TechCrunch

TechCrunch

Our guide to setting up a professional-looking home webcam solution with lighting, audio and all the other fixins is here, but getting your DSLR or mirrorless camera hooked up to your computer isn’t as simple as it ought to be.

Now, you could spend $100 or so to get a capture card or dongle that converts your camera’s signal to HDMI, and be done with it. But if you want to be up and running a few minutes from now, here are the software-only solutions for your camera and OS — if any.

Surprisingly, you can’t just take a camera released in the last couple years and plug it into your computer and expect it to work. So far only Canon, Fujifilm and Panasonic provide free webcam functionality to at least one desktop OS. For Nikon, Sony and Olympus, you may have to pay or put up with a watermark.

Here are the easiest ways to put each brand of camera to work. (Spoiler warning: For Macs, it’s mostly Cascable. I’ll mention that a few more times because people are probably just scrolling past this to their brand.)

Canon: EOS Webcam Utility

Canon released this software just a couple weeks ago and it’s still in beta, so there may be a few hiccups — but it supports both Windows and Apple machines and a good variety of camera bodies. There’s even some extra documentation and tutorials for the app at its microsite.

Canon released this software just a couple weeks ago and it’s still in beta, so there may be a few hiccups — but it supports both Windows and Apple machines and a good variety of camera bodies. There’s even some extra documentation and tutorials for the app at its microsite.

Compatibility is pretty good, working with any of their camera bodies from the last 3-4 years: the Rebel T6-T7i, T100, SL2, SL3, 5D Mk IV, 5DS, 5DS R, 6D Mk II, 7D Mk II, 77D, 80D, 90D, 1D X Mark II and Mark III, M6 Mk II, M50, M200, R, RP, PowerShot G5X Mk II, G7X Mk III and SX70 HS. Download the software here.

If you’re having trouble, check out the third-party apps listed for other brands below and see if you have more luck.

Fujifilm: X Webcam

Fujifilm’s solution is easy, but a bit limited. The popular X100 series is not supported, and Macs are left out in the cold as well. But if you have one of the company’s more recent interchangeable-lens bodies and a Windows 10 machine, you’re golden. Just install and plug in your camera with a normal USB cable.

Compatibility includes the X-T2, X-T3, X-T4, X-Pro2, X-Pro3, X-H1, GFX100, GFX 50R and GFX 50S. Get that medium format setup going right and your eyes will be in focus but not your ears. Download the software here.

For Macs, Cascable is a useful bit of Mac software that acts as a bridge to your camera for a variety of purposes, and the author just added webcam capability. It has wide compatibility for both wired and wireless connections, and provides broader functionality than Fuji’s own software, but it isn’t free. But the current $30 price is probably less than you’d pay if you opted for a nice webcam instead.

If you’re confident fiddling around in command lines, this tutorial tells you how to get a Fuji camera working on Macs with a bit of fiddling around and some other third-party software.

Panasonic: Lumix Tether

Panasonic just made the webcam-capable version of their Lumix Tether Windows app available, and you can tell from the paucity of the documentation that it’s a pretty bare-bones solution. The price is right, though. It works with the GH5, G9, GH5S, S1, S1R and S1H. The company also posted a helpful start-to-finish tutorial on how to get going with streaming software like OBS here:

Cascable works well with a variety of Panasonic cameras, far more than the official app, even some superzooms that could be really fun to play with in this context.

Sony

There’s no official software to turn your Sony cameras into webcams, so if you want a one-stop solution you have to jump straight into third-party options. On Windows, there is a sort of workaround that uses Sony Remote to tether the image and then hijack it into streaming software; this video explains it well. It’s not ideal, but it’s something.

Cascable on Mac is again your best bet there, with support reaching back several generations to cameras like the NEX series and RX100 III. Ecamm Live also has limited Sony compatibility, but only supports the latest bodies. It’s $12 per month, but there’s a free trial if you want to give it a go first.

Olympus

It’s the same story for Olympus on Windows. There’s no official support, but you may be able to use tethering software to collect the live view image and forward that to the streaming software.

On Mac, Cascable has wired support for many more Oly bodies, including Stylus cameras and the retro-style PEN F, which will probably resent being used for such a modern purpose. Ecamm Live has compatibility with the latest bodies — the E-M1 II, III and X, and the E-M5 original and Mk II. No go on the PEN series, unfortunately.

Nikon

Surprisingly, while Nikon recently put up a rather helpful page on streaming using its cameras, it doesn’t produce any of the software itself, referring the reader to a variety of third-party programs.

As before, Cascable seems like the easiest way to get your Nikon working with a Mac, and SparkoCam is a frequent recommendation for Windows.

Warnings to the webcam-curious

These methods may be easy, but they’re not completely without issues.

One potential problem is heat. These cameras were designed primarily for capturing stills and short video clips. Running full time for extended periods can result in the camera getting too hot to function and shutting down. A camera shouldn’t damage itself seriously, but it’s something to be aware of. The best way to avoid this is using a dummy battery with a power adapter — these are pretty easy to find, and will mitigate overheating.

Audio also may not be as nice as the image. For people doing serious video work, an external mic is almost always used, and there’s no reason you shouldn’t do the same. Considering a solid mic can be had for under $50 and should provide a substantial upgrade to your device’s built-in one, there’s no reason not to take the plunge.

You may also want to check a few forums for the best settings to use for the camera, from making sure it doesn’t turn off after a few minutes to exposure choices. For instance, since you’re not doing stills, you don’t need to worry about sharpness, so you can shoot wide open. But then you’ll need to make sure autofocus is working quickly and accurately, or you’ll end up lost in the bokeh. Check around, try a few different setups, and go with what works best in your situation.

And when you’re ready to take the next step, consult our more thorough guide to setting the scene.

]]>

TechCrunch

TechCrunch

But as tired parents juggle work, family and sanity all day, nearly every day, they say edtech is not a remedy for all education gaps right now.

Parents across all income groups are struggling with homeschooling.

“Our mental health is like whack-a-mole,” said Lisa Walker, the vice president of brand and corporate marketing at Fuze. Walker, who lives in Boston but has relocated to Vermont for the pandemic, has two kids, ages 10 and 13. “One person is having a good day. One person is having a bad day, and we’re just going throughout the family to see who needs help.”

Socioeconomically disadvantaged families have it even worse because resources are strapped and parents often have to work multiple jobs to afford food to put on the table.

One major issue for parents is balancing a decrease in live learning with an uptick in “do it at your own pace” learning.

Walker says she is frustrated by the limited amount of live interaction that her 10-year-old has with teachers and classmates each day. Once the one hour of live learning is done, the rest of the school day looks like him sitting in front of a computer. Think pre-recorded videos, followed up by an online quiz, capped with doing homework on a Google doc.

Asynchronous learning is complicated because, while it is not interactive, it is more inclusive of all socioeconomic backgrounds, Walker said. If all learning material is pre-recorded, households that have more kids than computers are less stressed to make the 8 a.m. science class, and can fit in lessons by taking turns.

“Even though I know there’s a lot of video fatigue out there, I would love there to be more live learning,” Walker said. “Tech is both part of the problem and part of the solution.”

TraLiza King, a single mother living in Atlanta who works full time as a senior tax manager for PWC, points out the downside of live video instruction when it comes to working with younger children.

One challenge is overseeing her four-year-old’s Zoom calls. King needs to be available to help her daughter, Zoe, use the platform, which isn’t intuitive for kids at that age. She helps Zoe log on and off and mute when appropriate so instruction can go on interrupted, ironically enough.

Her 18-year-old college freshman could supervise the four-year-old’s learning, but King doesn’t want her older daughter to feel responsible for teaching. It leaves King to play the role of Zoom tech support, and teacher, in addition to mom and full-time employee.

“This has been a double-edged sword; there’s beauty in it that I get to see what my girls are learning and be a part of their everyday,” she said. “But I am not a preschool teacher.”

Some parents are finding success in pretending it is business as normal. The moment that Roger Roman, the founder of Los Angeles-based Rythm Labs, and his wife saw that there was a shutdown, they scrambled to create a schedule for the children. Breakfast at 6 a.m., physical education right after, and then workbook time and homework time. If their five-year-old checks all the boxes, he can “earn” 30 minutes of screen time.

The Roman family’s schedule for their child.

Technology definitely helps. Roman says he relies on a few apps like Khan Academy Kids and Leapfrog to give him some time to take work calls or meetings. But he says those have been more like supplements instead of replacements. In fact, he says one big solution he found is a bit more low-tech.

“Printers have been a godsend,” he said

The kids being at home has also given the Roman family an opportunity to address the racial violence and police brutality in our country. The existing school curriculums around history have been scrutinized for lacking a comprehensive and accurate account of slavery and Black leaders. Now, with parents at home, those disparities are even more clear. Depending on the household, the gaps around education on slavery can either inspire a difficult conversation on inequality in the country, or leave the talk tabled for schools to reopen.

Roman says he doesn’t remember a time where he wasn’t aware of racism and injustice, and assumes the same will be true for his sons.

“The murders of Ahmaud, Breonna, and George have forced my wife and me to be brutally honest with my five-year-old about this country’s long, dark history of white supremacy and racial oppression,” he said. “We didn’t expect to have these discussions so soon with him, but he’s had a lot of questions about the images he’s been seeing, and we’ve confronted them head-on.”

Roman used books to help illustrate racism to his sons. Edtech platforms have largely been silent on how they’re addressing anti-racism in their platforms, but Quizlet says it is “pulling together programming that can make a real impact.”

What’s next for remote learning?

In light of the struggles parents and educators alike are seeing with the current set of online learning tools and their inability to inspire young learners, new edtech startups are thinking about how the future of remote learning might look.

Zak Ringelstein, the co-founder of Zigazoo, is launching a platform he describes as a “TikTok for kids.” The app is for children from preschool to middle school, and invites users to post short-form videos in response to project-based prompts. Exercises could look like science experiments — like building a baking soda volcano or recreating the solar system from household items — and the app is controlled by parents.

The first users are Ringlestein’s kids. He says they became disengaged with learning when it was just blind staring at screens, leading him to conclude that interaction is key. Down the road, Zigazoo plans to forge partnerships with entertainment companies to have characters act as “brand ambassadors” and feature in the short-form video content. Think “Sesame Street” characters starting a TikTok trend to help kids learn what photosynthesis is all about.

A preview of Zigazoo, a “TikTok for kids” and its video-based prompts“As an educator, I’ve been surprised at how little content exists for parents that is not just entertaining but is actually educational,” he said.

Lingumi is a platform that teaches toddlers critical skills, like learning English. The company began because preschool classes are packed with so many students that teachers can’t give one on one feedback during the “sponge-like years.” Lingumi uses another startup, SoapBox, and its voice tech to listen and understand children, assess how they are pronouncing words and judge fluency.

“Edtech products were designed to work in the classroom and a teacher was supposed to be in the mix somewhere,” said Dr. Patricia Scanlon, the CEO of SoapBox. “Now, the teacher can’t be with the kids individually and this is a technology that gives updates on children’s progress.”

Another app, Make Music Count, was started by Marcus Blackwell to help students use a digital keyboard to solve math equations. It serves 50,000 students in more than 200 schools, and recently landed a partnership with Cartoon Network and Motown records to use content as lessons for followers. If you log onto the app, you are presented with a math problem that, once solved, tells you which key to play. Once you solve all the math problems in the set, the keys you played line up to play popular songs from artists like Ariana Grande and Rihanna.

The app is using a well-known strategy called gamification to engage its younger users. Gamification of learning has long been effective in engaging and contextualizing studies for students, especially younger ones. Add a sense of accomplishment, like a song or a final product, and kids get the positive feedback they’re looking for. The strategy is found in the underpinnings of some of the most successful education companies we see today, from Quizlet to Duolingo.

But in Make Music Count’s case, it’s forgoing gamification’s usual trappings, like points, badges and other in-app rewards to instead deliver something far more fun than virtual items: music that kids enjoy and often seek out on their own.

Gamification, much like technology more broadly, is not all-encompassing of the deeply personal and hands-on aspects of school. Yet that is what parents need right now. We’re left with a reminder that technology can only help so much in a remote-only world, and that education has always been more than just comprehension and test-taking.

The missing piece to edtech: School isn’t just learning, it’s childcare

At the end of the day, if the future of work is remote, parents will need more support with childcare assistants. Some startups trying to help that include Cleo, a parenting benefits startup that recently partnered with on-demand childcare service UrbanSitter.

“As working moms desperate for a solution to the crisis facing parents today, we were focused on developing a solution that didn’t just work for our members and enterprise clients, but also one that we’d use ourselves. After experimenting and trying everything from virtual care to scheduling shifts to looking for new caregivers ourselves, we realized the only solution that would work for families would require a new model of childcare designed for the unique issues COVID-19 has created,” Cleo CEO Sarahjane Sacchetti told TechCrunch in May.

Sara Mauskopf, the co-founder of childcare marketplace Winnie, said that tech companies trying to help remote learning need to remember that “it’s not just the education aspect that has to be solved for.”

“School is a form of childcare,” she said.

“The thing that irks me is that I see these tweets all the time that ‘more people are going to homeschool than ever before,” Mauskopf said. “But no one is going to feed my toddler mac and cheese or change their diaper.”

]]>

TechCrunch

TechCrunch

TechCrunch covered a part of the insurtech world earlier this year, asking why insurance marketplaces were picking up so much investment, so quickly. Lemonade is different from insurance marketplaces in that it’s a full-service insurance provider.

Indeed, as its S-1 notes:

By leveraging technology, data, artificial intelligence, contemporary design, and behavioral economics, we believe we are making insurance more delightful, more affordable, more precise, and more socially impactful. To that end, we have built a vertically-integrated company with wholly-owned insurance carriers in the United States and Europe, and the full technology stack to power them.

Lemonade is pitching that it has technology to make insurance a better business and a better consumer product. It is tempting. Insurance is hardly anyone’s favorite product. If it could suck marginally less, that would be great. Doubly so if Lemonade could generate material net income in the process.

Looking at the numbers, the pitch is a bit forward-looking.

Parsing Lemonade’s IPO filing, the business shows that while it can generate some margin from insurance, it is still miles from being able to pay for its own operation. The filing reminds us more of Vroom’s similarly unprofitable offering than Zoom’s surprisingly profitable debut.

The numbers

Lemonade is targeting a $100 million IPO according to its filings. That number is imprecise, but directionally useful. What the placeholder target tells us is that the company is more likely to try to raise $100 million to $300 million in its debut than it is to take aim at $500 million or more.

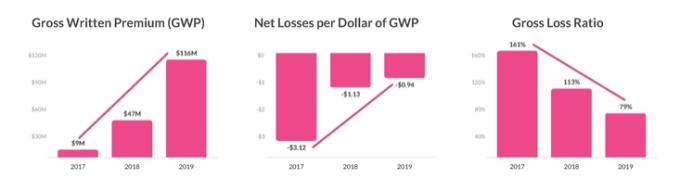

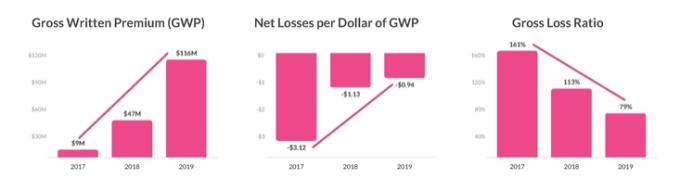

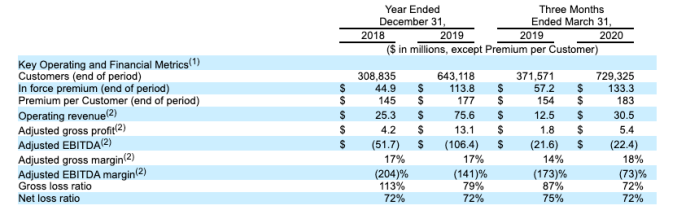

So, the company, backed by $480 million in private capital to date, is looking to extend its fundraising record, not double it in a single go. What has all that money bought Lemonade? Improving results, if stiff losses. Let’s parse some charts that the company has proffered and then chew on its raw results.

First, this trio of bar charts that are up top in the filing:

Gross written premiums (GWP) is the total amount of revenue expected by Lemonade for its sold insurance products, notably discounting commissions and some other costs. As you’d expect, the numbers are going up over time, implying that Lemonade was effective in selling more insurance products as it aged.

The second chart details how much money the company is losing on a net basis compared to the firm’s gross written premium result. This is a faff metric, and one that isn’t too encouraging; Lemonade’s GWP more than doubled from 2018 to 2019, but the firm’s net losses per dollar of GWP fell far less. This implies less-than-stellar operating leverage.

The final chart is more encouraging. In 2017 the company was paying out far more in claims than it took in from premiums. By 2019 it was generating margin from its insurance products. The trend line here is also nice, in that the 2018 to 2019 improvement was steep.

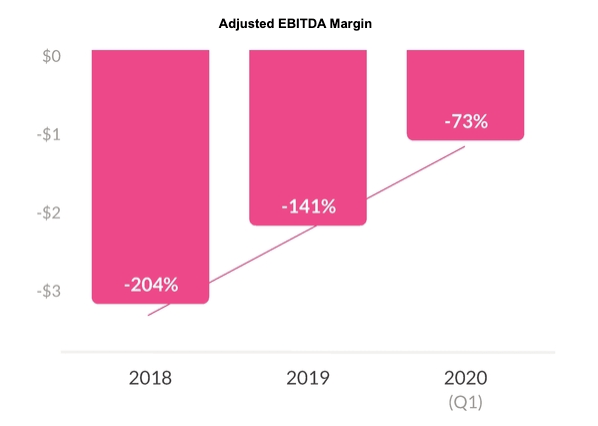

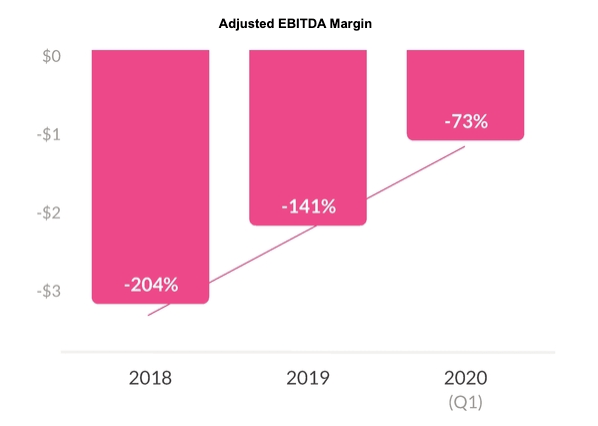

And then there’s this one:

This looks good. That said, improving adjusted EBITDA margins that remain starkly negative as something to be proud of is very Unicorn Era. But 2020 is alive with animal spirits, so perhaps this will engender some public investor adulation.

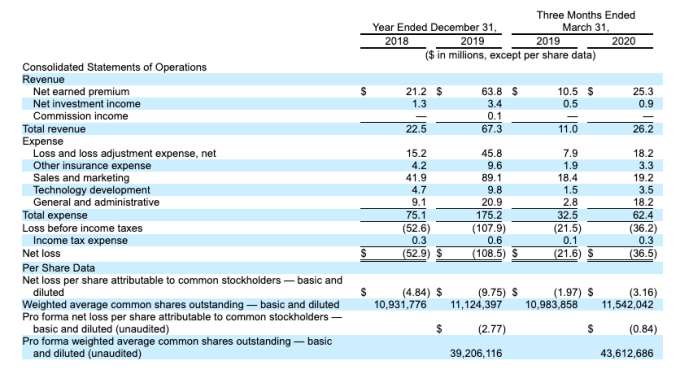

Regardless, let’s dig into the numbers. Here’s the main income statement:

Some definitions. What is net earned premium? According to the company it is “the earned portion of our gross written premium, less the earned portion that is ceded to third-party reinsurers under our reinsurance agreements.” Like pre-sold software revenue, premium revenue is “earned pro rata over the term of the policy, which is generally.” Cool.

Net investment income is “interest earned from fixed maturity securities, short term securities and other investments.” Cool.

The two numbers are the company’s only material revenue sources. And they sum to lots of growth. From $22.5 million in 2018 to $67.3 million in 2019, a gain of 199.1%. More recently, the company’s Q1 results saw its revenue grow from $11.0 million in 2019 to $26.2 million in 2020, a gain of 138.2%. A slower pace, yes, but from a higher base and more than large enough for the company to flaunt growth to a yield-starved public market.

Now, let’s talk losses.

Deficits

We’ll talk margins a little later, as that bit is annoying. What matters is that Lemonade’s cost structure is suffocating when compared to its ability to pay for it. Net losses rose from $52.9 million in 2018 to $108.5 million in 2019. More recently, a Q1 2019 net loss of $21.6 million was smashed in the first quarter of 2020 when the firm lost $36.5 million.

Indeed, Lemonade only appears to lose more money as time goes along. So how is the company turning so much growth into such huge losses? Here’s a hint:

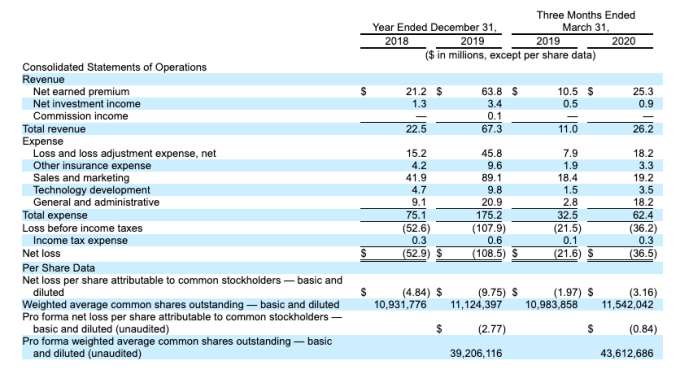

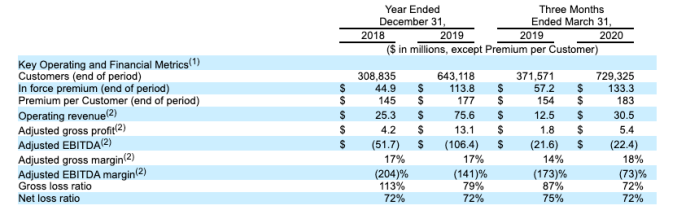

This is messy, but we can get through it. First, see how operating revenue is different than the GAAP revenue metrics we saw before? That’s because it’s a non-GAAP (adjusted) number that means the “total revenue before adding net investment income and before subtracting earned premium ceded to reinsurers.” Cool.

That curiosity aside, what we really care about is the company’s adjusted gross profit. This metric, defined as “total revenue excluding net investment income and less other costs of sales, including net loss and loss adjustment expense, the amortization of deferred acquisition costs and credit card processing fees,” which means gross profit but super not really, is irksome. Given that Lemonade is already adjusting it, it’s notable that the company only managed to generate $5.4 million of the stuff in Q1.

Recall that the company had GAAP revenue of $26.2 million in that three-month period. So, if we adjust the firm’s gross profit, the company winds up with a gross margin of just a hair over 20%.

So what? The company is spending heavily — $19.2 million in Q1 alone — on sales and marketing to generate relatively low-margin revenue. Or more precisely, Lemonade generated enough adjusted gross profit in Q1 2020 to cover 28% of its GAAP sales and marketing spend for the same period. Figure that one out.

Anyway, the company raised $300 million from SoftBank last year, so it has lots of cash. “$304.0 million in cash and short-term investments,” as of the end of Q1 2020, in fact. So, the company can sustain its Q1 2020 operating cash burn ($19.4 million) for a long time. Why go public then?

Because like we wrote this morning (Extra Crunch subscription required), Vroom showed that the IPO market is open for growth shares and SoftBank needs a win. Let’s see what investors think, but this IPO feels like it’s timed to get out while the getting is good. Who can get mad at that?

]]>