TechCrunch

TechCrunch

Stream, which lets developers build chat and activity streams into apps and other services by way of a few lines of code, has raised $38 million, funding that it will be using to continue building out its existing business as well as to work on new features.

Stream started out with APIs for activity feeds, and then it expanded to chat, which today can be integrated into apps built on a variety of platforms. Currently, its customers integrate third-party chatbots and use Dolby for video and audio within Stream, but over time, these are all areas where Stream itself would like to do more.

“End-to-end encryption, chatbots: We want to take as many components as we can,” said Thierry Schellenbach, the CEO who co-founded the startup with the startup’s CTO Tommaso Barbugli in Amsterdam in 2015 (the startup still has a substantial team in Amsterdam headed by Barbugli, but its headquarters is now in Boulder, Colorado, where Schellenbach eventually moved).

The company already has amassed a list of notable customers, including Ikea-owned TaskRabbit, NBC Sports, Unilever, Delivery Hero, Gojek, eToro and Stanford University, as well as a number of others that it’s not disclosing across healthcare, education, finance, virtual events, dating, gaming and social. Together, the apps Stream powers cover more than 1 billion users.

This Series B round is being led by Felicis Ventures’ Aydin Senkut, with previous backers GGV Capital and 01 Advisors (the fund co-founded by Twitter’s former CEO and COO, Dick Costolo and Adam Bain) also participating.

Alongside them, a mix of previous and new individual and smaller investors also participated: Olivier Pomel, CEO of Datadog; Tom Preston-Werner, co-founder of GitHub; Amsterdam-based Knight Capital; Johnny Boufarhat, founder and CEO of Hopin; and Selcuk Atli, co-founder and CEO of social gaming app Bunch (itself having raised a notable round of $20 million led by General Catalyst not long ago).

That list is a notable indicator of what kinds of startups are also quietly working with Stream.

The company is not disclosing its valuation but said chat revenue grew by 500% in 2020.

Indeed, the Series B speaks of a moment of opportunity: It is coming only about six months after the startup raised a Series A of $15 million, and in fact Stream wasn’t looking to raise right now.

“We were not planning to raise funding until later this year but then Aydin reached out to us and made it hard to say no,” Schellenbach said.

“More than anything else, they are building on the platforms in the tech that matters,” Senkut added in an interview, noting that its users were attesting to a strong return on investment. “It’s rare to see a product so critical to customers and scaling well. It’s just uncapped capability… and we want to be a part of the story.”

That moment of opportunity is not one that Stream is pursuing on its own.

Some of the more significant of the many players in the world of API-based communications services like messaging, activity streams — those consolidated updates you get in apps that tell you when people have responded to a post of yours or new content has landed that is relevant to you, or that you have a message, and so on — and chat include SendBird, Agora, PubNub, Twilio and Sinch, all of which have variously raised substantial funding, found a lot of traction with customers, or are positioning themselves as consolidators.

That may speak of competition, but it also points to the vast market there for the tapping.

Indeed, one of the reasons companies like Stream are doing so well right now is because of what they have built and the market demand for it.

Communications services like Stream’s might be best compared to what companies like Adyen (another major tech force out of Amsterdam), Stripe, Rapyd, Mambu and others are doing in the world of fintech.

As with something like payments, the mechanics of building, for example, chat functionality can be complex, usually requiring the knitting together of an array of services and platforms that do not naturally speak to each other.

At the same time, something like an activity feed or a messaging feature is central to how a lot of apps work, even if they are not the core feature of the product itself. One good example of how that works are food ordering and delivery apps: they are not by their nature “chat apps” but they need to have a chat option in them for when you do need to communicate with a driver or a restaurant.

Putting those forces together, it’s pretty logical that we’d see the emergence of a range of tech companies that both have done the hard work of building the mechanics of, say, a chat service, and making that accessible by way of an API to those who want to use it, with APIs being one of the more central and standard building blocks in apps today; and a surge of developers keen to get their hands on those APIs to build that functionality into their apps.

What Stream is working on is not to be confused with the customer-service focused services that companies like Zendesk or Intercom are building when they talk about chat for apps. Those can be specialized features in themselves that link in with CRM systems and customer services teams and other products for marketing analytics and so on. Instead, Stream’s focus are services for consumers to talk to other consumers.

What is a trend worth watching is whether easy-to-integrate services like Stream’s might signal the proliferation of more social apps over time.

There is already at least one key customer — which I am now allowed to name — that is a steadily growing, still young social app, which has built the core of its service on Stream’s API.

With just a handful of companies — led by Facebook, but also including ByteDance/TikTok, Tencent, Twitter, Snap, Google (via YouTube) and some others depending on the region — holding an outsized grip on social interactions, easier, platform-agnostic access to core communications tools like chat could potentially help more of these, with different takes on “social” business models, find their way into the world.

“Stream’s technology addresses a common problem in product development by offering an easy-to-integrate and scalable messaging solution,” said Dick Costolo of 01 Advisors, and the former Twitter CEO, in a statement. “Beyond that, their team and clear vision set them apart, and we ardently back their mission.”

Updated to correct that the revenue growth is not related to the valuation figure.

]]>

TechCrunch

TechCrunch

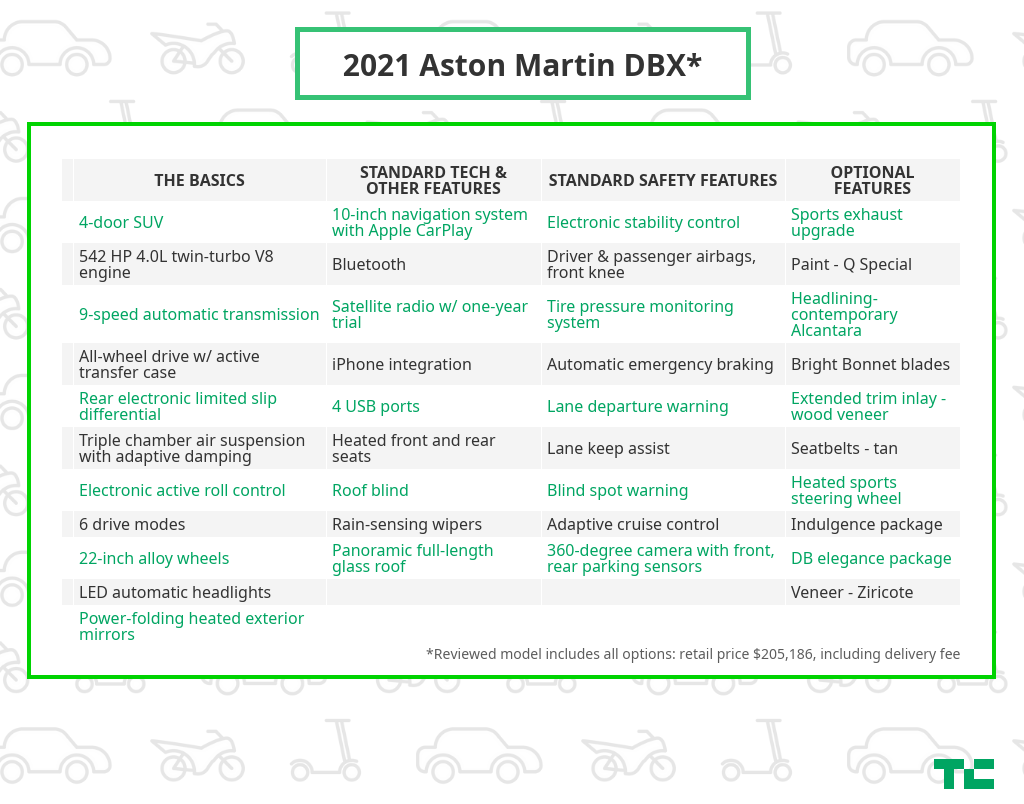

Like Astons before it, the DBX is objectively handsome. Its sculptural form stretches out to unapologetic ample proportions, and stands out in the crowd of SUVs that frequent the private-school pickup lane. It’s an opulent design that scores high on aesthetics, performance and character. It’s also a vehicle that arrives late to the ultra premium SUV segment, and lacks the in-car technology and fuel economy of others of its ilk. Sales of the DBX, which starts at $176,900, began overseas last summer and entered the U.S. market in late 2020. (The version Aston Martin provided to TechCrunch for a test drive had the option-loaded retail price of $205,186 DBX, including delivery fees.)

Call it a tale of two vehicles in a time of dueling principles vying for luxury auto buyer budgets. Demand for SUVs continues to skyrocket, just as the mobility sector inclines sharply toward electrification. Aston Martin set a goal of selling 14,000 vehicles by 2023, a steep hike for a small, boutique brand. However, under new leadership, the company has dialed back those projections to 10,000 as part of its reorganization dubbed “Project Horizon.”

After an underwhelming year due to the pandemic, a new major owner and a new CEO are in place. It’s unclear which narrative will determine the DBX’s fate. The future of the company rests on its success.

Aston Martin said the DBX met sales expectations in 2020, with 1,516 units sold. The company anticipates that the DBX will make up 40% to 60% of global volume in 2021 — its first year of full production.

A tale of two vehicles

How to achieve best-in-class tech in both engineering and in-car experience is a quagmire for low-volume supercar makers who aren’t owned by a larger automaker that can lend that expertise. Aston took steps to solve this problem through an agreement reached with Mercedes-Benz AG to develop engines and electric architecture back in 2013. Tobias Moers, who headed up Mercedes-Benz’s AMG division until last summer, is Aston’s new CEO, a clue on how vital Aston still sees Daimler’s technical performance to its future.

Aston Martin has recently reentered Formula One racing, and true to the brand’s motorsports history, the DBX has sports car-like power, sprinting from 0 to 60 miles per hour in 4.3 seconds, using Mercedes-Benz AMG engines.

On the interior, the DBX scores high as a total sensory experience to drive (and floss in), affording its passengers panache and comfort, all swathed in Bridge of Weir leather. There are nifty options such as a snow pack, complete with a ski boot warmer.

Image Credits: Aston Martin

The other half of this product’s interior story raises more pragmatic questions about the role of in-car tech in the super luxury segment, and gets at the crux of Aston’s dilemma. Aston will always be at least one generation behind the latest Mercedes advancements. For a vehicle with a starting price of $180,000, cars that cost half the price have more advanced in-car features.

User experience

The Aston Martin DBX is equipped with COMAND, an infotainment system that Mercedes introduced in 1998, refreshed in 2014 and updated again in 2016. When it comes to tech, a few years feels like a lifetime.

The challenge is that it’s not as simple as replacing a head-unit, Nathan Hoyt, a spokesperson for Aston Martin, told TechCrunch.

“The car would need to be revised to work a whole new electrical architecture” he said. “That said, the closer alignment we previously announced between Mercedes and Aston Martin means we will continue using MB technology for the foreseeable future.”

While Aston Martin is saddled with an older system, Mercedes-Benz has since moved on to MBUX, a new more technologically advanced infotainment system that was introduced in 2018 and has already been updated. No word on when MBUX will find its way to Aston Martin products.

In practical terms, that means a 2021 luxury vehicle that’s missing a touchscreen. What’s in its place is far too much clunky plastic to be called classic analog, which perhaps would make more sense. Think Mac keyboard, circa 2014. Apple CarPlay is standard on the DBX, but it lacks Android Auto.

Instead of slick knobs, there are plastic buttons that seem out of step with the rest of the vehicle’s swanky naturally sourced woods. Plastic is also present on the air vents and gear selector.

In fairness, the everything-but-the-kitchen sink isn’t the best solution to in-car technology. Many carmakers have far too much frustrating and tactile tech on the dash that isn’t intuitive.

The tech that stood out

Aston’s done what it can to make DBX’s inner working distinct from the traditional Mercedes system. Creative thinking shows up in the 10.2-inch display’s slick graphics made for DBX on the center stack. A DB5, James Bond’s vehicle of choice, is used as an icon to indicate adaptive cruise control activation.

Aston manages to use the tech that it does have to its advantage — and it’s a whole mood.

Ambient lighting offers 64 different colors in two zones and a sound system that feels of the moment. The custom sound system boasts 790 watts over 13 speakers and a sealed subwoofer, and noise compensation tech that drowns out road noise. The combination of that cushy cabin and the boom of those speakers makes it feel as if one is driving around in a high-end theater, back when we all went to the movies, or if you’re an Aston owner, escaped into your personal home theater.

ADAS: form and function

Aston compensates for lack of computational power by making adaptive cruise control, front and rear parking sensors, lane-departure warning, lane-keeping assist and blind-spot monitoring all standard safety features.

Each function is housed in one of the aforementioned plastic buttons. Adaptive cruise control is on the left of the steering wheel, and can be adjusted to monitor distance and speed. The lane-keeping assist button is on the right of the center console.

The controls on the center console require the driver to glance down for a brief moment, causing the eyes to flit off the road. When lane-keeping assist is engaged, a light on the dash and a gentle twitch of the wheel alert the driver. Other switches control driver performance and Aston’s air suspension settings.

Character study

Stateside, Aston might be limited to James Bond, but for the British car culture enthusiasts, the brand is steeped in emotion, gravitas and significance. I attended the Aston centenary in 2010 in England, where I saw an outpouring of love across the U.K. for the brand’s heritage.

Under former CEO Andy Palmer, Aston was in pursuit of its future. A more modern factory in Wales was built to make DBX. But part of Aston’s intrinsic appeal is that some components are still hand built to suit the low-volume connoisseur of a few thousand-of-a-kind vehicle. As cars become more complex computerized systems, hand built becomes more of a liability.

The DBX’s path comes down to what the prospective driver wants and needs this vehicle to be in place of proper high-six figure dream machine such as the Rolls-Royce Cullinan owned by the BMW group, or Bentley Bentayga, Lamborghini Urus and Porsche Cayenne, which fall under the collective VW umbrella. Or Tesla, which is Tesla.

As slick technological features become more important, Aston Martin may need to rethink how it solves for lagging behind. That may mean doubling down on what it means to be unapologetic and classic. Or using future powertrain variants to push the 21st century automaker messaging. The latter seems most likely.

A 2020 agreement with Mercedes that builds off of an existing partnership will give Aston Martin access to a wide range of technology, including electric, mild and full hybrid powertrain architectures through 2027.

Aston Martin indicated in its latest earnings call that offering a hybrid SUV will be important for the company. Tobias Moers, Aston Martin’s new CEO and the former head of Mercedes-Benz AMG, said a plug-in hybrid DBX will be offered before 2024. All-electric vehicles are part of the company’s plans as well, and have been targeted for middle of the decade.

The question is whether Aston Martin will give the infotainment system the needed upgrade to match the hybrid and EV tech.

When it comes to high-six figure SUVs, the air is thin at the top.

]]>

TechCrunch

TechCrunch

Those marketplaces, along with others, are where people go to buy digital assets, or, non-fungible tokens (NFTs) that live on the blockchain. This whole world of NFTs is super new to me (I’ve only been using Top Shot for a couple of weeks now) so I caught up with a couple of NFT creators to break it down for me, as well as share some insights on where they think the space is going, and it’s overall potential.

“The way I like to explain NFTs, they are digital assets with true ownership and provenance,” Ronin the Collector told TechCrunch. “You can track their origin and they can only be owned by one person.”

Many people, myself included, at some point wonder why someone would pay for a short video clip of, for example, Stephen Curry making a three-pointer when you download it to your computer for free.

“Humans inherently, whether we will like to admit it or not, want to own things,” Ronin said. “And I think that that’s part of the human experience is owning things. When you own things, it’s a connection, and it’s like you have reason for being and there’s something unique about ownership. And I think that at the end of the day, yeah, you can you can watch it all you want. But can you sell it?”

With that clip as an NFT, you can. As an example, one user bought a LeBron James dunk for $208,000 a couple of weeks ago, according to CryptoSlam. Last month, Top Shot reached nearly $50 million in marketplace transactions. Then, over a 24-hour period last week, Top Shot saw more than $37 million in sales, according to Cryptoslam.

As to why they’re blowing up right now, Ronin attributes it to a couple of things: the pandemic that’s forced everyone behind a computer screen and an easy entry point. Top Shot, for example, makes it super easy for plebeians like me to sign up and you don’t need to have a crypto wallet. You can just use your credit card. The same goes for Nifty Gateway.

But Top Shot and Nifty are outliers, Ronin said. For the majority of NFT platforms, you need to have an Ethereum wallet. As Cooper Turley, crypto strategy lead at Audius, wrote on TC, “this means collectors need to purchase ETH from an exchange like Coinbase and send it to a non-custodial address that consists of a long string of numbers and letters to get started.”

That sounds like a whole thing that I, for one, am not ready to dive into. In general, barriers to access continue to be a problem in the NFTs space, Ronin said.

“Projects are just now starting to pay attention to the user experience,” he said. “And just barely in time. One of the best rooms I’ve been on Clubhouse was one that talked about how basically, with the whole world watching, how do we not mess this up. So I think when you have a product like Top Shot, which is easy to get into, easy to sign up for, and easy to purchase. You have to use a credit card, you don’t need crypto and throw in the mix that everyone’s online and then Beeple sells $3 million worth of digital art, and all of a sudden, people want to pay attention. So I think that was the catalyst.”

But an even more expansive and interesting arena for NFTs than Top Shot is the world of NFT art. Ameer Carter, an artist that is also known as Sirsu, got into NFTs last summer thanks to a friend, he told TechCrunch. Pretty much immediately, he said, he realized the transformative nature of the technology.

“We literally have creative immortality,” he told me he realized at the time.

But the art world has historically been inhospitable to Black folks and people of color, and especially in the world of NFTs, Carter said. The traditional art scene, Carter said, is elitist. And while Carter himself is a classically trained artist, he hasn’t been able to make his way into the traditional art world, he said.

“And it’s not because of lack of trying,” he said.

Carter said he’s had a number of conversations with art curators who all love his work, but they’ve told him it’s not “something that they could build a whole curriculum around and intellectualize,” he said. What NFTs do is enable artists like Carter to create and share their art in a way that hadn’t previously been afforded to them.

“And this is a much more open and accessible platform, and environment for them to do so,” Carter said. “And so my goal is to help really give them that type of visibility and empower them to be creatives. My mission is to remove the starving artists stigma. I don’t believe that creativity is cheap. I believe that it is rich. And it enriches and it gives us the reasons why we live in the first place.”

However, Carter said he’s begun to notice white folks taking credit for things Black artists have already done.

“There’s this push and pull between folks who are really about the provenance of the blockchain versus folks who are wanting to predispose themselves as first because they have more visibility,” Carter said.

He pointed to Black artists like Connie Digital, Harrison First and others who were some of the first people to institute social tokens for their fans on the blockchain.

“They were some of the first to deploy and sell albums as NFTs, EPs as NFTs, singular songs,” Carter said. “And now we have Blau that came out and people were saying he’s the first to sell an album. And it’s like, well, that’s not true, technically. But what works and has continued to work is because there’s a lot of hoopla and a lot of money around that sale, that becomes the formative thing as being first because it’s the one that’s made the most noise. And I find it interesting because of the fact that we can literally go back tangibly, and there’s verifiable hash proof that it wasn’t the case.”

These are the types of phenomena pushing Carter to become an NFT archivist of sorts, he said.

“I’m not necessarily a historian, but I think the more and more I get involved in this space, the more and more I feel that pressing role of being an archivist,” he said. “So that culturally, we aren’t erased, even in a space that’s supposed to be decentralized and supposed to be something that works for everyone.”

That’s partly why Carter is building The Well to archive the work of Black artists, like Blacksneakers, for example. The Well will also be a platform for Black artists to mint their NFTs in a place that feels safe, supportive and not exploitative, he said.

On current platforms, Carter said it feels like white artists generally get more promotions on the site, as well as on social media, than Black artists.

“They deserve to have that kind of artists’ growth and development,” Carter said. “Yet it is afforded to a lot of other artists that don’t look like them.”

Carter said he recognizes it’s not the responsibility of platforms like Nifty Gateway, SuperRare and others to provide opportunities to Black artists, but that they do have the ability to put Black artists in a better position to receive opportunities.

That’s partly what Carter hopes to achieve with The Well Protocol. The Well, which Carter plans to launch on Juneteenth, aims to create an inclusive platform and ecosystem for NFT artists, collectors and curators. Carter said he wants artists to not have to feel like they have to constantly leverage Twitter to showcase their work. Instead, they’ll have the full backing of an ecosystem pumping up their work.

“Everywhere else, you look at other artists and they have write-ups, and they have news coverage and things of that nature,” Carter said. “And [Black artists] don’t have a lot of those avenues to compete. You know, I’m in the business of building true equity for us, so part and parcel to that is developing the tools and the ecosystem for us to thrive.”

No longer should art just be for the rich, Carter said.

“We have the ability to completely dismantle that,” he said. “So we have to be very, very, very careful about that and make a concerted effort to make that thing work, but we can’t do it when we have folks entering the space with money erasing folks who were already here. We can’t have that where platforms are not allowing the positioning of artists to grow. You know, we can’t have that when we have folks by and large, fear mongering and trying to get other artists to not be a part of this system.”

It’s also important, he said, for NFTs to not solely be seen as collectible, investable objects.

“Everyone’s getting into the game like it’s a money grab,” he said. “It’s not. It’s playing with artists lives and careers here.”

For those who aren’t yet in on NFTs, there’s still time, Ronin said. Even with the increased attention on NFTs, Ronin says it’s still early days.

“Honestly, I don’t even think we’ve got a full foot into early adoption yet,” he said. “I don’t think you come out of early adoption until we’ve got a solid experience across the board. I think we’re still in alpha.”

That’s partly because Ronin believes the things people will be able to do in five or ten years with this technology will pale in comparison to what’s happening today. For example, Ronin said he spoke with an artist who is experimenting with an NFT experience that will transcend VR, AR and XR.

“And I’m so excited that she chose to work with me and bring me in on this, and use me as kind of an advisor,” he said. “And she can change the world with this technology.”

That’s really what’s so exciting about NFTs for Ronin — the notion that the technology can change your life, and the world, he said.

“And it is a space in which you should feel free to come into and dream big and then figure out how to make those dreams happen,” he said. “You can use AR, VR, mobile, you know, the internet — you can use all these aspects and create an NFT experience that transcends space, transcends time, transcends our life. So it’s a super powerful technology. And I think that people should really pay attention.”

Down the road, Ronin also envisions having connected blockchains “where you can take an NFT from, you know, Bitcoin to Ethereum to WAX to Flow,” he said. “I really think that it’s why this this is that important.”

For Carter, he hopes his work at The Well will help to set a precedent for inclusivity and access in the NFT space. It’s worth mentioning that Carter is also working on the Mint Fund to help minimize the barriers to entry for artists looking to mint their first NFTs. Minting an NFT can be expensive to the tune of $50-$250 depending on how busy the Ethereum network is, and Mint Fund will pay those fees for new artists, making the on-ramp into the world smoother.

“If we don’t do this the right way with the right type of community-driven thinking, then we will lose,” he said. “And it’s not going to look good, it’s going to be ugly. And it’s going to again perpetuate the rich getting richer and the poor getting poorer…We have to find the best ways to redistribute wealth at any given point in time within this economy, within this system. If we do not know how to do that, we are fucked. At least in my opinion.”

There are also conversations in the space around the ecological impact of minting NFTs, which requires a good amount of energy to do. Carter described the existence of two camps: the camp arguing minting NFTs are very ecologically damaging and the ones saying it’s not the fault of minters and you can’t blame them “for minting on a system that is already going to process these transactions, whether they mint or not.”

For Carter, he thinks the first camp could be right, but says there’s just a lot of yelling at this point.

“I think that collectively, us as minters should not feel so fucked up that we can’t do anything anymore,” he said.

Carter also pointed to the energy required to print and ship a bunch of his work.

“To sell one piece of art that I’ve minted versus the energy expenditure and the emissions it takes for me to sell, let’s say 1,000 prints at $20,” he said. “To now shop those to 1,000 different places and for those things to then be transported to 1,000 different homes. Like, maybe they’re comparable, maybe they’re not. I’m not too interested in doing the math at this point.”

Ultimately, Carter thinks there needs to be better access to renewable energy sources and more innovative hardware in the space.

“And the production of creating that innovative hardware also has to be coming from renewable energy sources, like the entire framework should be working to be carbon negative,” he said. “As carbon neutral to carbon negative as possible. And not just the minting side but the mining side. And, you know, the manufacturing side. It’s a cyclical issue.”

]]>