TechCrunch

TechCrunch

The European Data Protection Supervisor (EDPS), Wojciech Wiewiorówski, made the call for a ban on surveillance-based targeted ads in reference to the Commission’s Digital Services Act (DSA) — following a request for consultation from EU lawmakers.

The DSA legislative proposal was introduced in December, alongside the Digital Markets Act (DMA) — kicking off the EU’s (often lengthy) co-legislative process which involves debate and negotiations in the European Parliament and Council on amendments before any final text can be agreed for approval. This means battle lines are being drawn to try to influence the final shape of the biggest overhaul to pan-EU digital rules for decades — with everything to play for.

The intervention by Europe’s lead data protection supervisor calling for a ban on targeted ads is a powerful pre-emptive push against attempts to water down legislative protections for consumer interests.

The Commission had not gone so far in its proposal — but big tech lobbyists are certainly pushing in the opposite direction so the EDPS taking a strong line here looks important.

In his opinion on the DSA the EDPS writes that “additional safeguards” are needed to supplement risk mitigation measures proposed by the Commission — arguing that “certain activities in the context of online platforms present increasing risks not only for the rights of individuals, but for society as a whole”.

Online advertising, recommender systems and content moderation are the areas the EDPS is particularly concerned about.

“Given the multitude of risks associated with online targeted advertising, the EDPS urges the co-legislators to consider additional rules going beyond transparency,” he goes on. “Such measures should include a phase-out leading to a prohibition of targeted advertising on the basis of pervasive tracking, as well as restrictions in relation to the categories of data that can be processed for targeting purposes and the categories of data that may be disclosed to advertisers or third parties to enable or facilitate targeted advertising.”

It’s the latest regional salvo aimed at mass-surveillance-based targeted ads after the European Parliament called for tighter rules back in October — when it suggested EU lawmakers should consider a phased in ban.

Again, though, the EDPS is going a bit further here in actually calling for one. (Facebook’s Nick Clegg will be clutching his pearls.)

More recently, the CEO of European publishing giant Axel Springer, a long time co-conspirator of adtech interests, went public with a (rather protectionist-flavored) rant about US-based data-mining tech platforms turning citizens into “the marionettes of capitalist monopolies” — calling for EU lawmakers to extend regional privacy rules by prohibiting platforms from storing personal data and using it for commercial gain at all.

Apple CEO, Tim Cook, also took to the virtual stage of a (usually) Brussels based conference last month to urge Europe to double down on enforcement of its flagship General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

In the speech Cook warned that the adtech ‘data complex’ is fuelling a social catastrophe by driving the spread of disinformation as it works to profit off of mass manipulation. He went on to urge lawmakers on both sides of the pond to “send a universal, humanistic response to those who claim a right to users’ private information about what should not and will not be tolerated”. So it’s not just European companies (and institutions) calling for pro-privacy reform of adtech.

The iPhone maker is preparing to introduce stricter limits on tracking on its smartphones by making apps ask users for permission to track, instead of just grabbing their data — a move that’s naturally raised the hackles of the adtech sector, which relies on mass surveillance to power ‘relevant’ ads.

Hence the adtech industry has resorted to crying ‘antitrust‘ as a tactic to push competition regulators to block platform-level moves against its consentless surveillance. And on that front it’s notable than the EDPS’ opinion on the DMA, which proposes extra rules for intermediating platforms with the most market power, reiterates the vital links between competition, consumer protection and data protection law — saying these three are “inextricably linked policy areas in the context of the online platform economy”; and that there “should be a relationship of complementarity, not a relationship where one area replaces or enters into friction with another”.

Wiewiorówski also takes aim at recommender systems in his DSA opinion — saying these should not be based on profiling by default to ensure compliance with regional data protection rules (where privacy by design and default is supposed to be the legal default).

Here too be calls for additional measures to beef up the Commission’s legislative proposal — with the aim of “further promot[ing] transparency and user control”.

This is necessary because such system have “significant impact”, the EDPS argues.

The role of content recommendation engines in driving Internet users towards hateful and extremist points of view has long been a subject of public scrutiny. Back in 2017, for example, UK parliamentarians grilled a number of tech companies on the topic — raising concerns that AI-driven tools, engineered to maximize platform profit by increasing user engagement, risked automating radicalization, causing damage not just to the individuals who become hooked on hateful views the algorithms feeds them but cascading knock-on harms for all of us as societal cohesion is eaten away in the name of keeping the eyeballs busy.

Yet years on little information is available on how such algorithmic recommender systems work because the private companies that operate and profit off these AIs shield the workings as proprietary business secrets.

The Commission’s DSA proposal takes aim at this sort of secrecy as a bar to accountability — with its push for transparency obligations. The proposed obligations (in the initial draft) include requirements for platforms to provide “meaningful” criteria used to target ads; and explain the “main parameters” of their recommender algorithms; as well as requirements to foreground user controls (including at least one “nonprofiling” option).

However the EDPS wants regional lawmakers to go further in the service of protecting individuals from exploitation (and society as a whole from the toxic byproducts that flow from an industry based on harvesting personal data to manipulate people).

On content moderation, Wiewiorówski’s opinion stresses that this should “take place in accordance with the rule of law”. Though the Commission draft has favored leaving it with platforms to interpret the law.

“Given the already endemic monitoring of individuals’ behaviour, particularly in the context of online platforms, the DSA should delineate when efforts to combat ‘illegal content’ legitimise the use of automated means to detect, identify and address illegal content,” he writes, in what looks like a tacit recognition of recent CJEU jurisprudence in this area.

“Profiling for purposes of content moderation should be prohibited unless the provider can demonstrate that such measures are strictly necessary to address the systemic risks explicitly identified by the DSA,” he adds.

The EDPS has also suggested minimum interoperability requirements for very large platforms, and for those designated as ‘gatekeepers’ (under the DMA), and urges lawmakers to work to promote the development of technical standards to help with this at the European level.

On the DMA, he also urges amendments to ensure the proposal “complements the GDPR effectively”, as he puts it, calling for “increasing protection for the fundamental rights and freedoms of the persons concerned, and avoiding frictions with current data protection rules”.

Among the EDPS’ specific recommendations are: That the DMA makes it clear that gatekeeper platforms must provide users with easier and more accessible consent management; clarification to the scope of data portability envisaged in the draft; and rewording of a provision that requires gatekeepers to provide other businesses with access to aggregated user data — again with an eye on ensuring “full consistency with the GDPR”.

The opinion also raises the issue of the need for “effective anonymisation” — with the EDPS calling for “re-identification tests when sharing query, click and view data in relation to free and paid search generated by end users on online search engines of the gatekeeper”.

ePrivacy reform emerges from stasis

Wiewiorówski’s contributions to shaping incoming platform regulations come on the same day that the European Council has finally reached agreement on its negotiating position for a long-delayed EU reform effort around existing ePrivacy rules.

In a press release announcing the development, the Commission writes that Member States agreed on a negotiating mandate for revised rules on the protection of privacy and confidentiality in the use of electronic communications services.

“These updated ‘ePrivacy’ rules will define cases in which service providers are allowed to process electronic communications data or have access to data stored on end-users’ devices,” it writes, adding: “Today’s agreement allows the Portuguese presidency to start talks with the European Parliament on the final text.”

Reform of the ePrivacy directive has been stalled for years as conflicting interests locked horns — putting paid to the (prior) Commission’s hopes that the whole effort could be done and dusted in 2018. (The original ePrivacy reform proposal came out in January 2017; four years later the Council has finally settled on its arguing mandate.)

The fact that the GDPR was passed first appears to have upped the stakes for data-hungry ePrivacy lobbyists — in both the adtech and telco space (the latter having a keen interest in removing existing regulatory barriers on comms data in order that it can exploit the vast troves of user data which Internet giants running rival messaging and VoIP services have long been able to).

There’s a concerted effort to try to use ePrivacy to undo consumer protections baked into GDPR — including attempts to water down protections provided for sensitive personal data. So the stage is set for an ugly rights battle as negotiations kick off with the European Parliament.

Metadata and cookie consent rules are also bound up with ePrivacy so there’s all sorts of messy and contested issues on the table here.

Digital rights advocacy group Access Now summed up the ePrivacy development by slamming the Council for “hugely” missing the mark.

“The reform is supposed to strengthen privacy rights in the EU [but] States poked so many holes into the proposal that it now looks like French Gruyère,” said Estelle Massé, senior policy analyst at Access Now, in a statement. “The text adopted today is below par when compared to the Parliament’s text and previous versions of government positions. We lost forward-looking provisions for the protection of privacy while several surveillance measures have been added.”

The group said it will be pushing to restore requirements for service providers to protect online users’ privacy by default and for the establishment of clear rules against online tracking beyond cookies, among other policy preferences.

The Council, meanwhile, appears to be advocating for a highly dilute (and so probably useless) flavor of ‘do not track’ — by suggesting users should be able to give consent to the use of “certain types of cookies by whitelisting one or several providers in their browser settings”, per the Commission.

“Software providers will be encouraged to make it easy for users to set up and amend whitelists on their browsers and withdraw consent at any moment,” it adds in its press release.

Clearly the devil will be in the detail of the Council’s position there. (The European Parliament has, by contrast, previously clearly endorsed a “legally binding and enforceable” Do Not Track mechanism for ePrivacy so, again, the stage is set for clashes.)

Encryption is another likely bone of ePrivacy contention.

As security and privacy researcher, Dr Lukasz Olejnik, noted back in mid 2017, the parliament strongly backed end-to-end encryption as a means of protecting the confidentiality of comms data — saying then that Member States should not impose any obligations on service providers to weaken strong encryption.

So it’s notable that the Council does not have much to say about e2e encryption — at least in the PR version of its public position. (A line in this that runs: “As a main rule, electronic communications data will be confidential. Any interference, including listening to, monitoring and processing of data by anyone other than the end-user will be prohibited, except when permitted by the ePrivacy regulation” is hardly reassuring, either.)

It certainly looks like a worrying omission given recent efforts at the Council level to advocate for ‘lawful’ access to encrypted data. Digital and humans rights groups will be buckling up for a fight.

]]>

TechCrunch

TechCrunch

Last year, in the midst of a particularly spiky U.S. presidential election campaign, a startup called Sentropy emerged from stealth with an AI-based platform aimed at social media and other companies that corralled people together for online conversation.

Sentropy had built a set of algorithms, using natural language processing and machine learning, to help these platforms detect when abusive language, harassing tendencies and other harmful content was coming around the bend, and to act on those situations before they became an issue.

Today, the startup is unveiling a new product, now aimed at consumers.

Using the same technology that it originally built for its enterprise platform, Sentropy Protect is a free consumer product that detects harmful content on a person’s social media feed and, by way of a dashboard, lets a person have better control over how that content and the people producing it are handled.

Starting initially with Twitter, the plan is to add more social feeds over time, based initially on which services provide APIs to let Sentropy integrate with them (not all do.)

Sentropy CEO John Redgrave said the consumer product launch is not a pivot but an expansion of what the company is building.

The idea is that Sentropy will continue to work with enterprise customers — its two products in that department are called Sentropy Detect, which provides API-based access to its abuse detection technologies; and Sentropy Defend, a browser-based interface that enables end-to-end moderation workflows for moderators.

But at the same time, the Protect consumer product will give people an added option — whether or not Sentropy is being used by a particular platform — to take the reins and have more hands-on control over their harassment graph, as it were.

“We always had deep conviction of going after the enterprise as a start, but Sentropy is about more than that,” he said. “Cyber safety has to have both enterprise and consumer components.”

It’s refreshing to hear about startups building services that potentially affect millions of people also being cognizant of how individuals themselves want to keep an element of self-determination in the equation.

It’s not just, “Well, it’s your choice if you use service X or not,” but a grasp of the concept that when someone chooses to use a service, especially a popular one, there should be and can be more than just a hope that the platform will always be looking out for that user’s best interests, by providing tools to help the user do that, too.

And it’s not a problem that is going away, and that goes not just for the hottest platforms today, which are continuing to look for ways to handle complex content — but also on emerging platforms.

The recent popularity of Clubhouse, for example, highlights not just new frontiers in social platforms, but how, for example, those new models — with Clubhouse based on “rooms” for conversations and a reliance on audio rather than written text for interactions — are handling issues of harassment and abuse. Some striking examples so far point to the problem being one that definitely needs addressing before it grows any bigger.

Protect is free to use today, and Redgrave said that Sentropy is still working on deciding how and if it will charge for it. One likely scenario will be that Protect might come in freemium tiers: a free and limited product for individuals with “pro” services featuring enhanced tools, and perhaps a tier for companies who are managing accounts on behalf of one or several high-profile individuals.

Of course, services like Twitter, Reddit, Facebook, YouTube and many others have made a big point over the years — and especially recently — to put in more rules, moderators and automated algorithms to help identify and stop abusive content in its tracks, and to help users report and stop content before it gets to them.

But if you are one of the people who gets targeted regularly, or even occasionally, you know that this is often not enough. Sentropy Protect seems to be built with that mindset in mind, too.

Indeed, Redgrave said that even though the company had consumers on its roadmap all along, its strategy was accelerated after the launch of its enterprise product last year in June.

“We started getting pinged by people saying, ‘I get abused online. How can I get access to your technology?’” He recalled that the company realized that the problem was at once bigger and more granular than Sentropy could fix simply by working its way through a list of companies, hoping to win them over as customers, and then successfully integrating its product.

“We had a hard decision to make then,” he recalled. “Do we spend 100% of our time focused on enterprises, or do we take a portion of our team and start to build out something for consumers, too?” It decided to take the latter route.

On the enterprise side, Sentropy is continuing to work with social networks and other kinds of companies that host interactions between people — for example, message boards connected to gaming experiences or dating apps. It’s not publicly disclosing any customer names at the moment, but Redgrave describes them as primarily smaller, fast-growing businesses, as opposed to larger and more legacy platforms.

Sentropy’s VP of product, Dev Bala — who has previously been an academic, and also worked at Facebook, Google and Microsoft — explained that bigger, legacy platforms are not outside of Sentropy’s remit. But more often than not, they are working on bigger trust and safety strategies and have small armies of engineers in-house working on building products.

While larger social networks do bring in third-party technology for certain aspects of their services, those deals will typically take longer to close, even in urgent cases such as around working with online abuse.

“I think abuse and harassment are rapidly evolving to be an existential challenge for the likes of Facebook, Reddit, YouTube and the rest,” Bala said. “These companies will have a 10,000 person organization thinking just about trust and safety, and the world is seeing the ills of not doing that. What’s not as obvious to people on the outside is that they are also taking a portfolio approach, with armies of moderators and a portfolio of technology. Not all is built in-house.

“We believe there is value from Sentropy for these bigger guys but also know there are a lot of optics around companies using products like ours. So we see the opportunities of going earlier, in cases where the company in question is not a Facebook, and having a less sophisticated approach.”

As a sign of the changing tides and sentiment in the market. It seems that the tackling of abuse and content is starting to get taken seriously as a business concept. And so Sentropy is not the only company tackling this opportunity.

Two other startups — one called Spectrum Labs, and another called L1ght — have also built a set of AI-based tools aimed at various platforms where conversations are happening to help those platforms detect and better moderate instances of toxicity, harassment and abuse.

Another, Block Party, is also looking to work across different social platforms to give users more control over how toxicity touches them, and has, like Sentropy, focused first on Twitter.

With Protect, after content is detected and flagged, users can set up wider, permanent blocks against specific users (who can also be muted through Protect) or themes, manage filtered words, and monitor content that gets automatically flagged for being potentially abusive, in case you want to override the flags and create “trusted” users. Tweets get labelled when they are snagged by Sentropy by the type of abuse (for example, threat of physical violence, sexual aggression or identity attacks).

Since it’s based on a machine-learning platform, Sentropy then takes all of those signals, including the tweets that have been flagged and uses them to teach Protect to identify future content along those same lines. The platform is also monitoring chatter on other platforms all the time, and that too feeds into what it looks for and moderates.

If you’re familiar with Twitter’s own abuse protection, you’ll know that all this takes the situation several steps further than the controls Twitter itself provides.

This is still a version one though. Right now, you don’t see your full timeline through Protect, so essentially it means that you toggle between Protect and whatever Twitter client you are using. Some might find that onerous, although on the other hand Bala noted that a sign of Sentropy’s success is that people will actually let it work in the background and you won’t feel the need to constantly check in.

Redgrave also noted that the service is still exploring how to add in other features, such as the ability to also filter direct messages.

]]>

TechCrunch

TechCrunch

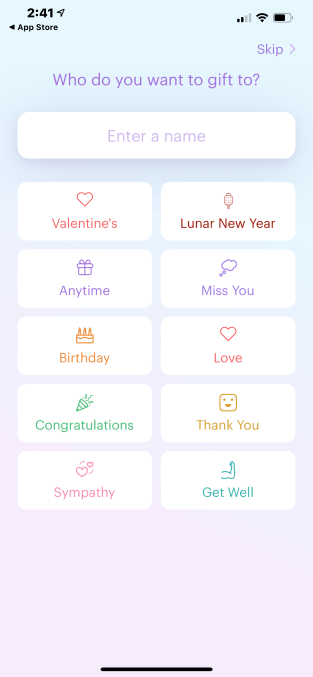

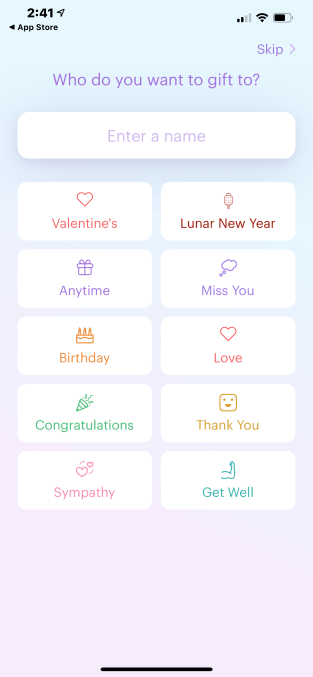

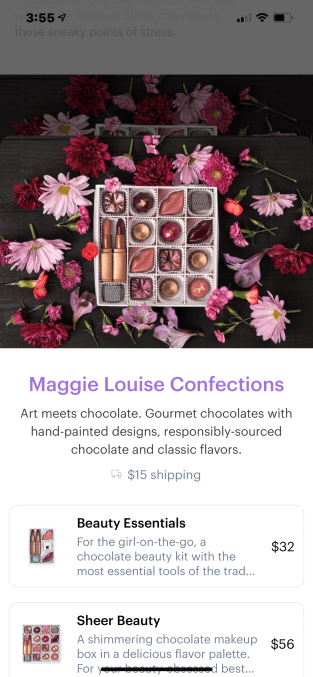

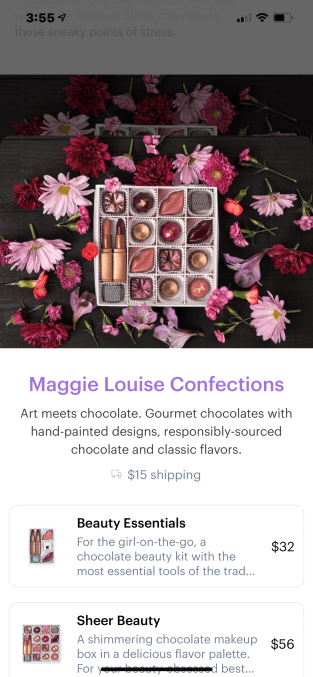

To do so, you first download the Goody mobile app for iOS or Android, then browse across the hundreds of brands and products it offers. You also can filter these by occasion, like birthdays or holidays, or by a specific need, such as gifts to say congratulations or get well.

Image Credits: Goody

When you find a gift you like, you just enter the recipient’s phone number. Goody then sends a text that lets the recipient know that you’ve sent them something. The recipient clicks the link to accept the gift, which opens a website where they can see what you’ve selected, while also customizing any specific options — like their clothing size, color preferences or what flavor of cupcakes they’d like, for example.

Here, they also provide their shipping address, and the gift is sent. Afterwards, they can choose to send a thank you note, as well.

What makes this experience work is that — unlike some gifting startups in the past — Goody doesn’t require the recipient to download an app, nor do you need to know anything other than a phone number of the person you want to send a gift to.

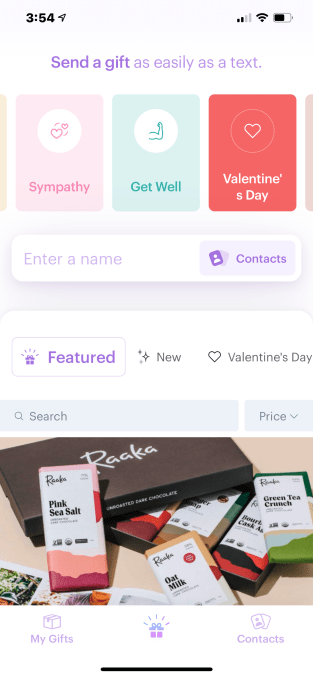

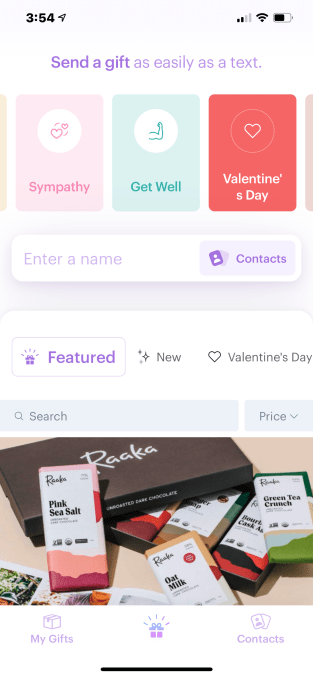

Image Credits: Goody

The idea for Goody comes from co-founder and serial entrepreneur and startup investor Edward Lando, whose prior company, YC-backed GovPredict, was recently acquired. He was also the first investor in Misfits Market, serves on the board at Atom Finance and is a managing partner at Pareto Holdings, based in Miami, where Lando now lives.

Joining him on Goody are Even.com tech lead Mark Bao and Lee Linden, who notably sold his prior gifting startup Karma Gifts to Facebook back in 2012.

Lando says he was interested in working on the idea because he loves to send gifts, but thinks there’s a lot of friction involved with the process as it stands today. Meanwhile, gifts that are easier to send, like gift cards, can lack a personal touch.

“The most important thing for us is for Goody to feel highly personal,” Lando explains. “If someone sends you something through Goody [it should feel like], wow, they really thought about me — they picked out something for me. We don’t want it to feel like someone is just sending you a dollar value,” he says.

The mobile app launched in mid-December and now works with a couple dozen brand partners. Many of these are in the direct-to-consumer space or are otherwise emerging companies, like non-alcoholic aperitif Ghia, workout experience The Class, pet company Fable, wellness company Moon Juice, Raaka Chocolate and others.

Image Credits: Goody

Goody’s model involves a revenue share with its partners, where its cut increases the more sales its makes on the partner’s behalf.

Brands are interested in working with Goody, Lando explains, because it can help them acquire new customers with little effort on their part.

“There’s so many direct-to-consumer brands these days — thousands of them — selling online — coffee, chocolate, all these cool things,” Lando says. “And for now, their only way of getting discovered is buying ads on Facebook. We’re another way for people to discover them. We’re like a giant shopping mall for people to discover these things,” he adds.

The app, however, wants to be useful to those who also just want to stay in touch with friends and family. On this front, it’s rolling out free gifts this week called “IOUs,” for telling someone you’re thinking of them — for example, by saying something like “I owe you dinner next time I’m in town” or sharing some other more symbolic gift.

The app will also later integrate a calendar that will help you track important occasions, like birthdays and other major life events.

Goody was founded in March 2020 and the app launched in mid-December of the same year. So far, around 10,000 gifts have been sent using its service, Lando says.

In addition to the holiday season, of course, the pandemic may have played a role in Goody’s early traction.

“I think the pandemic has been a big problem for everyone. And one of the things that people frankly don’t talk about enough, in my opinion, is the psychological toll the pandemic is taking on everyone…we are all creatures that enjoy social interaction. It feels good to see other people — especially the people you care about. And when you don’t, it really drains you of energy,” Lando says.

“This is obviously not the same as seeing people in person, but I do think that Goody is a nice injection of warmth and positivity…Everyone who uses it says they feel good after using it, which I think is rare,” Lando notes.

Image Credits: Goody ad in NYC

The startup, meanwhile, has raised a little more than $4 million in early funding from investors including Quiet Capital, Index Ventures, Pareto Holdings, Third Kind Venture Capital, Craft Ventures and the founders of Coinbase (Fred Ehrsam) and Quora (Charlie Cheever), among others.

Goody is a team of nine full-time employees, based in Miami and elsewhere, working remotely. Ahead of Valentine’s Day, the company snagged a spot on a Times Square billboard to advertise its app, in the hopes of gaining new users during one of the bigger gifting holidays of the year.

The app is available as a free download on the App Store and Google Play.

]]>