TechCrunch

TechCrunch

REEF began its life as Miami-based ParkJockey, providing hardware, software and management services for parking lots. It has since expanded its vision while remaining true to its basic business model. While it still manages parking lots, it now it adds infrastructure for cloud kitchens, healthcare clinics, logistics and last-mile delivery, and even old school brick and mortar retail and experiential consumer spaces on top of those now-empty parking structures and spaces.

Like WeWork, REEF leases most of the real estate it operates and upgrades it before leasing it to other occupants (or using the spaces itself). Unlike WeWork, the business actually has a fair shot at working out — especially given business trends that have accelerated in response to the health and safety measures implemented to stop the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In part that’s because REEF does operate its own businesses on the premises and works with startups to provide actual goods and services that are location dependent for their success and revenue generating.

The money will be used to scale from its roughly 4,800 locations to 10,000 new locations around the country and to transform the parking lots into “neighborhood hubs,” according to Ari Ojalvo, the company’s co-founder and chief executive.

SoftBank and Mubadala are joining private equity and financial investment giants Oaktree, UBS Asset Management and the European venture capital firm Target Global in providing the cash for the massive equity financing. Meanwhile, REEF Technology and Oaktree are collaborating on a $300 million real estate investment vehicle, the Neighborhood Property Group, as Bloomberg reported on Monday.

In all, REEF, which could reasonably be described as a WeWork for the neighborhood store, has $1 billion in capital coming to build out what it calls a proximity-as-a-service platform.

Since taking a minority investment from SoftBank back in 2018 (an investment which reportedly valued the company at $1 billion) and transforming from ParkJockey into REEF Technology, the company added a booming cloud kitchen business to support the increase in virtual restaurant chains.

In addition, it added a number of service providers as partners, including last-mile delivery startup Bond (and the logistics giant, DHL); the national primary healthcare services clinic operator and technology developer, Carbon Health; the electric vehicle charging and maintenance provider, Get Charged; and — at its operations in London — the new vertical farm developer, Crate to Plate (Ojalvo said it was in talks with the established vertical farming companies in the U.S. on potential partnerships).

Next year, the company plans to launch the first of its experiential, open-air entertainment venues at a space it operates in Austin, according to Ojalvo.

And further down the road, the company sees an opportunity to serve as a hub for the kinds of data-processing centers and telecommunications gateways that will power the smart city of the 21st century, Ojalvo said.

“We have inbound interest from companies that do edge computing and companies getting ready with 5G,” he said. “Data and infrastructure is a big part of our neighborhood hub. It’s like electricity. Without electricity and connectivity, we don’t have the world we want to see.”

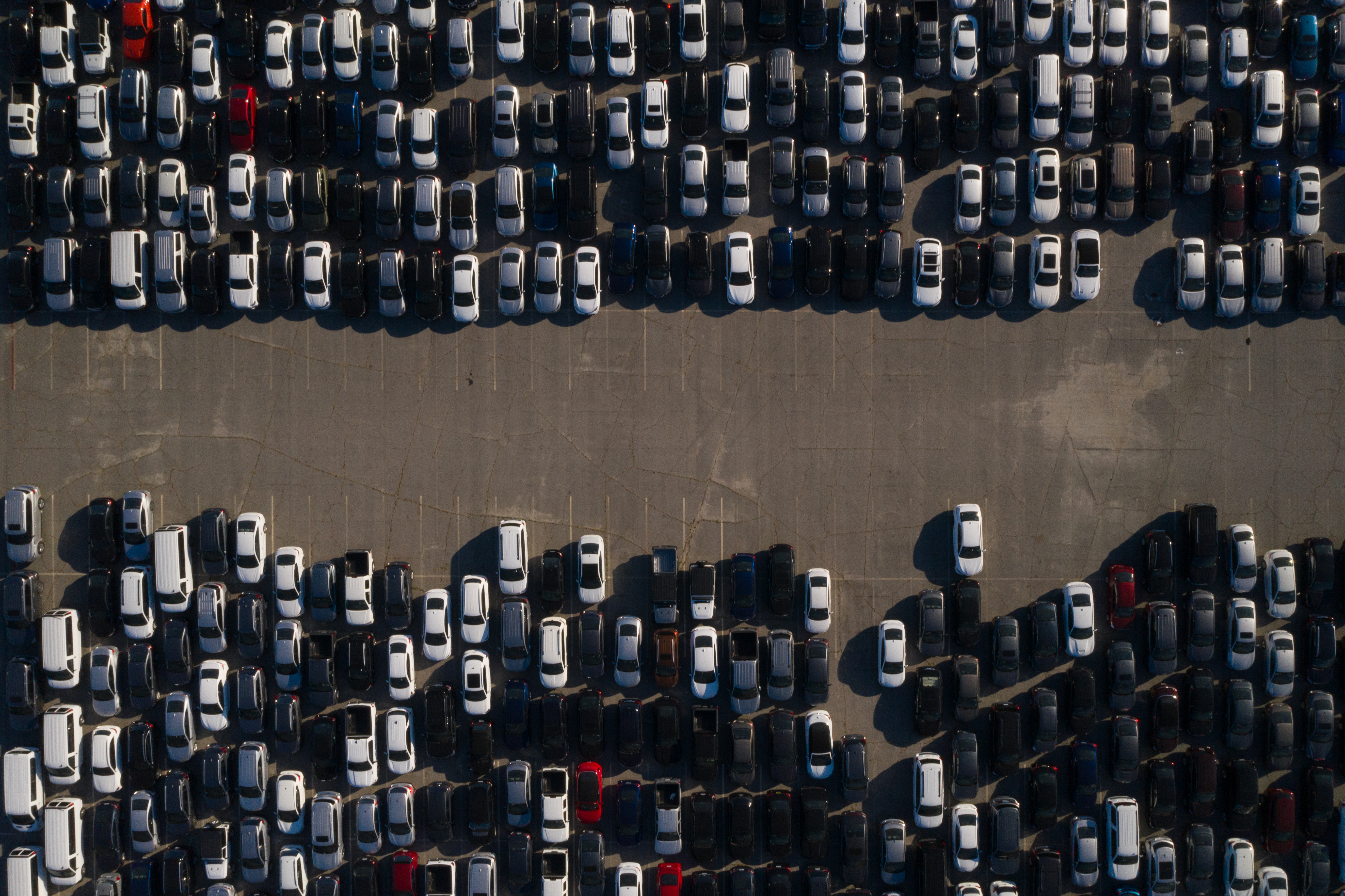

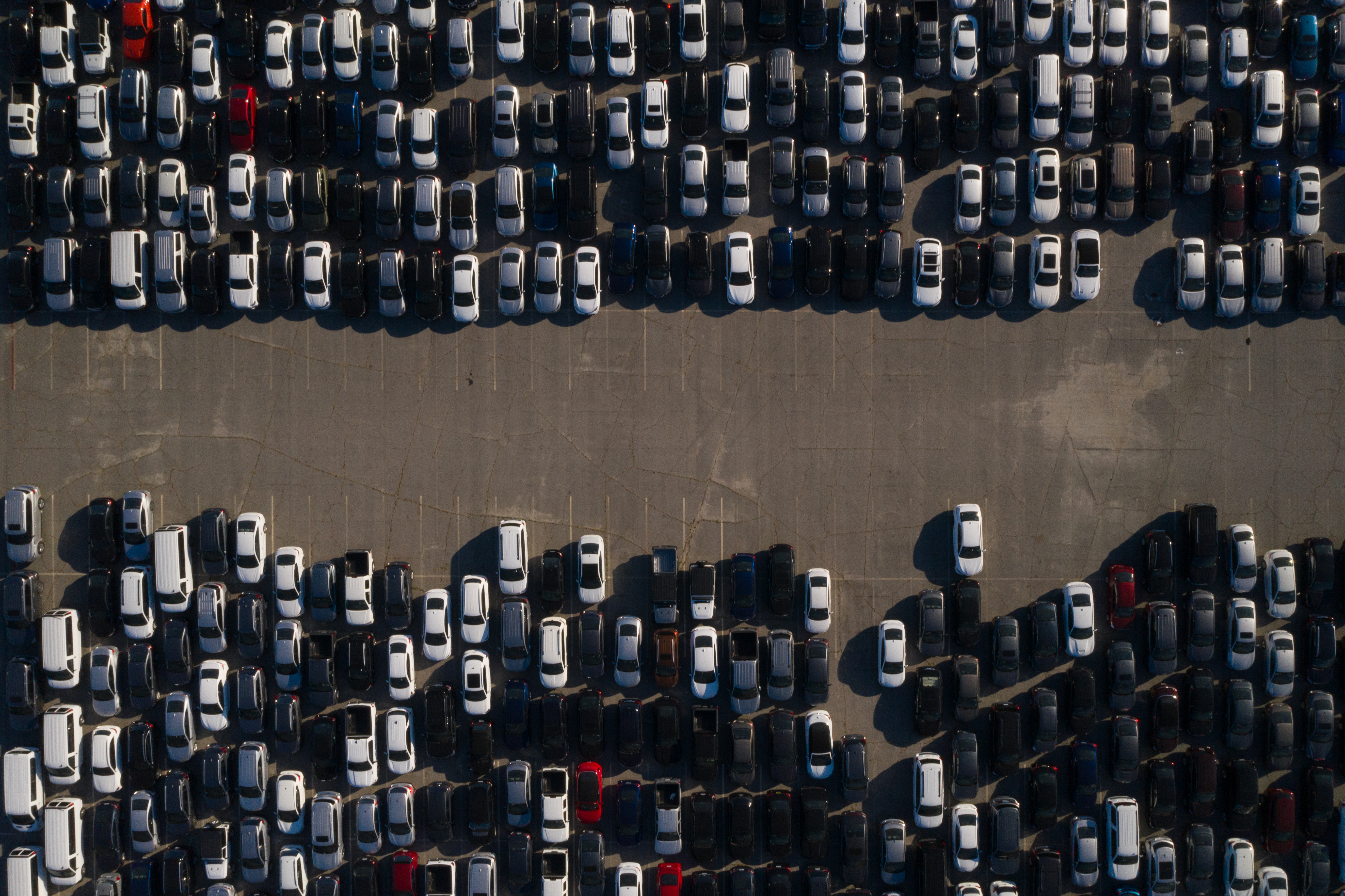

Rental cars are stored in a parking lot at Dodger Stadium in this aerial photograph taken over Los Angeles, California, U.S., on Wednesday, May 27, 2020. Hertz Global Holdings Inc. will sell as many of its rental cars as possible while in bankruptcy to bring its huge fleet in line with reduced future demand in a post-pandemic economy.

The bulk of the company’s revenue is coming from its parking business, but Ojalvo expects that to change as the its cloud kitchen business continues to grow. “Neighborhood Kitchens will be a significant part of non-parking revenue,” said Ojalvo.

REEF already operates more than 100 Neighborhood Kitchens across more than 20 markets in North America, and that number will only grow as the company expands its regional footprint. It’s hosting virtual kitchens from celebrity chefs like David Chang’s Fuku, and, according to the company, offering lifelines to beloved local restaurateurs like the chain Jack’s Wife Freda in New York or Michelle Bernstein’s kitchens in Miami.

These restaurants are, in some cases, taking advantage of the employees that REEF Technology has operating its network of kitchens. It’s another difference between WeWork and REEF. The company not only provides the space, in many instances it’s providing the labor that’s allowing businesses to scale.

The company already employs over a thousand kitchen workers prepping food at its restaurants. And REEF acquired a company earlier in May to consolidate its back-end service for on-demand deliveries.

That same strategy will likely apply to other aspects of the company’s services, as well.

“We’re building a platform of proximity,” says Ojalvo. “That proximity is driven through an install base that’s in parking lots or parking garages… [and] that enables all sorts of companies to use its proximity as a platform. To basically build their marketplaces.”

CARDIFF, UNITED KINGDOM – DECEMBER 22: A Deliveroo rider at work at night on December 22, 2018 in Cardiff, United Kingdom. (Photo by Matthew Horwood/Getty Images)

As REEF raises money for expansion, it’s tapping into a new theory of urban development embraced by mayors from Amsterdam to Tempe, Ariz. calling for a 15-minute city (one where the amenities needed for a comfortable urban existence are no more than 15 minutes away).

It’s a worthwhile goal, but while mayors seem to place the emphasis on the availability of accessible amenities, REEF’s leadership acknowledges that only a few of its parking lots and garages will be multi-use and accessible to neighborhood residents. According to a spokesman, only several hundred of the company’s planned 10,000 businesses will have the kind of multi-use mall environment that encourages neighborhood access. Instead, its business seems to be based on the notion that most delivery services should be no more than 15 minutes away.

It’s a different project, but it also has a number of supporters. One could argue that cloud kitchen providers like Zuul, Kitchen United, and Travis Kalanick’s Cloud Kitchens all ascribe to the same belief. Kalanick, the Uber co-founder and former CEO whose company received billions from SoftBank, has been snapping up properties in the US and Asia under an investment vehicle called City Storage Systems, which also uses parking lots and abandoned malls as fulfillment centers.

Big retailers also have taken notice of the new revenue stream and one of America’s largest, Kroger, is even running a ghost kitchen experiment in the Midwest.

If that’s not enough, there are plenty of under-utilized assets that are already on the market thanks to the economic downturn wrought by the COVID-19 pandemic and the government’s efforts to contain it.

“I guess a lot depends on how you think delivery players work out in the coming years versus say drive through or curbside pickup which seems to be where large national players are focused (Starbucks, McDonalds, Dominos, etc),” wrote on venture investor in an email. “But how do delivery players use these spaces versus say lots of low cost retail spaces that can be used to staging or package returns. Maybe there is a play to add modular or prefab units to the existing parking spaces on provide flex for scaling, but it’s not clear that anyone is growing at a frantic pace… I’m just not sure how to see converted parking versus other… commercial spaces for retail or office that are all searching for new applications.”

The COVID-19 outbreak that has changed so much of modern life in America so quickly in the span of a single year didn’t create the urge to transform the urban environment, but it did much to accelerate it.

As REEF acknowledges, cities are the future.

Roughly two-thirds of the world’s population will live in cities by 2050, and the world’s largest cities are cracking under the pressures of economic, civil, and environmental transformations that they have not been able to address effectively.

Mobility and, by extension, places to store and maintain those mobile technologies are part of the problem. Roughly half of the average modern American city, as REEF notes, is devoted to parking, while parks occupy only 10% of urban spaces. REEF’s language is centered on changing a world of parking lots into a space of paradises, but that language belies a reality that makes its money (at least for now) off of isolating individuals into personal spaces where their commercial needs are met by delivery — not by community interaction.

Still, the fact remains that something needs to change.

“Traditional developers and local policies have been slow to adopt new technologies and operating models,” said Stonly Baptiste, an investor in the transformation of urban environments through the fund, Urban.Us (which is not a backer of REEF). “But the demand is growing for a better ‘city product’, the need to make cities better for the environment and our lives has never been greater, and the dream to build the city of the future never dies. Not that dream is subsidized by VC.”

]]>

TechCrunch

TechCrunch

Fewer than 300 pages, the book parachutes the reader immediately into a cab journey in Ireland that Boden is taking post-financial crisis, when bankers weren’t exactly close to the public’s heart. Everything had changed. Yet, concludes the future Starling founder, the big banks had learned nothing and were determined to continue with business as usual. Thus, the scene is set for why a woman in her fifties would be ambitious enough to start a bank of her own.

I wouldn’t characterize Boden’s story as a page-turner in its entirety, but from then on in there’s more than enough narrative drive to get any fintech aficionado to where they want to go, including an account of Boden’s split with former Starling CTO Tom Blomfield, who left with other early members of the management and engineering team to found rival challenger bank Monzo.

As someone who has had the pleasure of speaking to and spending time with a number of people on both sides who were there when the alleged “coup” took place, this section made for uncomfortable reading. And, of course, it’s worth remembering that Boden’s book shares just one side — her side — of the story, which she has every right to own. However, we are yet to get Blomfield’s version of events directly (and may never), while others who were there have already reportedly disputed Boden’s account following the publication of an abbreviated extract in the Sunday Times two weekends ago.

Although the book presented very few surprises for a journalist who has spent the last five years obsessively covering Europe’s fintech industry, there were still one or two “a ha” moments, not least that Boden’s first contact with Harald McPike, the wealthy hedge fund manager who would go on to back Starling, came via a cold inbound message from a member of McPike’s team.

The Starling founder nearly ignored the message completely, but what followed was an offer not just to invest in Starling’s seed round but to do a mega-round released in tranches. This meant that Boden, who had struggled to raise traditional venture capital from VCs in London and beyond, could focus on recruiting a new team and building out the infrastructure required to launch an actual bank.

She paid a high price, giving away a majority stake in the process. As one former Starling employee told me, having diverted from the VC playbook, lower-ranking staff at the challenger bank would sometimes scratch their heads as the money taps kept running without the numerous fundraising rounds typically required. Now we know how.

This is not my memoir, right. You know, people at the end of their career write memoirs. I’m at the beginning.

There is also the £1 million in debt that Boden racked up employing management consultant firms to help her with the bank license application process. The issue of that debt, and who should take responsibility for it, would add further complications and conflict during the founding team’s split amid Starling’s fundraising woes.

What we don’t always get is a tremendous amount of introspection, with Boden telling me that “Banking On It” is not a memoir but a business book, even thought it often reads like one. “This is not my memoir, right. You know, people at the end of their career write memoirs. I’m at the beginning,” she says, in an exclusive interview with TechCrunch.

Boden said she isn’t going to retire any time soon and that Starling isn’t planning to sell to a big bank. Instead, her sights are set on an IPO. “I’ve had a long career, which is full of interesting things. And the next challenge is in front of me,” she says, with Starling aiming to be profitable by Christmas or early next year.

During our conversation, Boden dispelled one media myth (which my own sources confirm): There was never any kind of gagging order or confidentiality agreement prohibiting parties from talking about the Starling-Monzo split. Instead, by both camps, the media were sold a line designed to avoid a “he said, she said” scenario, creating the clear space needed for each bank to develop its own narrative. If everyone involved was free to talk after all, it seems that Boden has grabbed first-mover advantage.

It’s often said that history is written by the victors, but in the Starling-Monzo split story, it’s still not clear which bank will be victorious, while a less emotional assessment points to both upstarts having already won. For the real enemy was never “Anne” nor “Tom,” but an incumbent banking industry that had grown not just too big to fail but too big to listen and respond to a generation of digital-savvy customers who wanted a more modern banking experience. And it’s within this context that, regardless of who chooses next to disclose their account of events, the real Starling-Monzo story is still being written.

Below is a transcript of Boden’s interview with TechCrunch, lightly edited for length and clarity.

TechCrunch: Why publish a memoir, and why now?

Anne Boden: As you know, I’ve already done another book, “The Money Revolution.” I like words and I like being able to write things down and convey ideas. So I suppose I always knew that I would write a book. And I spend a lot of time and get inspiration from listening to audiobooks from other entrepreneurs, reading entrepreneurial books, anything about other people’s experiences, I take that information to try to help me on this journey.

Therefore, I came to the conclusion that I also had something to give. And I really wanted to do my best to put down and describe the journey of being an entrepreneur, the journey of a startup, and it’s not easy. I think that I come across lots of people asking me for advice, so I wanted to do that, I wanted to put it all down into a book about entrepreneurship. And of course, there’s no point in having a book about entrepreneurship, that’s sort of academic, you have to put a lot of your own experience into it.

Why now? Well, you know, Starling is going to be profitable by Christmas. And last year, and the year before, I just didn’t have enough bandwidth to do it. I thought the time was right, where I had enough to say about sharing my experiences.

I think the first thing is, never give up. And I think the lesson is that you’ll have ups and downs in any particular venture, and you have to recover, you have to be resilient.

Somebody asked me, “does this mean Anne is planning to retire?”

This is really putting down on paper where we are at the moment. It’s been written over several years, and I’m hoping to use this to inspire a generation of entrepreneurs. But also quite excited about the next phase of Starling, of fintech, of tech. I’m still excited by technology, I still get the real buzz about what it can do. I’ve been very, very fortunate to work in some interesting places, and do some interesting things, [and] I think the world could really, really change in the next 10 years, and I think that fintech could really be part of it. So I’m excited about the future. And to you maybe interviewing me in five years’ time about the next book, and in 10 years’ time about the next book after that. This is all about really passing on the knowledge to date.

So you’re not planning to sell or to try and sell Starling anytime soon?

No, no. Look, I didn’t do all this to sell out to a big bank. And I’ve got my sights on an IPO. I’d very much like to do that. I’ve been very, very fortunate, I’ve had a long career, which is full of interesting things. And the next challenge is in front of me. And no, this is setting my sights on the next challenge. And there’s lots going on.

At times during the book — aside from perhaps the chapter dedicated to the alleged “coup” — it’s not entirely clear what you want the reader to take away from the book. If you could pick your top three takeaways, be that business lessons or things people might not know about you or your thought process, what would they be?

I think the first thing is, never give up. And I think the lesson is that you’ll have ups and downs in any particular venture, and you have to recover, you have to be resilient. And every single entrepreneur gets a near death experience, and you have to come back from it. It’s all about recovery and resilience and using that for the next phase.

I think the second thing is that you can’t do it on your own, you have to do it with lots of different types of people and different sources of knowledge. I read a lot, whether they are Paul Graham essays or Stanford podcasts. I reached out to lots of different people through this process that helped me along the way, and I think that you have to figure out where those resources are and bring them all together.

And I think the third thing is, you’ve got to change. People talk about the project and the product iterating and pivoting, but you have to add your own personality and your own learnings have to do that as well. Because as an entrepreneur, as a leader, you are part of the product, you have to think, you have to absorb things and you have to evolve. I was mid-fifties when I decided that I was no longer working for a big bank, but I was going to be an entrepreneur with a startup. And that was a huge transition. But we all can do transitions, and we can do transitions throughout our life. And I hope that people take away that from the book.

It’s interesting you say that. I guess one of the aspects in the book that I felt was slightly missing was, I didn’t get a sense of what that transition was for you personally, whether that be in your management style, your understanding of the difference between corporate life and startup life etc. Was that on purpose; you didn’t want to do too much personal development and [instead] stick with the business side of the story?

I think that this is a business book. You know, I was quite surprised that people started calling it a memoir. And it’s doing really well in the memoir section of Amazon at the moment, so I’m quite flattered. But this isn’t a memoir. This is much more of a practical book about, you want to be an entrepreneur, you want to do a startup, you want to build something that’s never been done before. And the ‘me’ part of it all is to illustrate what happens. This is not my memoir, right. You know, people at the end of their career write memoirs. I’m at the beginning.

I think the pivotal moment in the non-memoir memoir is when Harald McPike said I’m not going to do a seed round, I’m going to do three tranches, so like a mega round, based on very specific and well-aligned milestones tied to the banking license application process.

From my understanding, that allowed you to have some breathing space to get to the stage of a licensed bank. Instead, it could have been, especially when you lost the team, that if you’d got a seed round but then had to almost immediately focus again on trying to raise another round, that may have also been the death of Starling. Do you think I’m over-egging the significance of that funding round coming in tranches and being committed up front?

It is very, very unusual. But it was [also] quite unusual for a startup to have so much documentation, to have so much that had been thought through. I’d been working on Starling for two years, I had a lot of information, lots of research, and I really, really understood the business I was going to build, and I hadn’t raised money. So the first money in was Harald McPike’s money, and I was two years into it all. I had an application for a banking license in three boxes, basically stacked up because they only take boxes and physical paper.

Therefore, I could really define what would be in the three stages, I could really define what you’d get for 3 million, what you’d get for 15 million, what you get for 30. So then I just had to hit those milestones. And hitting those milestones is really, really tough. But I had a lot of experience in running really big projects that are costing hundreds of millions, so I knew very well I could hit those deadlines; I could deal with having to hit the deadline by a certain date and releasing the money. So it was a big advantage that I didn’t have to go back out and fundraise. That was an advantage. But it was also an advantage and a disadvantage that I was two years in. If I advise anybody in a startup, it’s raise money early on and try something. It’s much easier to do that than wait two years whilst you have everything ready, and then raise a big round.

]]>