID-19 pandemic and the government’s efforts to contain it.

“I guess a lot depends on how you think delivery players work out in the coming years versus say drive through or curbside pickup which seems to be where large national players are focused (Starbucks, McDonalds, Dominos, etc),” wrote on venture investor in an email. “But how do delivery players use these spaces versus say lots of low cost retail spaces that can be used to staging or package returns. Maybe there is a play to add modular or prefab units to the existing parking spaces on provide flex for scaling, but it’s not clear that anyone is growing at a frantic pace… I’m just not sure how to see converted parking versus other… commercial spaces for retail or office that are all searching for new applications.”

REEF Technology last mile delivery vehicle and DHL-branded vehicle. Image Credit: REEF Technology

The COVID-19 outbreak that has changed so much of modern life in America so quickly in the span of a single year didn’t create the urge to transform the urban environment, but it did much to accelerate it.

As REEF acknowledges, cities are the future.

Roughly two-thirds of the world’s population will live in cities by 2050, and the world’s largest cities are cracking under the pressures of economic, civil, and environmental transformations that they have not been able to address effectively.

Mobility and, by extension, places to store and maintain those mobile technologies are part of the problem. Roughly half of the average modern American city, as REEF notes, is devoted to parking, while parks occupy only 10% of urban spaces. REEF’s language is centered on changing a world of parking lots into a space of paradises, but that language belies a reality that makes its money (at least for now) off of isolating individuals into personal spaces where their commercial needs are met by delivery — not by community interaction.

Still, the fact remains that something needs to change.

“Traditional developers and local policies have been slow to adopt new technologies and operating models,” said Stonly Baptiste, an investor in the transformation of urban environments through the fund, Urban.Us (which is not a backer of REEF). “But the demand is growing for a better ‘city product’, the need to make cities better for the environment and our lives has never been greater, and the dream to build the city of the future never dies. Not that dream is subsidized by VC.”

]]>